1960

He takes part in the collective exhibition, Before Picasso. After Miró, at New York’s The Solomon R. Guggenheim

Trip to Tokyo.

Fernando Zóbel, Roger Keyes, Arturo Luz and Kumiko Kondo in Tokyo.

Fernando Zóbel, Roger Keyes, Arturo Luz and Kumiko Kondo in Tokyo.

1961He gives a course on Chinese art and another, on Japanese art at Manila’s University of Ateneo. His tremendous generosity and constant support of art are again noticeable on this occasion, when he donates the money he is paid for the course to the university library for the purchase of collections and reproductions of key paintings in the history of art. 31.

In the years elapsing between 1955 and 1960, Zóbel realizes that Spain is an intellectual, sentimental and pictorial synthesis of what he has been seeking all his life. This awareness throws him into a state of endless anxiety about his life as an artist. As he combines this with his work at the family business, he becomes the inevitable victim of an identity crisis, coupled with a deep depression. Although he tries to overcome this by painting frantically, he finally contracts an alarming disease of unknown physical cause. In December of this year, Zóbel dismantles his office at Ayala and, after 10 years of trying to reconcile his artistic life with the life of a businessman, he decides to go and live in Spain and devote his entire life to painting.

1961

Individual exhibition at the Luz Gallery, Manila. The gallery has been opened this year by his friend Arturo Luz and is soon to become the leading gallery in the Philippines. The exhibition is on a large scale and is a huge success. It marks the end of a stage.

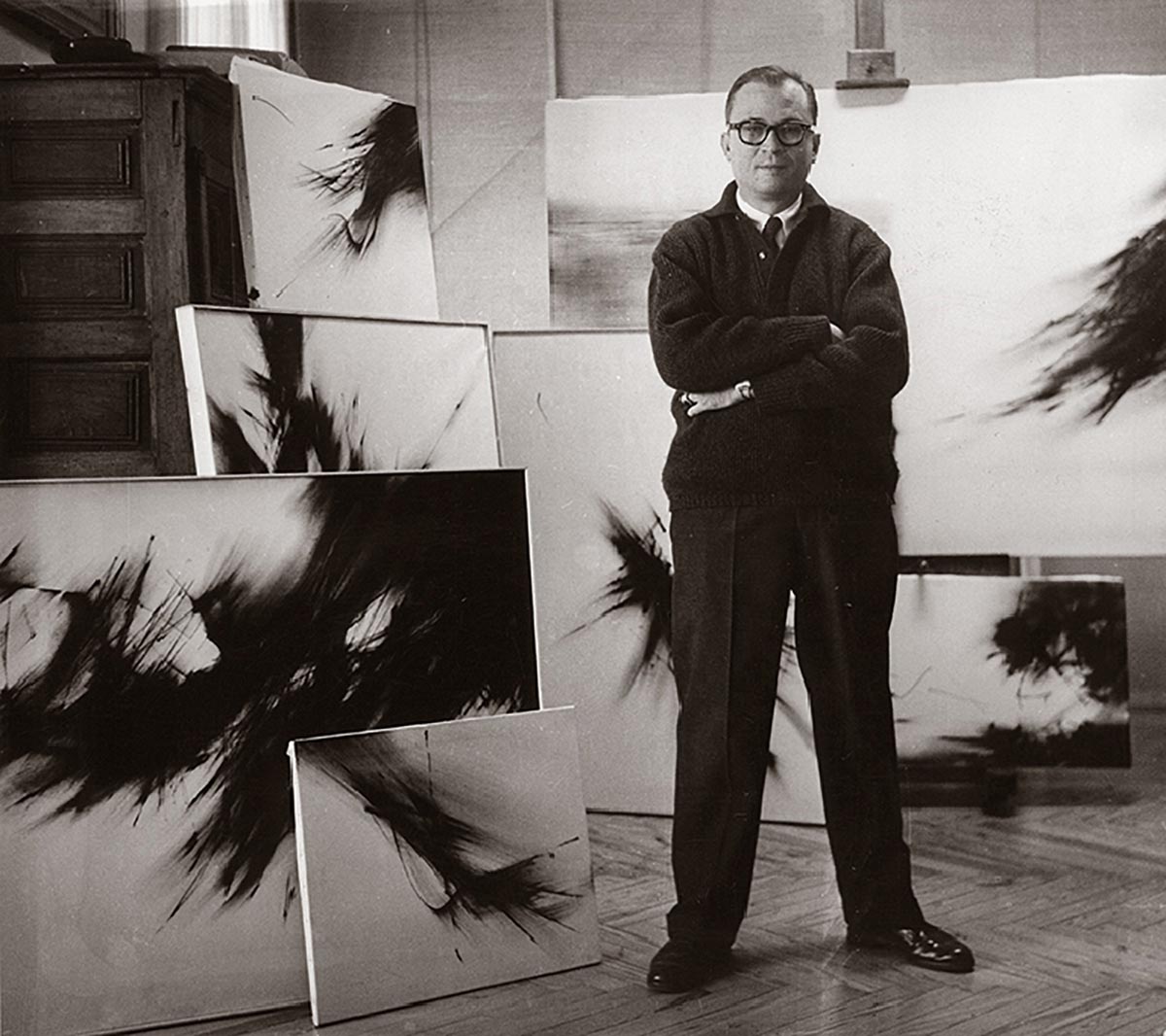

He moves to Madrid for good.

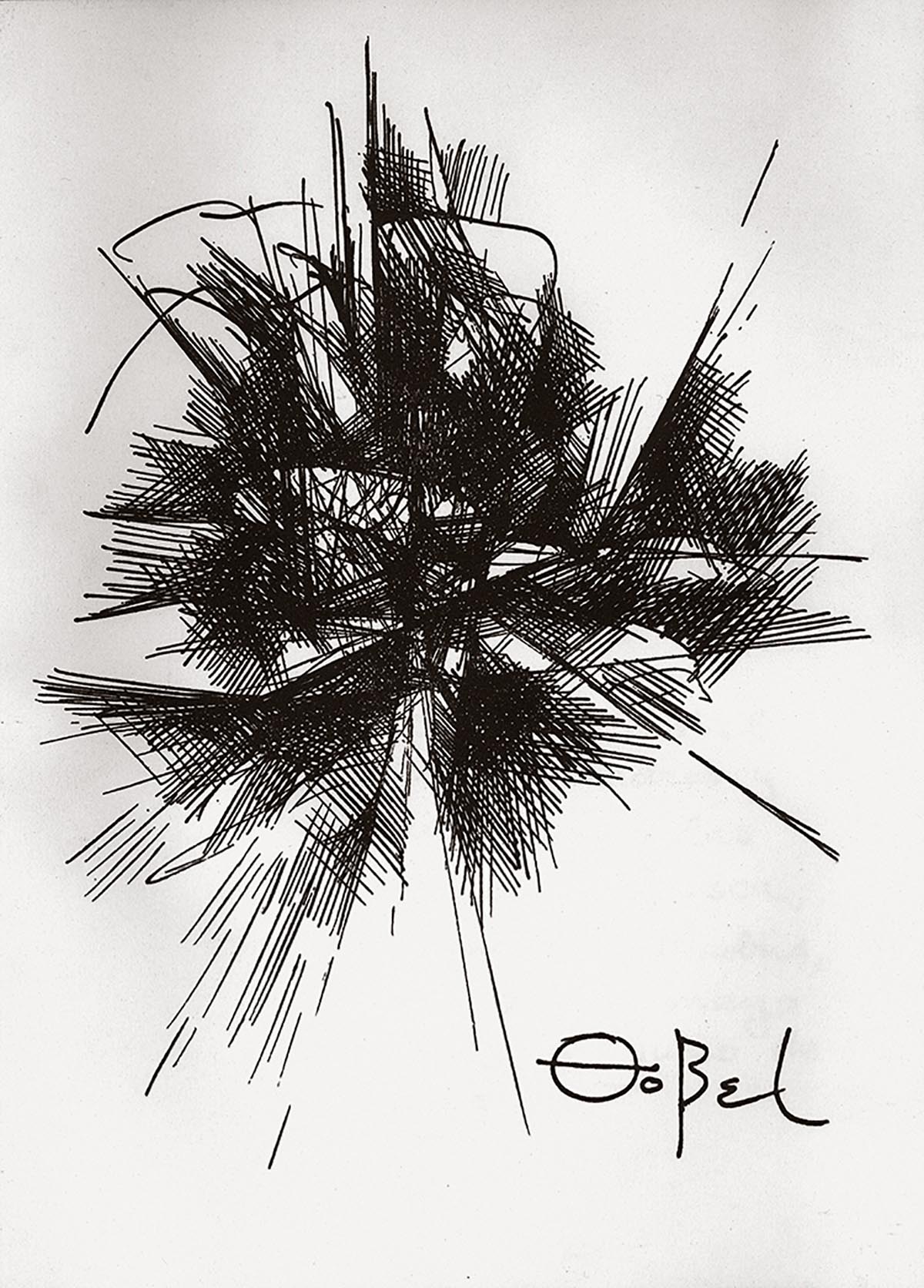

Individual exhibition at Sala Neblí, Madrid. At both exhibitions, he displays pictures from Serie Negra (1959-62), black calligraphies on white. As there is no longer any color, the vibrations caused by the contrast of one or two colors disappear while the artist succeeds in suggesting direction, speed or volume by means of the sweeping strokes of a dry brush across the black calligraphies. As for technique, he avails himself of a syringe, going over the canvas with generous strokes which form angles or deliberately open up on the bare white. This use of black and white leads most of the period’s critics to look on him as an informalist painter. However, unlike other painters such as Saura, Millares or Canogar, Zóbel meditates, observes and studies; he does not trust his hand, the improvised gesture, and such an attitude cannot produce a clamor, a paroxysm or an indictment. Zóbel detaches himself from art informel, as he explains clearly and concisely in a text where he defines his painting in Serie Negra:

Painting of light and line, of movement. Pictures of a swift, improvised execution, like Chinese and Japanese painting. Improvisation permitted by a studied and infinite number of drawings. Line; trajectory. Imprint of movement. Painting without any fuss, without anguish, without any melodramatics. Traditional, yes, but of the ‘other’ Spanish tradition. Of the Velázquez tradition standing in opposition to the Goya tradition (by which no contempt is meant). Of the same Velázquez who attaches as much value to theInfanta as he does to the dress she is wearing and the curtain behind her head. The painter neither gives an opinion nor makes a judgement: he just acts. ‘A statement’. There is gratitude. Awareness of just how much painting has been done. Abstract, to be more precise. Perhaps out of modesty. And out of a lack of interest in foodstuffs. And through attaching too much value to things, which isn’t the same as attaching value to the way they look. Privacy. The armchair by Matisse that so shocked the Russians. Court painting? In any event, a smile. And he’s not always ironic. And why not?” 32

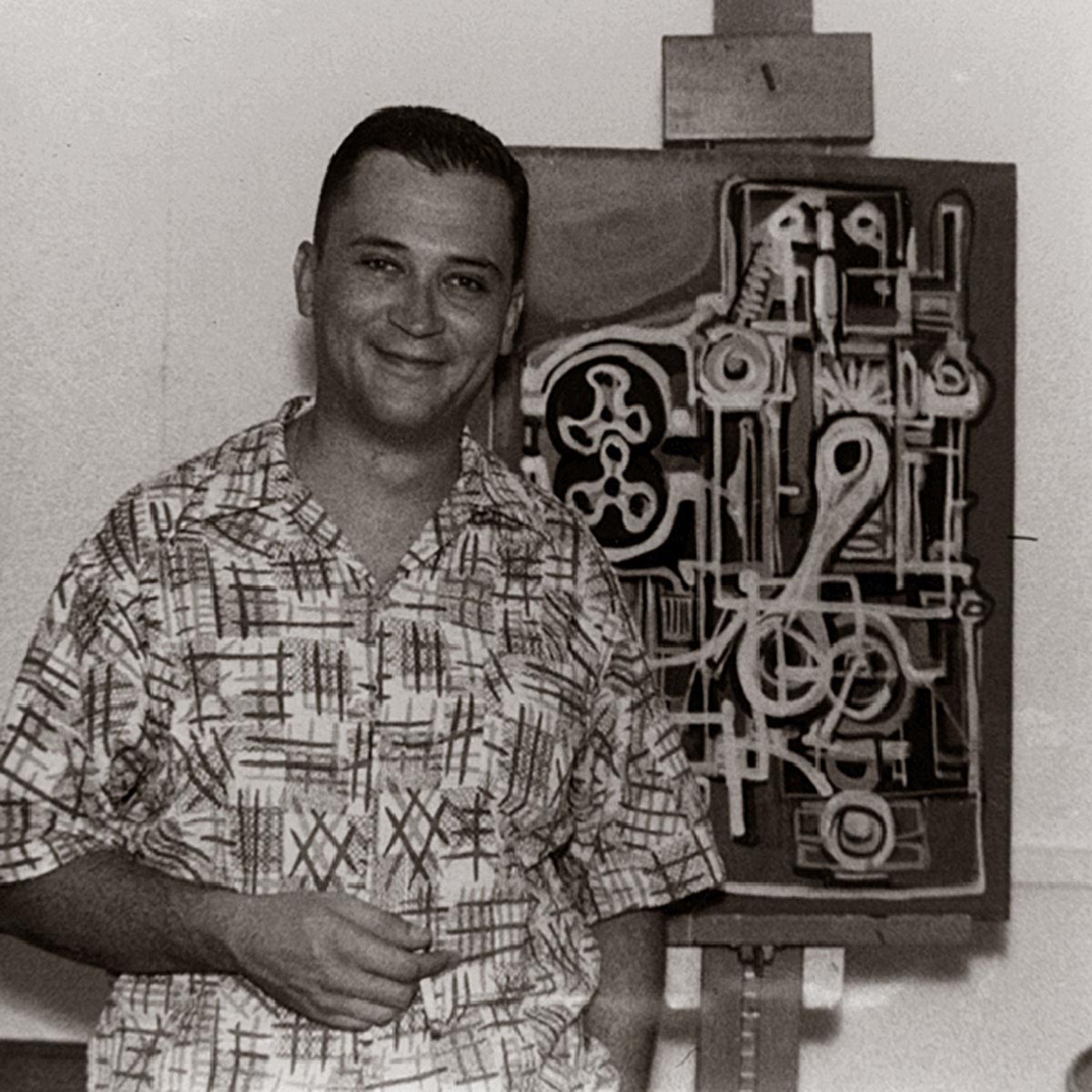

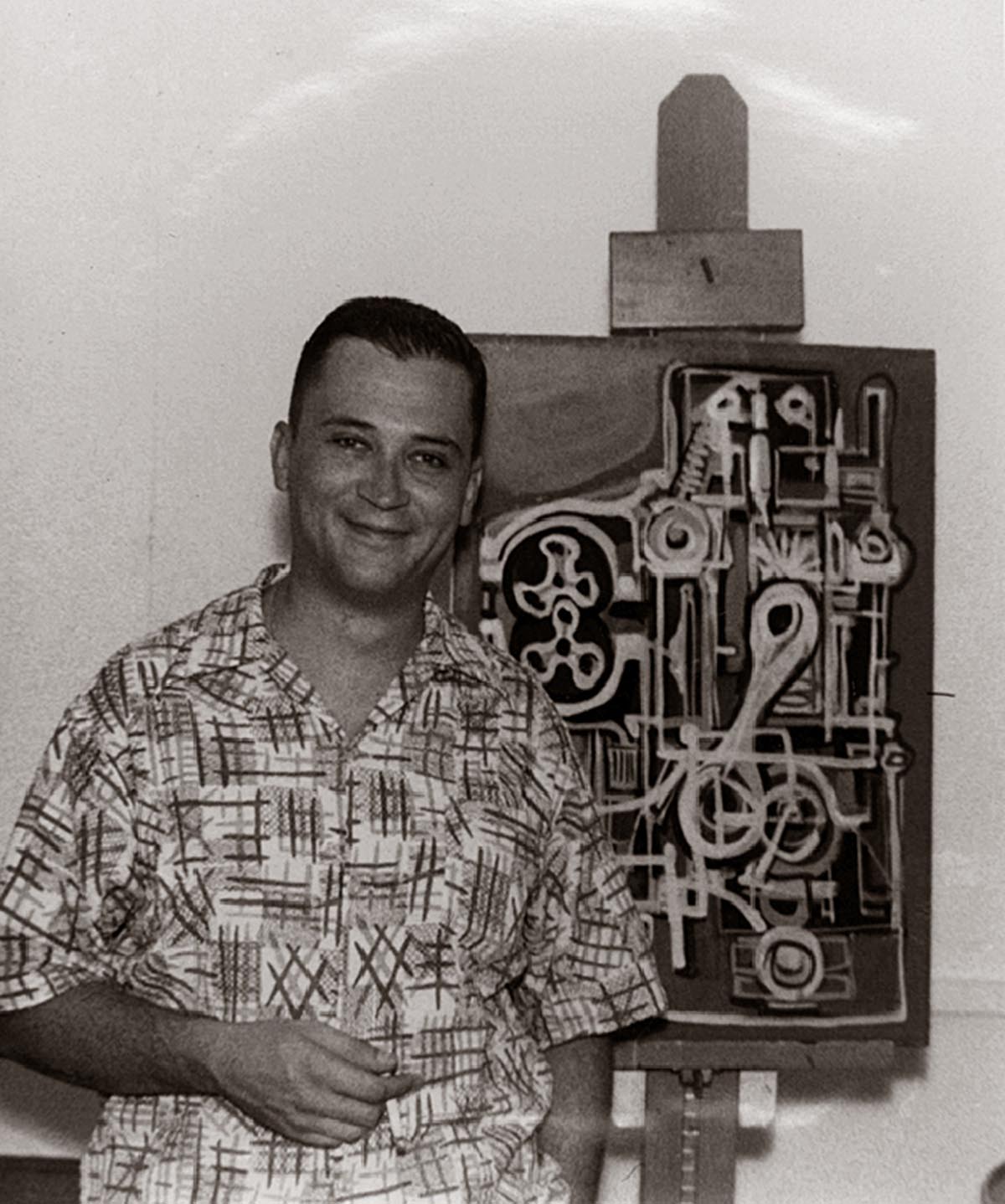

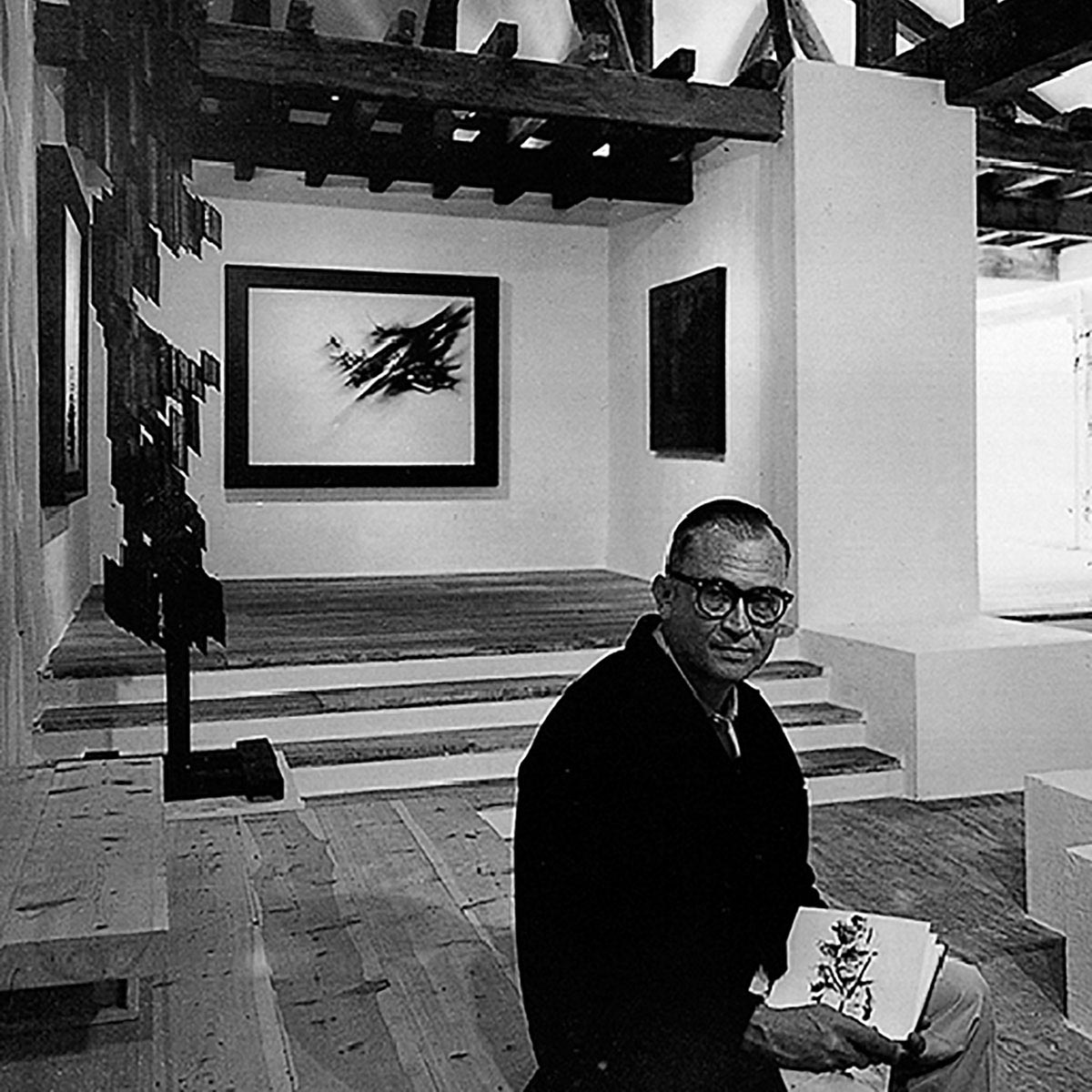

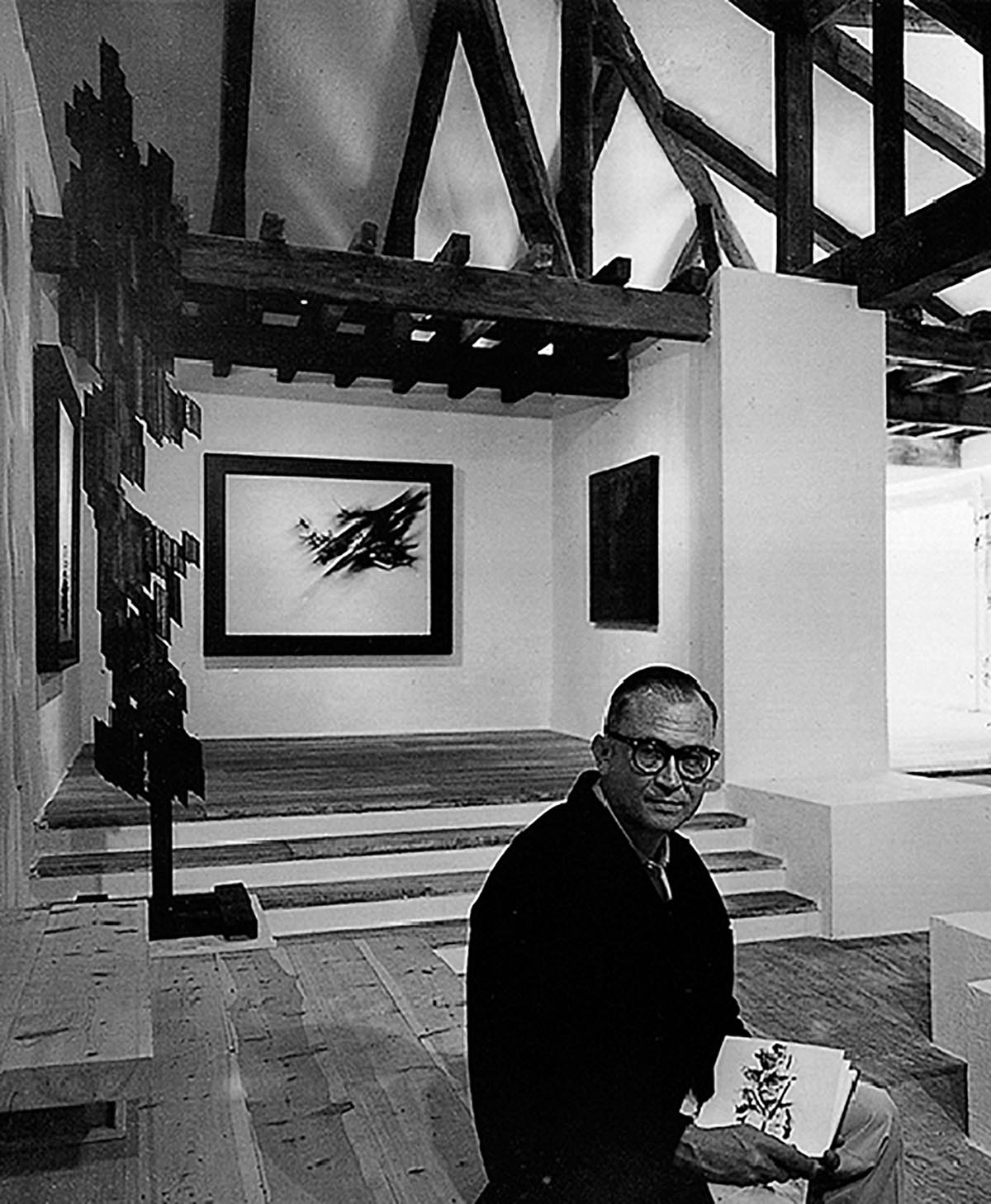

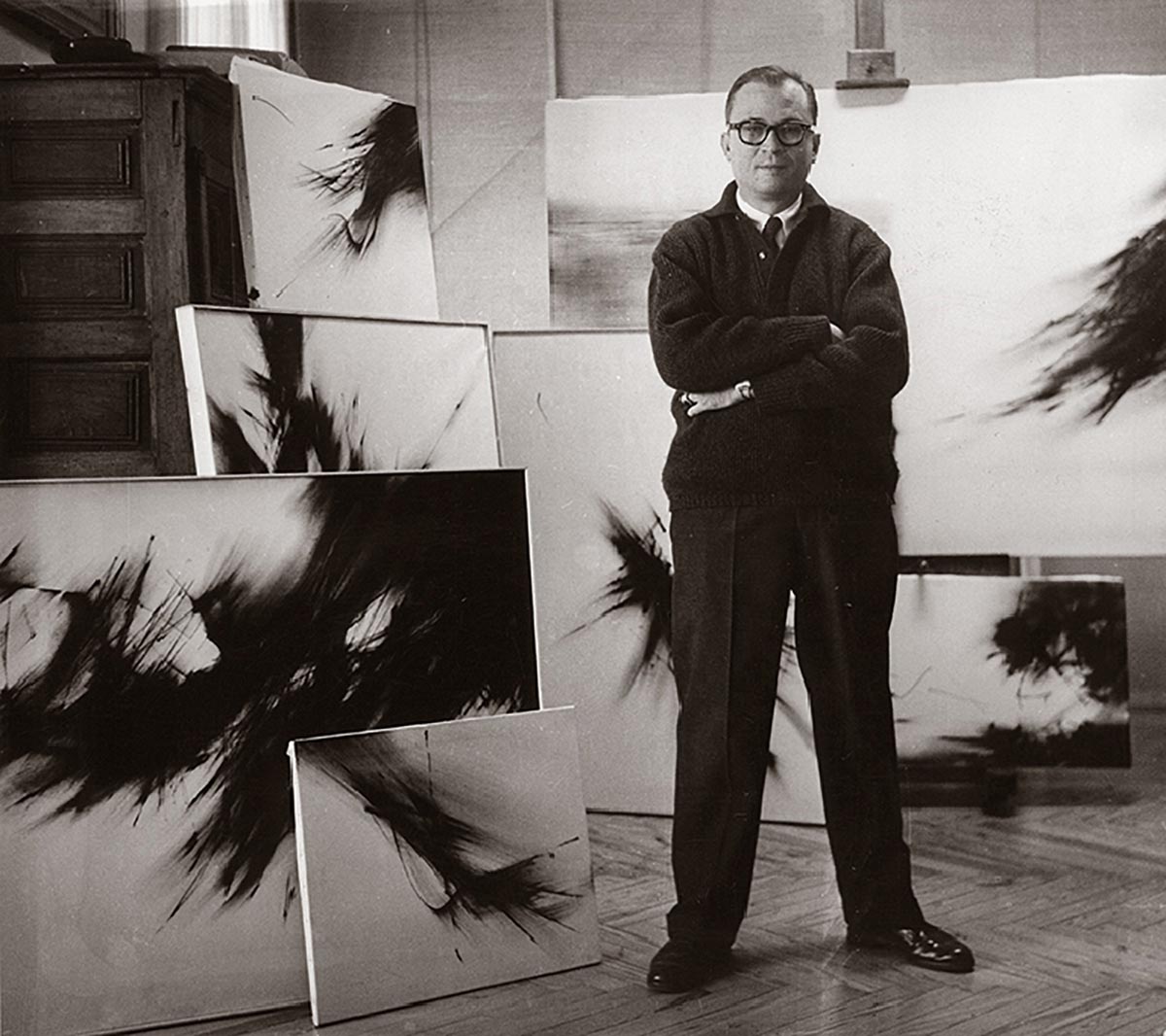

Fernando Zóbel in his Madrid studio, with paintings for the Sala Neblí exhibition

Fernando Zóbel in his Madrid studio, with paintings for the Sala Neblí exhibition

1961In the course of the previous ten years in the Philippines, his interest in archaeology, religious sculpture and contemporary Philippine art had led him to form excellent collections in the three fields and as a final touch to his acts of patronage on the islands, he donates the collections to Manila’s University of Ateneo. The collections will be used to create the Ateneo Art Gallery in June of this year. The paintings in this collection ranged from figurative styles to abstraction and included works by some of the leading Philippine artists of the time, such as Arturo Luz, Vicente Manansala, José Joya and Hernando R. Ocampo 33.

He publishes an article on Philippine porcelain: “The first Philippine porcelain” 34.

1962

Manila’s University of Ateneo grants him the honour of becoming the university’s first doctor honoris causa. He is also awarded the title of honorary director of the museum.

He takes part in a number of collective exhibitions outside Spain, including two of particular note: Modern Spanish Painting at London’s Tate Gallery (the exhibition poster is a reproduction of Zóbel’s Colmenar) and the XXXI Venice Biennale, where he meets Gustavo Torner, amongst other painters 35.

Modern Spanish Painting exhibition at the Tate Gallery with Zóbel's poster reproducing the painting Colmenar

Modern Spanish Painting exhibition at the Tate Gallery with Zóbel's poster reproducing the painting Colmenar

1962In Madrid, he participates in the exhibition, Cinco pintores: Sempere, Rueda, Manrique, Vela y Zóbel at the Galería Neblí.

Group exhibition at the Neblí Gallery with the participation of (from left to right) Gerardo Rueda, Vicente Vela, César Manrique, Fernando Zóbel and Eusebio Sempere.

Group exhibition at the Neblí Gallery with the participation of (from left to right) Gerardo Rueda, Vicente Vela, César Manrique, Fernando Zóbel and Eusebio Sempere.

1962Trip to Chicago. With his friend Mike Dobry, he visits the Chicago Art Institute to see an exhibition of paintings from what is now the Museum of the National Palace of Taipei (formerly the Forbidden City), Taiwan. 36.

About this exhibition, he writes:

“Went with Mike Dobry to see the Gu Gong paintings being shown at the Art Institute. The Song landscapes are much bigger than I thought. The reproductions I knew, being much reduced, gave no idea of the amount of calligraphy involved. I thought that came later. (But content lords it over form. Rembrandt and Velázquez would have felt at home; especially Rembrandt). The Qing ‘scholarly’ paintings, presumably at their best, continue to look sloppy and weak. Am I missing the point? Or are they, as I suspect, primarily framed autographs by mysterious worthies playing parlour games with a brush for each other’s benefit? After all, many of us are doing much the same. Some of the results look terribly inept though, I suppose. The footnotes are all there, terribly amusing to those who can spot them.

Fan Guang “travelers” tickled into gigantic existence, the artist intent on his theme, using the brush stroke as a means, not an end. Mike draws my attention to Xu Daoning’s Fishing on a snowy river. Crisp, decided; calm emptiness. A Japanese emptiness, but without sugar. After a while, the tart and, further, the tasteless, always seem the best. In a sense, how little there is to all this; these flimsy works surrounded by the logorrhoea of the centuries. By contrast, our Louvres and Prados seem dense, heavy, full of furniture and gesticulation. The Chinese world is full of privacy. These works, never intended for a public showing, have an embarrassed look. Assaulted modesty (…)” 37

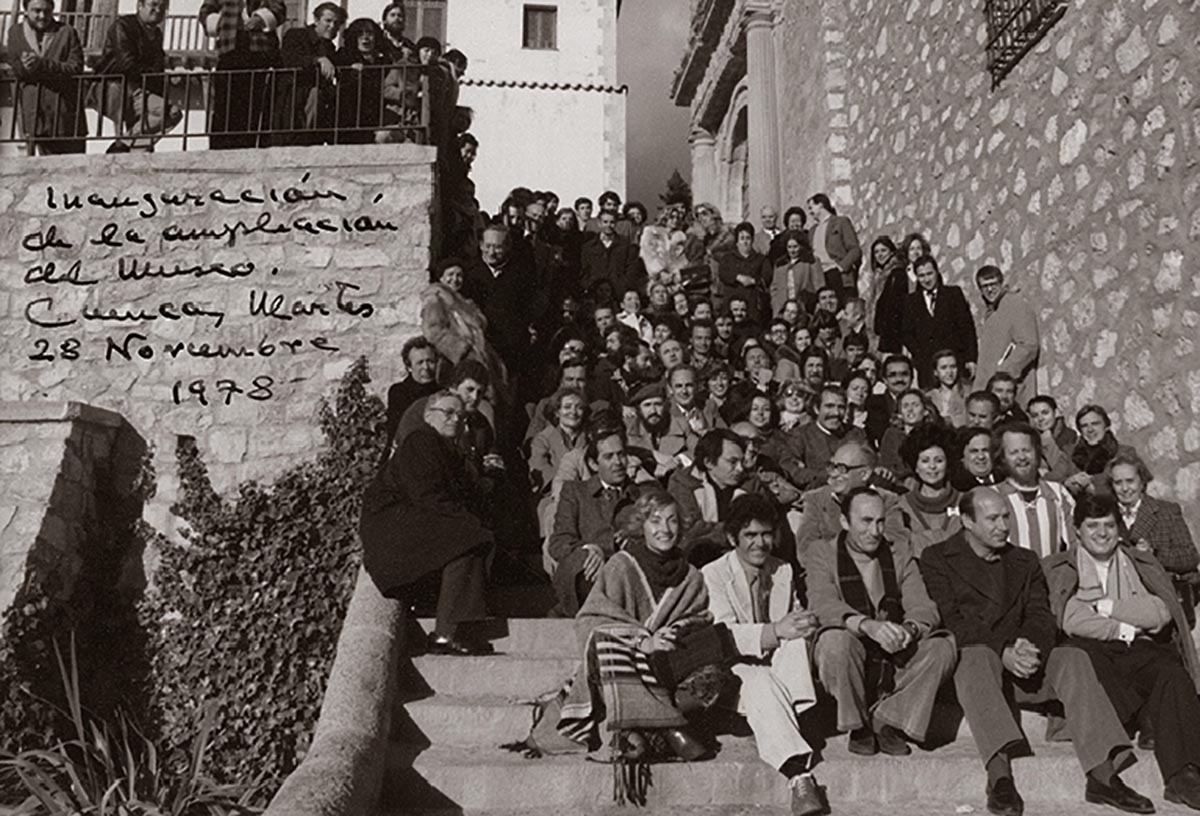

He travels to Venice to attend the inauguration of the XXXI Biennale and also to Rome. Back in Madrid, on July 20, he writes the following:

“It’s almost a week since Gerardo [Rueda], Alfonso [Zóbel] and I came back from Venice. It’s taken me a week to get organized again. I’m finding myself clumsy. My painting, which contains a certain element of virtuosity, forces me to practice it almost every day; the gaps are noticeable. From the trip itself, I have kept about three hundred sketches. The Biennale is a kind of slave market where one smells and is smelled. Too much of pictures. I didn’t manage to see them all. I think I didn’t manage to see even half. I might say the same about the Spanish Pavilion. It looked like a shop window on Calle Hortaleza or Calle Fuencarral. My stuff looked good against the black walls. Its simplicity stood out in the midst of all the panoply. I’ve been offered exhibitions in NY, Chicago, Los Angeles, San Francisco (Feingarten, Bodley), in Rome (La Salita, Don Quixote), in Naples. They seem to be a lot, too many. (…) Manessier, for political reasons and unjustifiably, walked off with first prize. Giacometti, justifiably, walked off with the sculpture prize. His pictures deteriorated greatly in the period from 1957 to 1959. For me, the best things about Venice were the Jean Paul Riopelle and Hundertwasser Pavilions. The latter took me completely by surprise. As we Spaniards had nobody to defend us before the panel, we left empty-handed. (…) President Segni, tired and distinguished, a figurehead in a morning coat, surrounded by clamorously decorative civil servants and military officials, visited each pavilion and came out with an immortal phrase for each artist. By the time he came to my pictures, he was worn out after so much talking and sliced the air with his hands as if he were a plane taking off. He evidently sees things more clearly than many critics. (…) The best thing about the Biennale is Venice. That enormous toy. (…) Anything that can be said about Venice has already been said. It is being worn away by so many eyes looking at it. (…) We go back to Rome, looking at all the fountains that appear in our path. (…) Wonderful retrospective exhibition of Mark Rothko. New colors, vibrant and sombre. The best pictures I see from start to finish of the trip are, with the exception of a Bonnard in Venice, a female nude in front of a mirror of twisting, sizzling colors. In Italy, all is color. I feel this great urge to buy a box of watercolors and mess around a bit. To paint with glaze. Also: the small Etruscan bronzes at Villa Giulia are marvellous.

I draw wherever I go; in Venice, Tintoretto, in Rome, fountains and water. I buy myself a bronze Roman lantern, a sestertium of Lucio Vero, a cut gemstone from the eighteenth century, an engraving of two girl’s faces by Renzo Vespignani. (…)”

In Madrid, he moves to another house and study at number 12, Calle Fortuny.

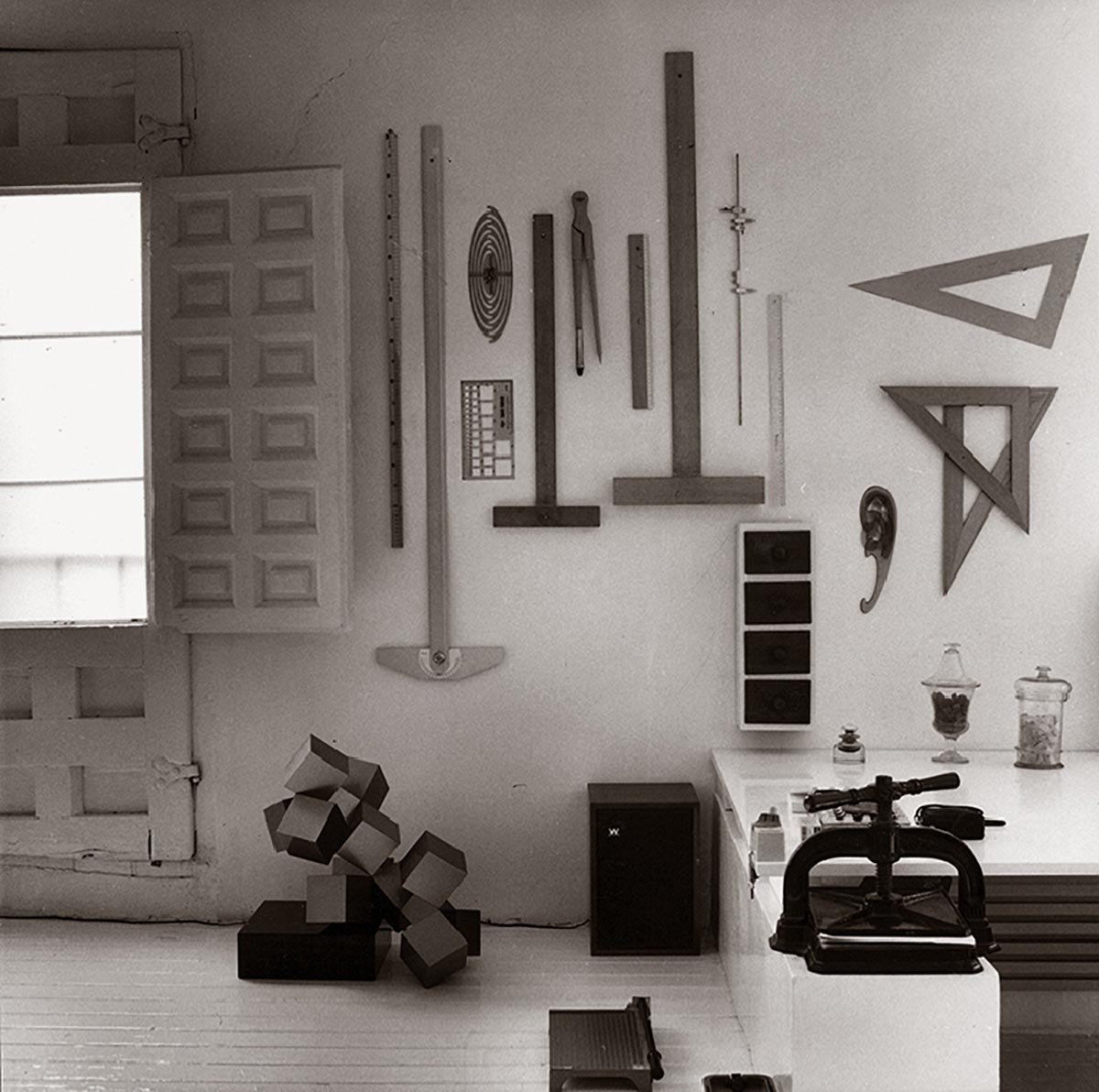

He starts engraving with Dimitri Papagueorghiu and becomes actively engaged in etching with Antonio Lorenzo. About his engraving activities, he writes frequent letters to his North American engraver friend, Bernard Childs. He travels to Paris with Antonio Lorenzo and Gerardo Rueda. October. Visits to the Louvre, some galleries and his friend Bernard Childs, who gives them an engraving session. Childs is the friend to influence him most, the one to show him the secrets and problems of inks, plates, paper, etc.. 38

About his visit to Childs’ studio, Zóbel writes:

“Antonio and I watching Childs engrave. He’s impressed by Antonio’s etchings – ‘only two weeks’. An interesting detail: The time Bernard spends from inking the plate to finally passing it through the screw press is two and a half hours. He wastes no movements. He inks with a spatula and cleans with a piece of newspaper. In the inking process, it’s as if he were painting each plate. There is nothing more pleasurable than watching somebody do something he knows how to do really well. When inking a plate, Bernard uses his head more than most of the painters that I know use theirs when they’re painting a picture. (He doesn’t like etching, he finds it indirect). When we leave the studio, we’re in a daze, our heads bursting, and we go to Charbonnel to buy materials”.

This anecdote is completed by the one told by painter Antonio Lorenzo in the prologue to the catalogue of his graphic work. He tells of how he became interested in engraving as a result of the trip to Paris with Zóbel. “It was not until 1960, during a trip to Paris with Fernando Zóbel and Gerardo Rueda, that I became interested in engraving. It happened in the Paris study of North American artist Bernard Childs, an old acquaintance of Zóbel’s. We became friends. I showed an interest and he let me soak the paper and turn the shafts on the screw press… Bernard Childs initiated me, and Zóbel, who was also there sometimes – he would spend the day hunting for books and engravings – and was aware of my weaknesses, acted as tempter by rushing me off to Charbonnel to buy inks, scrapers, punches, polishers and lots of other things, rounding off our purchases with a small screw press. We dismantled the shafts and put it in the boot of the car.” 39

On his way to Manila, where he usually goes for Christmas, he stops off at New York. He makes this journey in the year when pop art is at its height in the United States. While he is there, Zóbel visits the historic exhibition, New Realisms, at the Sidney Janis Gallery. He writes of it as follows:

“Super exhibition at the Janis. Super catalogue. Everything’s super except the objects. I found them forced and boring. At Wittenborn, I see a book: Do-it-yourself collages. Critics think that modern art has revolutionized publicity art. It’s the other way round.” 40

One year later, on November 17, 1963, he writes on the subject again

“Pop art feeds off the advertisement, the photograph, vulgarity. To my mind, this double digestion is excessive; the first is quite enough. The rasping sensation produced by the pile of cans of soup is something I feel and have felt perfectly without needing Roy Lichtenstein or Andy Warhol to show me. (But it’s an art for the public). They’ve got the wrong idea with this fashion game. You have to look for the other, the thing that doesn’t change, the thing that serves. What they’re doing here is a kind of tickle.”

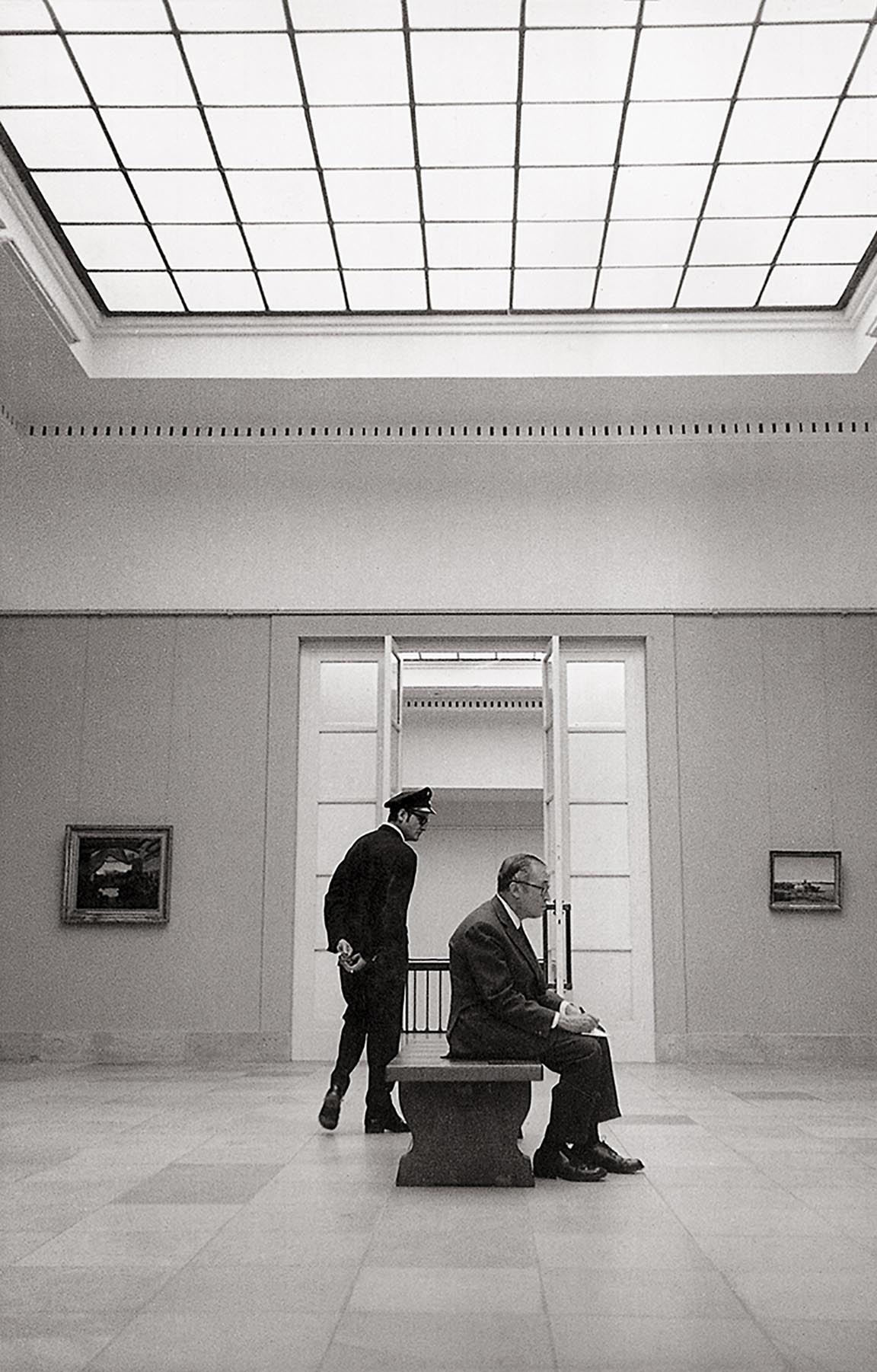

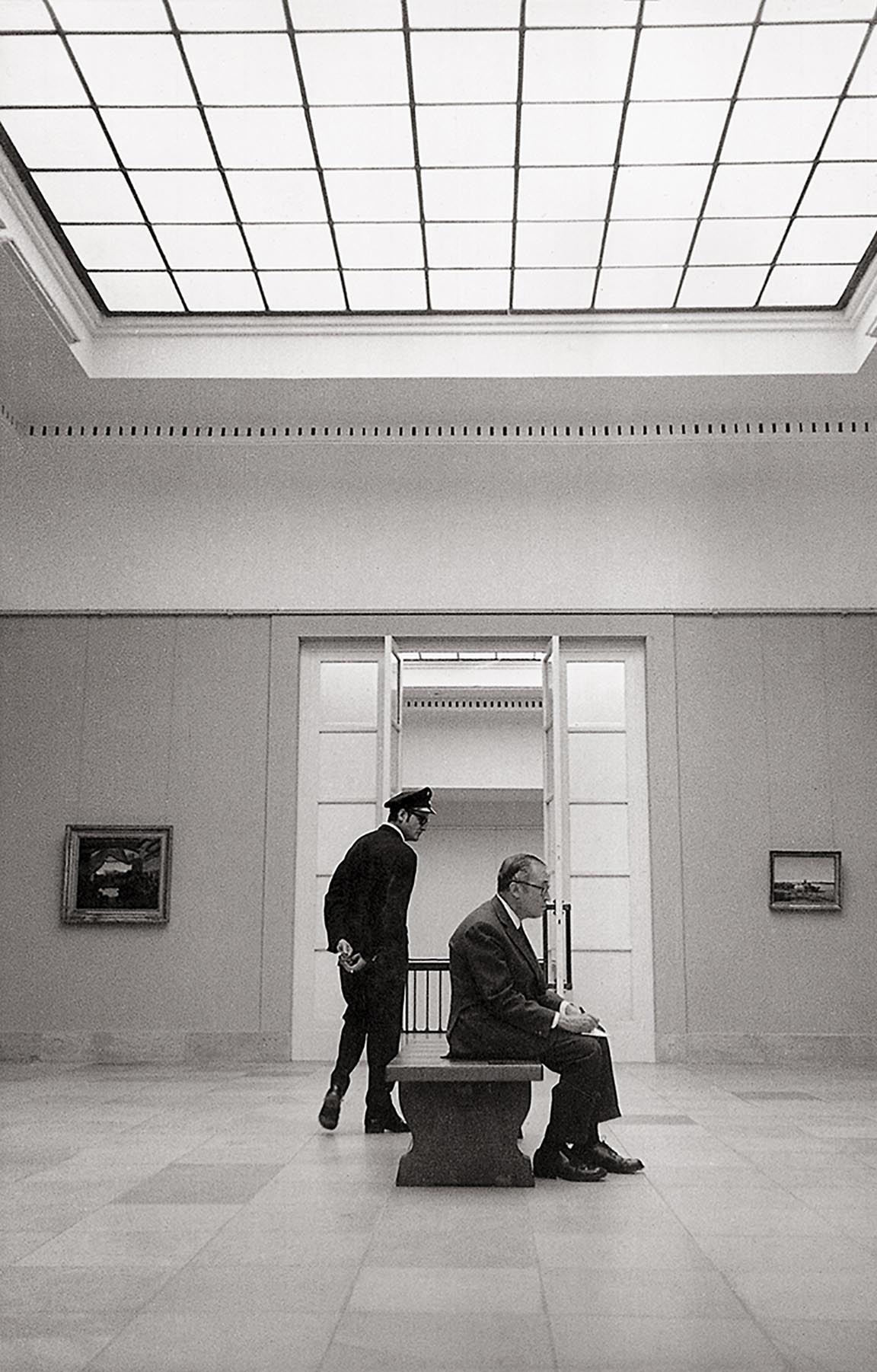

His visits to the Prado are constant. He unfailingly carries his notebook with him so as to study and analyze the paintings of the past with his pen. As his visits are long, he applies for a Prado copier’s card so that he may sit and draw in comfort. 41

He develops an interest in bullfighting (there are countless bullring drawings and observations in his notebooks). He collects Spanish blue and white ceramics from the fourteenth to eighteenth centuries and silverware in the Spanish baroque style.

Fernando Nuño exhibits his photographs of artists in the Sala del Prado at Madrid’s Ateneo, including some taken of Fernando Zóbel while painting.

Zóbel started to buy works by Spanish painters of his own generation in 1955. Between then and now, his still small collection includes works by Antonio Saura, Gerardo Rueda, Luis Feito, Guillermo Delgado, Antonio Lorenzo, Manuel Millares and Eusebio Sempere. At the end of the year, before setting off for the Philippines, Zóbel mentions the “Toledo Project” (the future Museum of Abstract Art) for the first time. This is his first idea about what to do with his collection of paintings by Spanish abstract artists.

“I leave reluctantly. I say goodbye to Antonio [Lorenzo] and Gerardo [Rueda]. We talk about the Toledo Project.” (Madrid, November, 27, 1962).

This year witnesses the completion of Serie Negra with Ornitóptero (1962).

1963

The years elapsing between 1963 and 1975 constitute the longest stage in Zóbel’s painting. This year, he returns to color and slowly, the siennas, dark browns, ochres and greys start to appear, as in works like Atienza, Armadura III and Pancorbo. The theme of memory, hinted at in previous series, begins to take shape in this new stage, in which Zóbel, by means of forms, objects and imagination, seeks “to remember in pictorial terms”, as he himself put it. In the prelude to this colorist stage, Zóbel develops the idea of painting based on the memory of the experience lived, a concept whose literary equivalent is to be found in Marcel Proust’s great work, À la recherche du temps perdu. About Proust’s influence on his work, Zóbel is very clear when he speaks of Homenaje a Patricio Montojo (1963), now in the Museo de Arte Abstracto Español:

“I have always been struck by the part in Côté de chez Swann where Proust describes a walk round Cambray – a walk in a country and a time which aren’t mine initially but become mine in the end; to put it another way, as I read, I recognise, with a strange, inexplicable nostalgia, the relish of my own childhood. On another occasion, over two years ago, I think, I decided to try a kind of painting based on memory; by this, I mean a climate painting, leaving the viewer to complete it with his memories. The realist focuses on that loaf of bread, that flower. I’d like to create a climate in which the bread, the flower, were born of the viewer’s imagination. There is something of this in Homenaje a Patricio Montojo: I discussed this at length with Toni Magaz last night. It’s not that it’s about a naval battle. Obviously, the picture is an abstract composition. But, from my point of view, as I use elements exterior to the picture, and from Toni’s, who contributes personal elements quite similar to my own, it is clearly a naval battle. An educated North American would probably see it as a scene from Melville. This morning, Rubio Camín turned out a landscape of plateaus (figuration always proves clear, bordering on the most extreme realism. However, it varies from person to person, the plateau as clear as the battle). The painting establishes the climate, ‘in the order of’, as Torner would say. The viewer completes it with his subjective experience, which, for me, translates into a battle (complete to the last detail with lights, the floating tree, gunpowder on the water) and for Camín, it translates into a plateau (rocks, parched plants, mists, a shepherd’s cottage and so on). Ortega’s definition of the cannon: ‘You take a hole and surround it with iron…’ etc. (The picture as a hole filled by the viewer. I provide the iron that gives shape to the hole). Retrospectively, previous works fill out with meaning: El Faro, La primera amapola and so on. A complete scenario of painting opens up; an approach as yet untried. Subjective painting (until now, rendered subjective by the painter); now aimed at the viewer. Painting as a mirror. I’m expressing myself badly because I still don’t have a clear idea about the limits and possibilities. All this will fall into place with time.” 42

Exhibition of drawings at the Galería Fortuny, Madrid. A book of his drawings is published: Zóbel. Dibujos, drawings, dessins, with a text by Antonio Lorenzo43.

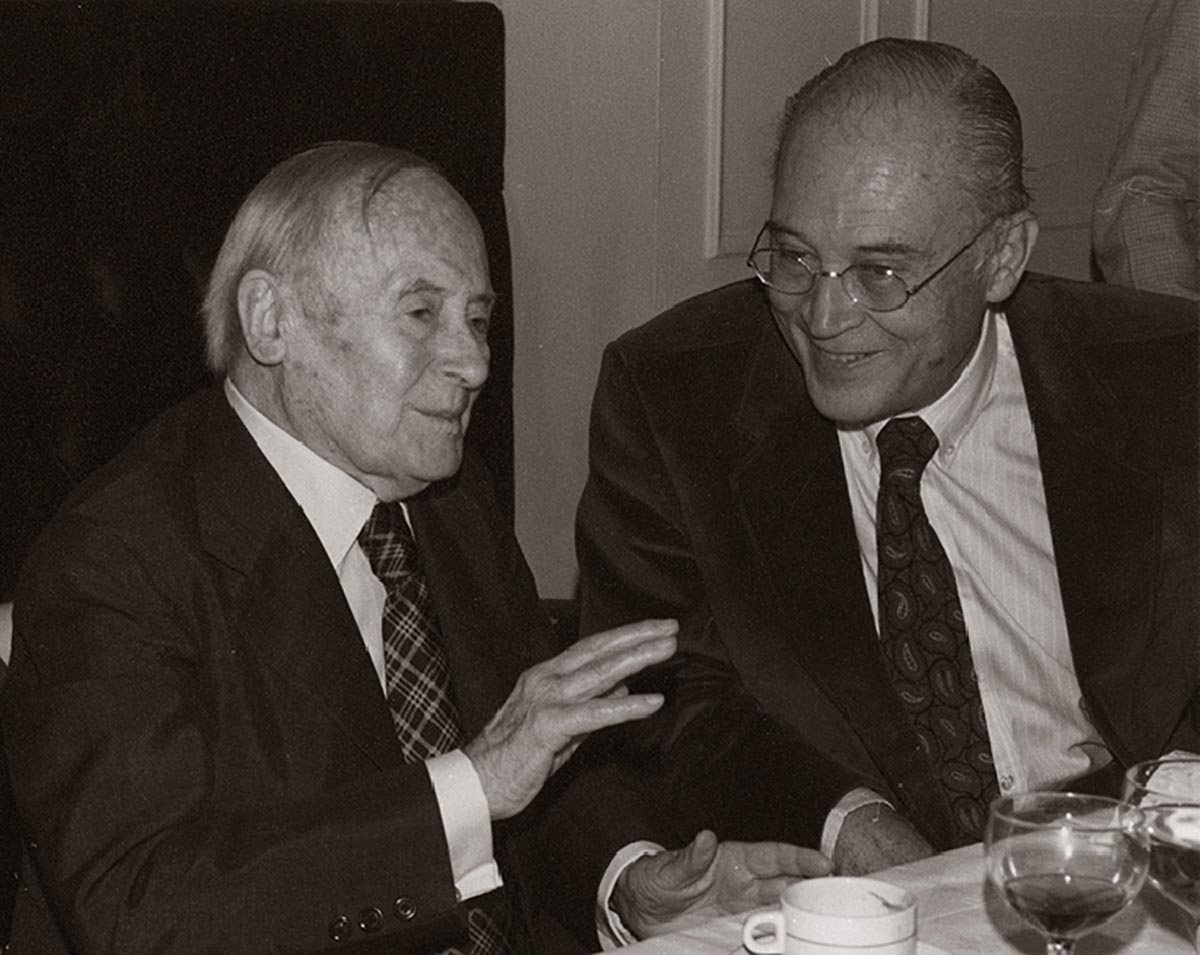

With Manolo Millares at the opening of the exhibition of Zóbel's drawings at the Fortuny Gallery in Madrid

With Manolo Millares at the opening of the exhibition of Zóbel's drawings at the Fortuny Gallery in Madrid

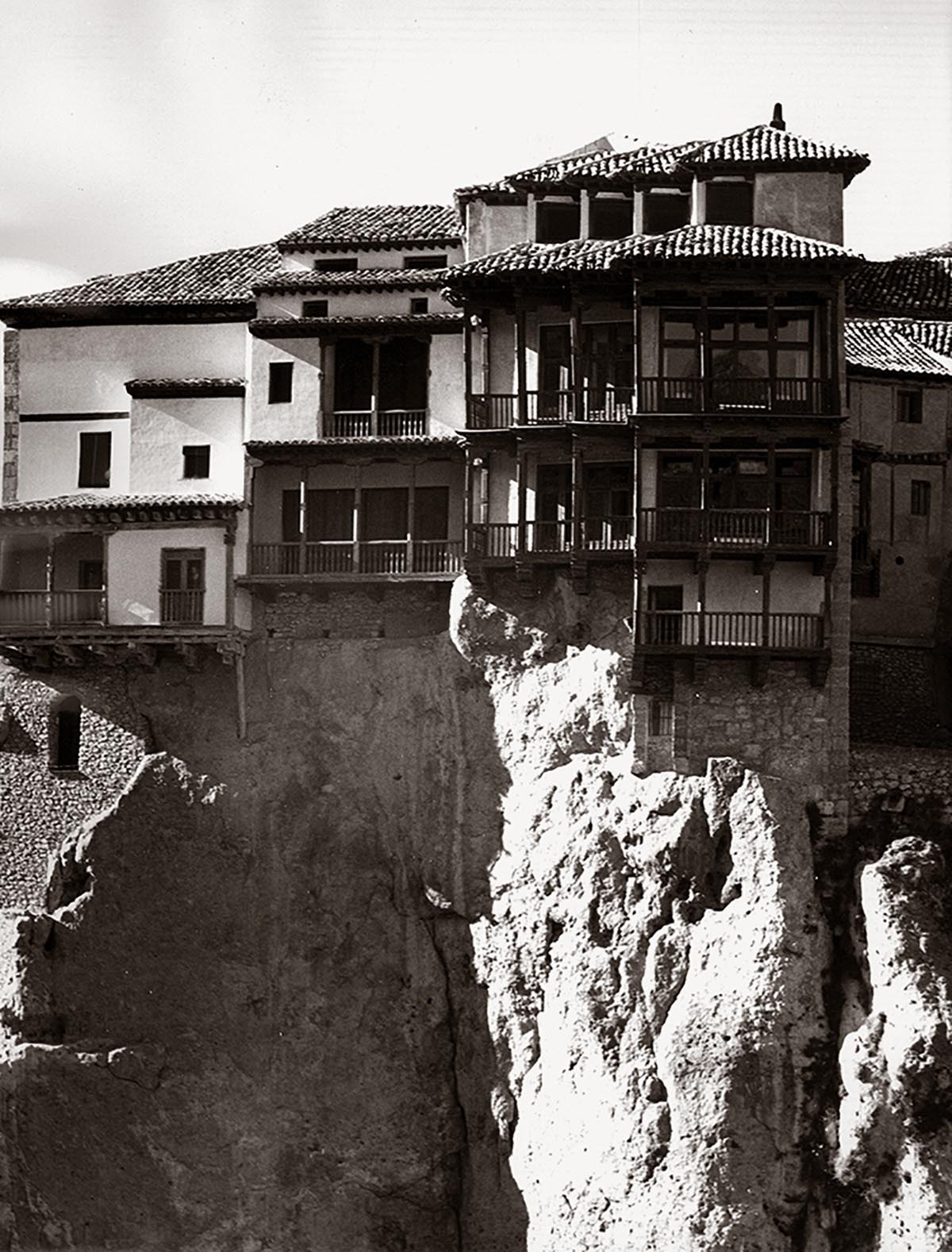

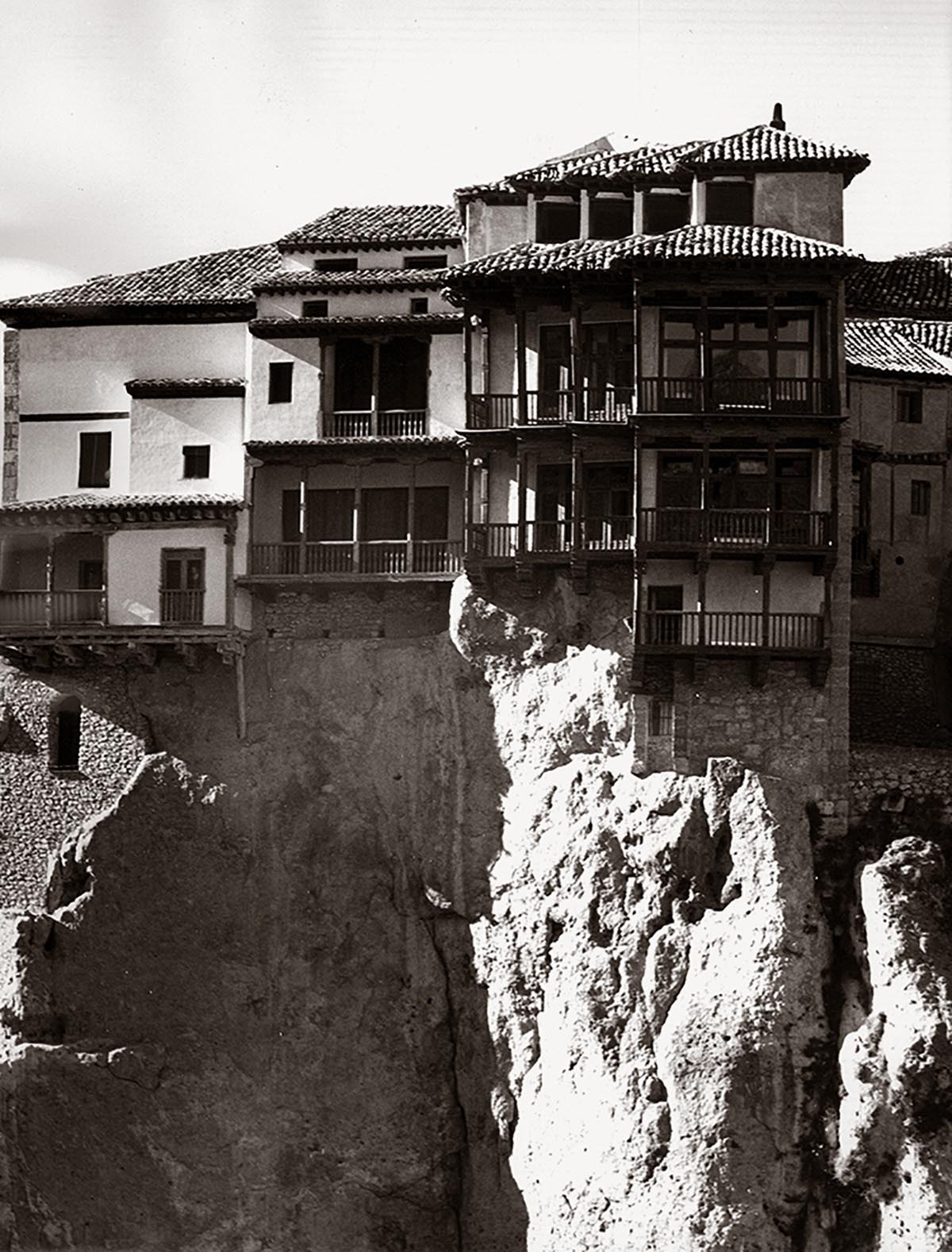

1963As the year elapses, the idea to install a painting collection somewhere outside the four walls of his Madrid home begins to take shape. With this view in mind, in April, he goes to Toledo with Gerardo Rueda, but fails to find anything satisfactory. A few days later, Gustavo Torner invites him to spend the day in Cuenca to show him his house and take him round the city, along with José María Agulló, Rafael and Carmen Leoz and Juana Mordó. In June, the museum project starts to develop when, through Gustavo Torner, the Mayor of Cuenca offers him the possibility of installing his collection in the building of the “Hanging Houses” (at the time, the houses are being renovated and no decision has been taken as to their future use). On seeing the houses, Zóbel does not hesitate. On June 16, after visiting the “Hanging Houses”, he writes:

“Two days in Cuenca with Torner and Lorenzo. The mayor, Rodrigo Lozano de la Fuente, goes out of his way to help us and find solutions. We take a look. A magnificent museum could be installed in the “Hanging Houses”. 20 to 30 years paying a nominal rent and the pictures are my property. The buildings are handed over to me ready for use but, from then on, expenses are on my own account. (…) I see it as a good proposition, a nice thing to do and it saves me from spending nearly a million pesetas on a house. I can use that money to buy pictures. The best idea would be to encourage painters to come and spend the summer here. You have to make the most of your opportunities as they arise. Otherwise, regret sets in.”

The fact that there is now a space to house the collection affects decisions as to its content and, from now on, Zóbel will consider it necessary to have a more complete representation of Spanish artists belonging to the abstract generation. He selects the works and always asks the artist to give his opinion. As he accepts neither gifts nor donations, he is in a position to act quite freely. He usually buys the works directly from the artists, although he sometimes goes to the galleries, or exchanges his work for that of the artist, or the artist produces a work specifically for the museum. He then forms a team with Torner and Rueda, who will be responsible for adapting the museum’s spaces and installing the paintings. In July, Zóbel takes up residence in Cuenca. In September, he starts work on the museum. Full of enthusiasm about the museum project, Zóbel writes to his American friend, Paul Haldeman (October 4 1963):

“My big project is a Museum of Spanish Abstract Art in the city of Cuenca – two and a half hours from Madrid. In the renowned “Hanging Houses”, which the kind-hearted, forwardlooking local corporation has let me rent for thirty years at something like 1.50 dollars per annum. How nice fo everybody! I have a feeling it is going to turn into one of the loveliest small museums in the world. As I will be owner, director, curator, acquisitions committee, patron, board of trustees and dictator, I rather think I shall have a lovely time. My life’s ambition: a final club with only one member – me. (There will be room for only about 40 paintings but they shall hang with all the glamour that my fervid jeweller’s imagination can devise).”

In October, he buys Sarcófago para Felipe II (1963) by Manuel Millares, one of the museum’s most important works. After visiting the artist at his studio, he writes:

“The other day, Manolo Millares called me. He’d heard about the museum and he told me that he had a couple of pictures he wanted me to see before Pierre Matisse arrived, because he likes them and, above all, he would like one or two of them to stay in Spain. I went with Gerardo after lunch. (…) He tells me that, after painting, his greatest interest is archaeology. We see the paintings. An excellent triptych built round bottoms and corsets, an allusion to the Profumo Case. To me, it seems a bit of out of character for Millares and, what’s more, it is far too clichéd. I prefer the other one, a huge diptych depicting a sarcophagus, the body of Felipe II, or whatever. For all the poor quality and coarseness of the matter, it is astonishingly elegant. The difference between pop art and Millares is that Millares takes an aesthetic approach, he composes. The shock is not the issue; it is more like a tip or something of the sort. He himself says: ‘I haven’t the slightest interest in neo-Dada.”

One year later, he buys another work from him, an arpillera (a technique whereby scraps of fabric are appliqued onto a hessian backing) titled Cuadro, which is reproduced in the first catalogue Zóbel publishes for the Museo de Arte Abstracto Español in 1966. Also in 1963, he buys two works from Manuel Rivera, Espejo de duende and a landscape.

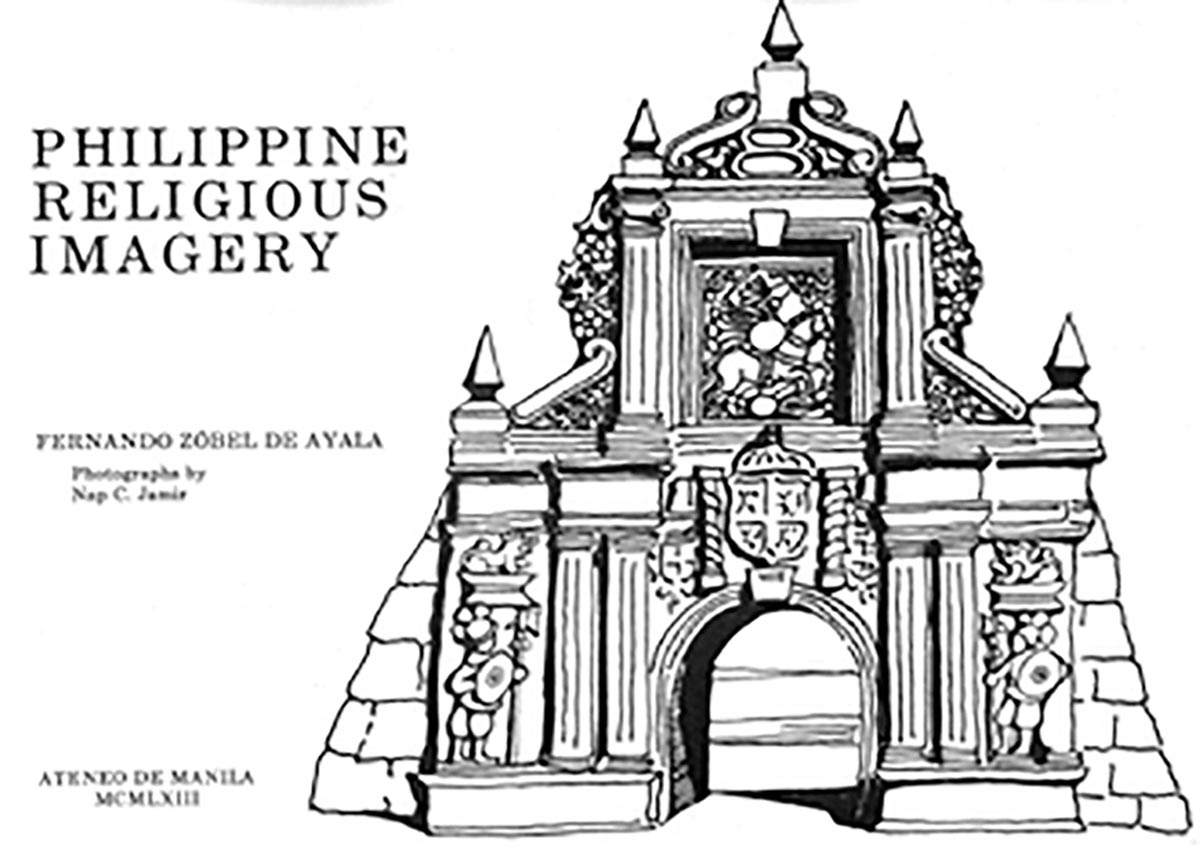

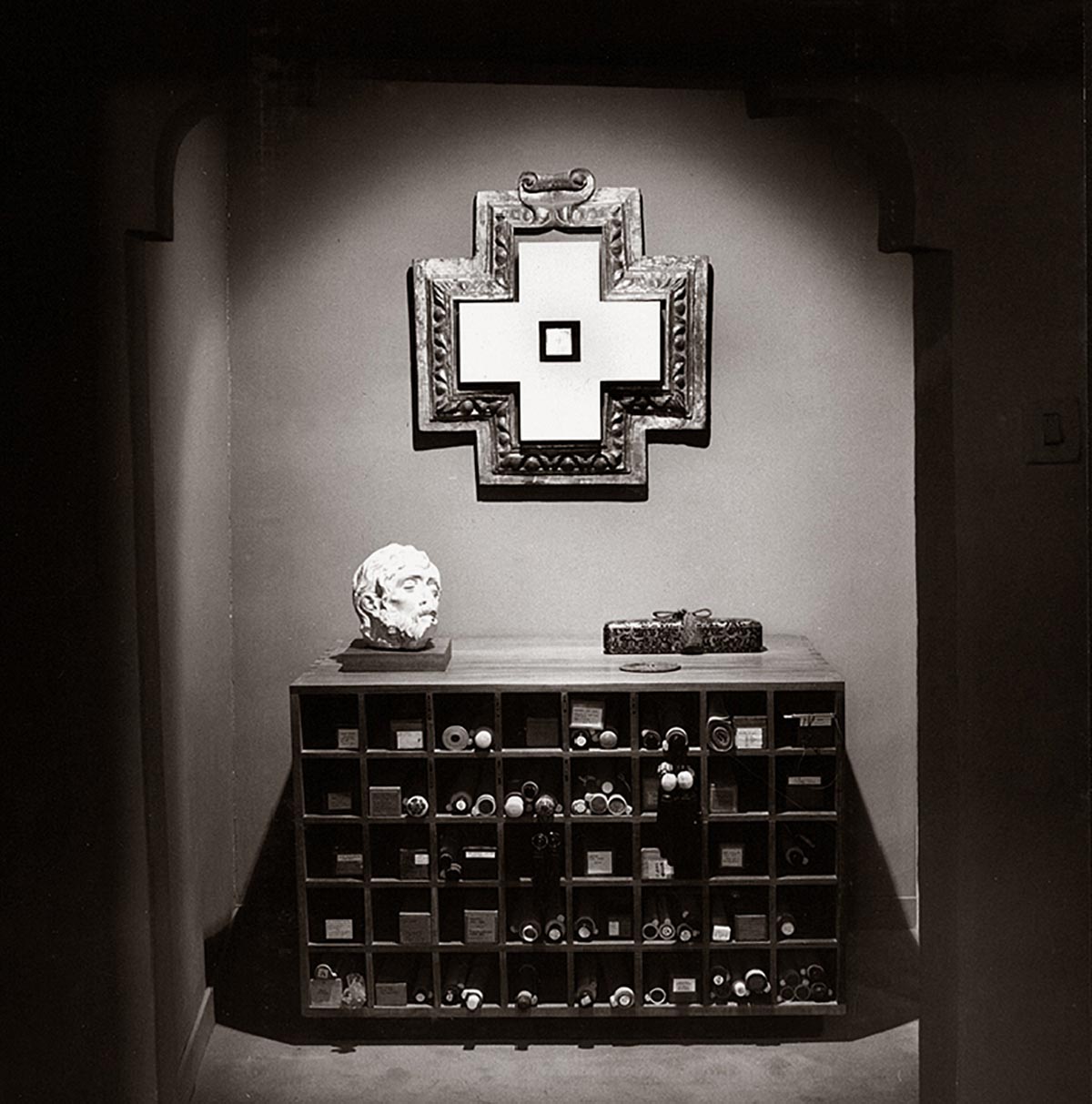

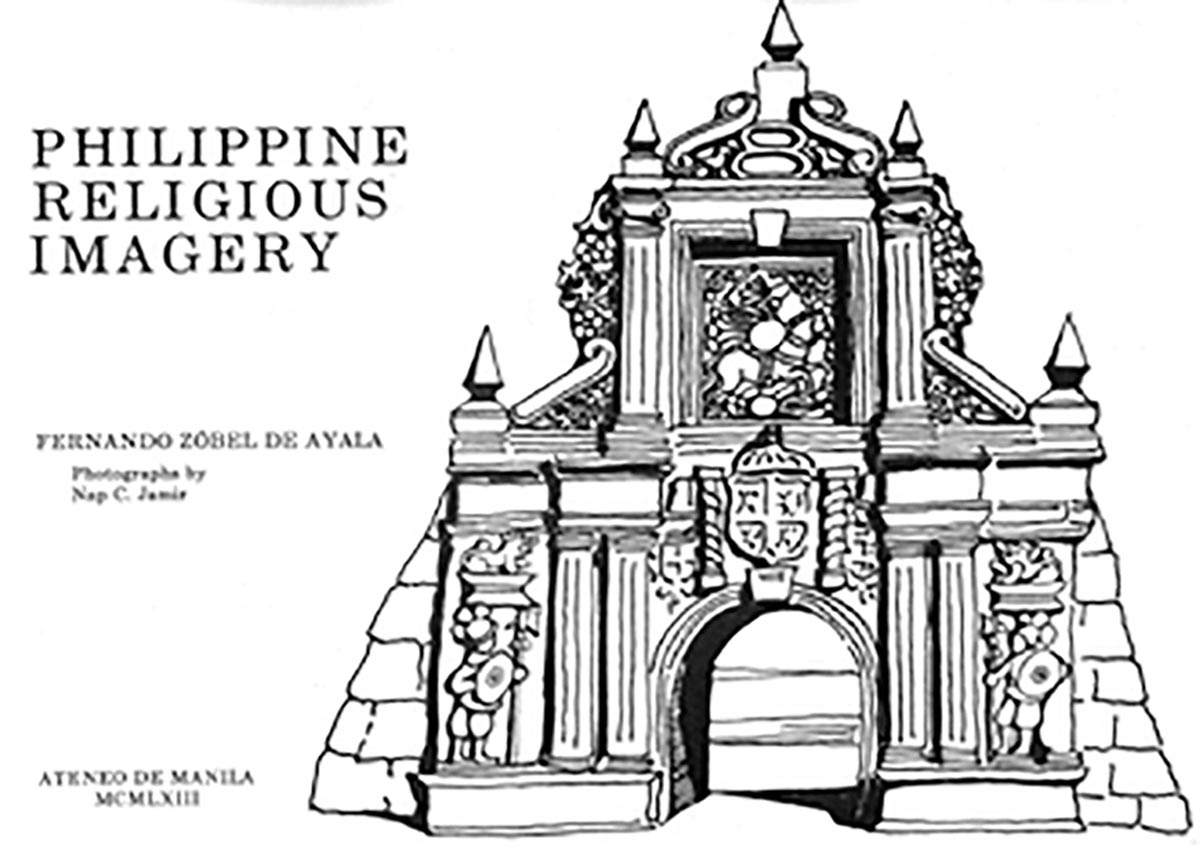

This year, he concludes his research into Philippine art and publishes in Manila an impeccable study titled Philippine Religious Imagery, about Philippine images painted, sculpted or modelled during the period of Spanish domination from 1565 to 1898. In this study, Zóbel reaches the conclusion that, beyond any doubt, the best area in which to study the existence of a Filipino style with its very own characteristics is colonial statuary.

Zóbel publishes in Manila an important study on Philippine religious imagery under the title Philippine Religious Imagery.

Zóbel publishes in Manila an important study on Philippine religious imagery under the title Philippine Religious Imagery.

1963Lectures: one titled El renacer de la pintura española, on the rebirth of Spanish painting, at the Colegio de Leyes del Ateneo de Manila, and another about the Eastern painter, El mundo del pintor oriental, given at a course organized by the Cátedra San Pablo, Madrid.

1964

He rejects the offer of the Professorship of History of Art at Mills College, Berkeley (California)

Individual exhibition at the Luz Gallery, Manila. He also works on a series of etchings at the studio of painter Manuel Rodríguez, in Manila.

In Madrid, individual exhibition at the Galería Juana Mordó, inaugurated this year by the gallery owner of the same name. It is his first exhibition in Spain after his return to color.

Trip to New York to participate in the Spanish Pavilion at the New York World’s Fair and to finalise the details for his exhibition at the Bertha Schaefer Gallery, to take place the following year.

This is a year of intense activity at the museum, with acquisitions, trips, visits to studios and so on. In a remarkably short time, Zóbel succeeds in drawing a good number of artists to Cuenca, all of whom are enthusiastic about the idea of the museum. By Easter of this year, in addition to Antonio Saura and Gustavo Torner who actually live there, Gerardo Rueda, Manuel Millares, Manuel Hernández Mompó and Amadeo Gabino have studios in the city. And Zóbel writes:

“Mompó arrived yesterday to stay at the house. Millares and Serrano went the day before. Escassi is staying with Ángeles Gasset. I saw Greco and Adriansens on the street. The place is full of painters. It is also just plain full”

This year, he buys a number of works from José Guerrero, Gustavo Torner and also from Manuel Hernández Mompó, who executes Semana Santa en Cuenca expressly for the museum. The inclusion of Chillida in the collection is another of the objectives for this year. Through Antonio Saura, the two artists meet in Cuenca in May and Zóbel asks him to make a piece for the museum. 44. At the end of this year, Chillida tells Zóbel that he has completed the sculpture for Cuenca: Abesti Gogora IV (1959-1964). 45.

With regard to this sculpture and his conversations with Chillida in various encounters, Zóbel writes about the quality of the Basque artist’s thought and work with extraordinary lucidness:

““Chillida, as friendly as ever, tells me that the sculpture is ready. It’s big. A point of departure for an even bigger one. Maeght doesn’t charge commission so we get it for half the normal price: about 350 k (this may be cheap for a Chillida, and indeed it is, but it nearly used up all my resources). From the photograph, you can tell that it’s made of wood, compacted with that strange way of not missing a single detail, so characteristic of Chillida. He’s been turning it over in his mind for three years. (…) From a very early age, Eduardo has wanted to become an artist. The biggest problem he had to face was giving up the architecture degree course he’d started. He didn’t want to upset his family but in the end, he found himself forced to abandon the course halfway through. He was talking about the days when he used to play football and about his reputation for ending all the matches in a fight. He has no cuttings from this period of glory and his children (eight of them) can hardly believe him when he says that he played for Real Madrid. (…) He works slowly. His ideas spring up as he works. He’d been working on Abesti Gogora IV for Cuenca since 1961 and finished it just a couple of months ago. Once the work is finished, he doesn’t mind parting with it; he knows it by heart (with Manolo Mompó, on the other hand, it’s an entirely different matter. Taking a drawing away from Manolo is like pulling out one of his teeth (…).” “Eduardo Chillida is here for the Canada Cup. He loves golf. He game to dinner with Pili plus Lorenzos. He felt like talking and talked steadily and rather beautifully until two. Mainly, it was Antonio and myself who kept prodding him.

In Paris, the two horrible years between figuration and abstraction where he worked every day and could get nothing done. At one point, he decided to return to figuration to recover his footing and found, to his horror, that he no longer knew how. Panic. He walked the Quais for hours – at one point, he remembered stopping in front of a shop window full of clothing – dummies, and telling himself, ‘At least the man who made those knew what he was doing.’ He decided that perhaps Paris was pushing him out of shape, and he returned to Hernani, recently married, short of funds, the future a complete fog. The lowest point of his life. He suspected that he had burnt himself out as a sculptor

Those drawings of hands. He didn’t do them while he was sick; what he did when he was sick was a whole series of squiggly Indian ink abstractions drawn with a Chinese brush. (…) My Abesti Gogora, the first of the series; his first sculpture in wood. It took years to finish, with many pauses and false completions. It used to be much larger than it is now. ‘The heart is still the same, anything superfluous has to be removed. The sculptor does not see in the same way as a painter does. He looks at things deeply. If he were doing your portrait, he would cease to see a profile. He would focus on the centre of your skull and from here, from within, the forms would issue forth.’ Dismisses Calder, Henry Moore (…). Likes Giacometti, Lippold. A passion for Medardo Rosso. Told me to check out a virtually unknown, older Spanish painter in Paris, named Fernández. Virtually unknown. Very honest. I asked him to send me photographs or something. We got to talking about people who write about art. Started translating from Lin Yutang’s collections of Chinese excerpts. He was fascinated. ‘I must have something Chinese somewhere inside my body.’ His own favorite is Gaston Bachelard. Those bearded youngsters look down their noses at him; most of the time, they don’t have the slightest idea what he is talking about. Bachelard wrote the introduction to Chillida’s first catalogue. Chillida moved heaven and earth to meet him; once they’d met, there was a meeting of minds almost instantly. Chillida merely wanted permission to quote from Bachelard; ‘mais nous sommes frères!’, said poet to that and wrote the presentation. (…) Chillida never makes models, he draws to establish the mood, then lays the drawings aside and attacks his final materials directly. He tried working from a model once and the results were disastrous. (…)”

He publishes an article about Gerardo Rueda in Manila 46, 6 and also in this year, writes the prologue to the catalogue for the exhibition of the Johnson collection, Arte actual USA. This exhibition is organized by the Directorate General of the Fine Arts and is held in Madrid, at the Casón del Buen Retiro.

1965

A short trip to Manila, where he prints a portfolio of 24 small etchings, Libro de horas, at Manuel Rodríguez’s workshop, and gives the lecture, Philippine Folk Art.

He travels to New York on the occasion of his individual exhibition at the Bertha Schaeffer Gallery.

Individual exhibition at the Galería Sur, Santander.

Once he has decided to set up the Museum of Abstract Art in Cuenca, his trips to this city are constant; for years, it will be on the road and in the city that he will find most of his themes for landscapes, as in Tarancón (1964), Balcones (1964), Carretera de Valencia (1966) and many others which he will paint in the course of time. Little by little, the city and its surrounding area take possession of the painter and Cuenca fills his notebooks, his pictures and also his writing. In April, back in Cuenca after visiting Manila and New York for the purpose of his exhibition, he writes:

“As we drive, tensions uncoil. New York seems infinitely remote. I begin to feel like myself again after we pass Tarancón. Flat, cold light with clouds. Felled trees on both sides of the highway for a widening that may take a decade to come. The almond blossoms are gone and the poppies have not yet come; spring on the verge of its second wind. Slowly, my appetite for the shape and color of the meseta reawakens and I begin to feel like a painter again. I haven’t really touched a brush in almost three months.”

Trip to Barcelona in October, with Gerardo Rueda and Gustavo Torner, to visit Tàpies at his studio and buy a major work from him for the museum. Zóbel had already reserved Grand Equerre at the Stadler Gallery in Paris, but he wants to know Tàpies’ opinion on the matter. In the end, in accordance with Tàpies’ opinion, this is the work he chooses.

1966

Death of his mother, Fermina Montojo y Torróntegui.

Individual exhibitions at the Galería Juana Mordó in Madrid and Galería La Pasarela in Seville, where he gives alecture about the Spanish abstract painting of the Cuenca Museum, Pintura abstracta española en el Museo de Cuenca.

Zóbel paints little while the works at the museum are going on. He hangs but two of his pictures: Ornitóptero (1962) and Pequeña Primavera para Claudio Monteverdi (1966).

With Hans Hartung, Antonio Lorenzo, Juana Mordó, Luis Figueroa Ferretti, Eusebio Sempere and Amparo Martí.

With Hans Hartung, Antonio Lorenzo, Juana Mordó, Luis Figueroa Ferretti, Eusebio Sempere and Amparo Martí.

Hartung's exhibition at the Sala Neblí. Madrid.

1966Inauguration of the Museo de Arte Abstracto Español of Cuenca on June 30. The following day, he writes the following about the event:

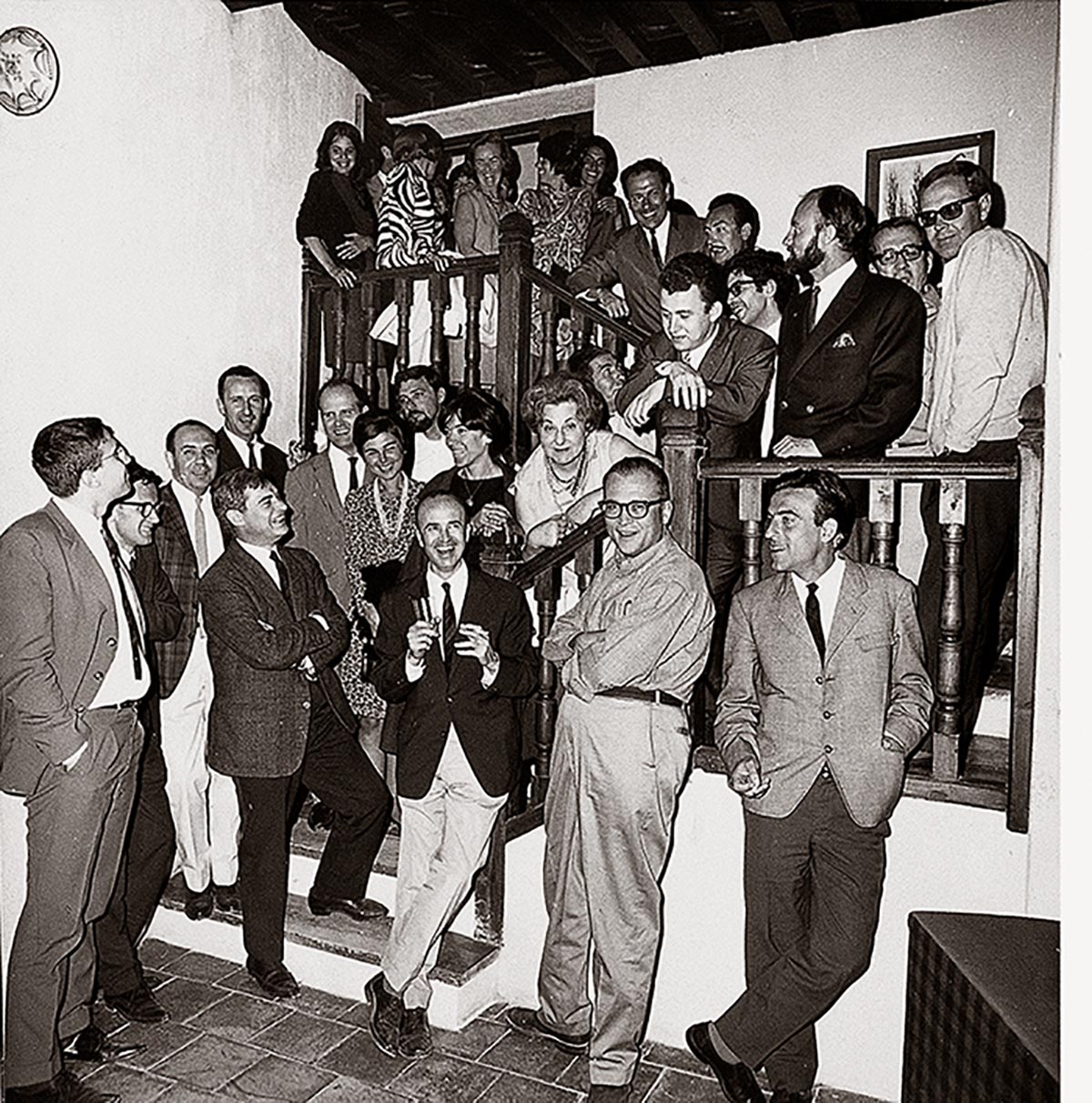

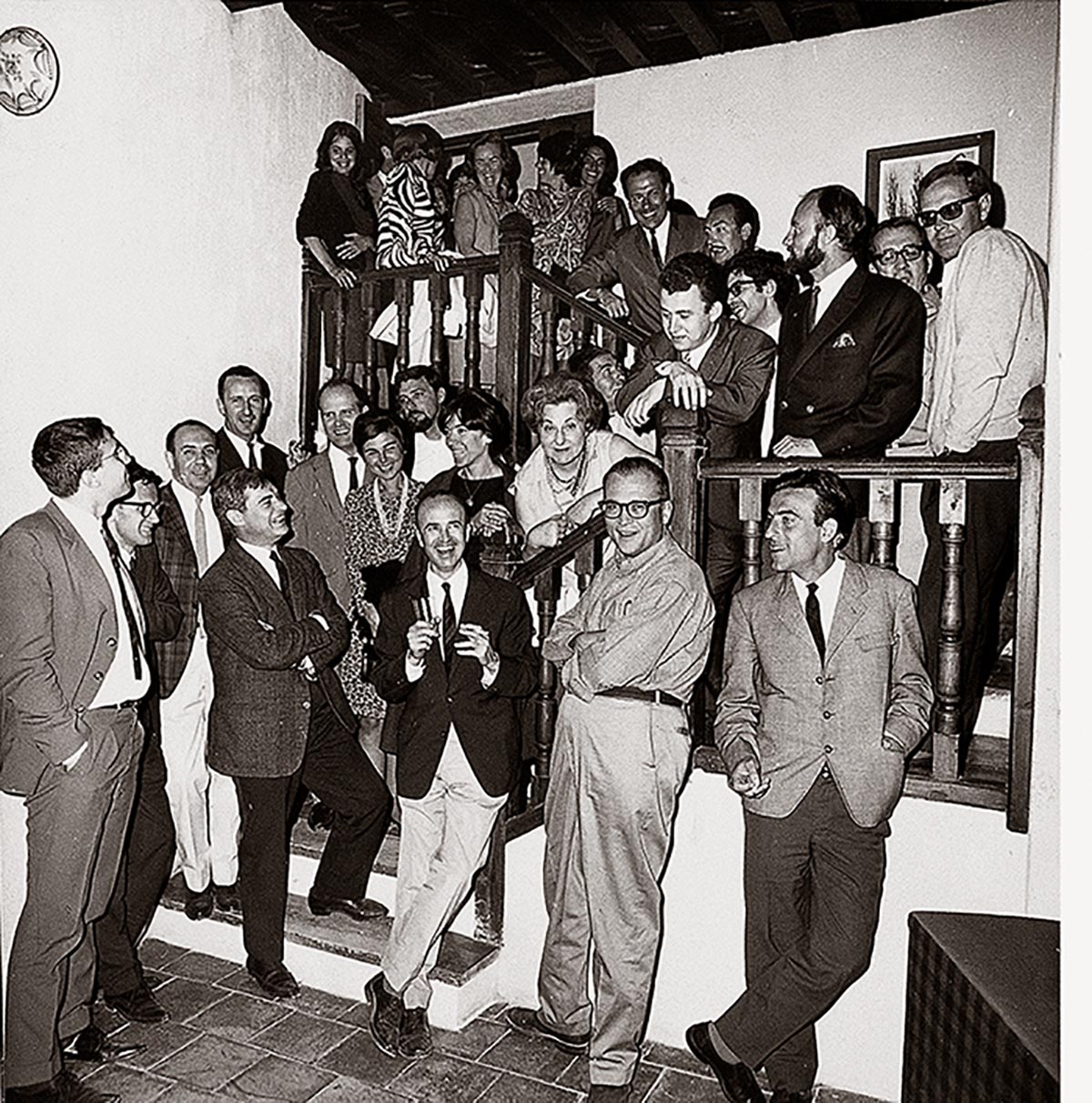

“Simple inauguration: Governor, Mayor, the President of the Council, Rodrigo Lozano de la Fuente, Fernando Nicolás and some local newspapermen. I asked Rodrigo to open the door (visibly shaken, surprise and delight), which he did with considerable difficulty, using the big iron key decorated with a purple ribbon. The museum looked beautiful, everything apparently in place. The officials were delighted. We had a cordial and very late dinner, full of ponderous compliments. My feet had swollen and throbbed. I slept like a log. The morning at the museum was quiet. We taped an interview for radio and T.V. The Edurnes came from Madrid and mainly we just sat around, chatting, occasionally going to listen to the comments of the sprinkling of visitors. I had invited nobody, on purpose, so that nobody could claim later on that they had been left out. Therefore, the groups that arrived from Madrid in the afternoon came simply because they felt like coming. There were almost fifty for dinner: Juana Mordó and, of course, the Edurnes, Manuel and Mari Rivera, Manolo and Elvireta Millares, Carmen Laffón, up from Seville, Jaime Burguillos, a sprinkling of Ruiz de la Prada brothers, Lucio Muñoz and Amalia Avia, Paco López Hernández, Antonio and Margarita Lorenzo, the Paluzzis with a young girl painter from Chicago, very attractive in a yellow shawl and a Cordovan hat, Martín Chirino and his wife, Alberto Portera and his wife, Isabel Bennet, Eusebio Sempere, Macua, Fernando Nuño, Gerardo and so on and so on. Nuño took a great photograph of the whole group, festooned along the stairway. The group’s visit to the museum was a great success.”

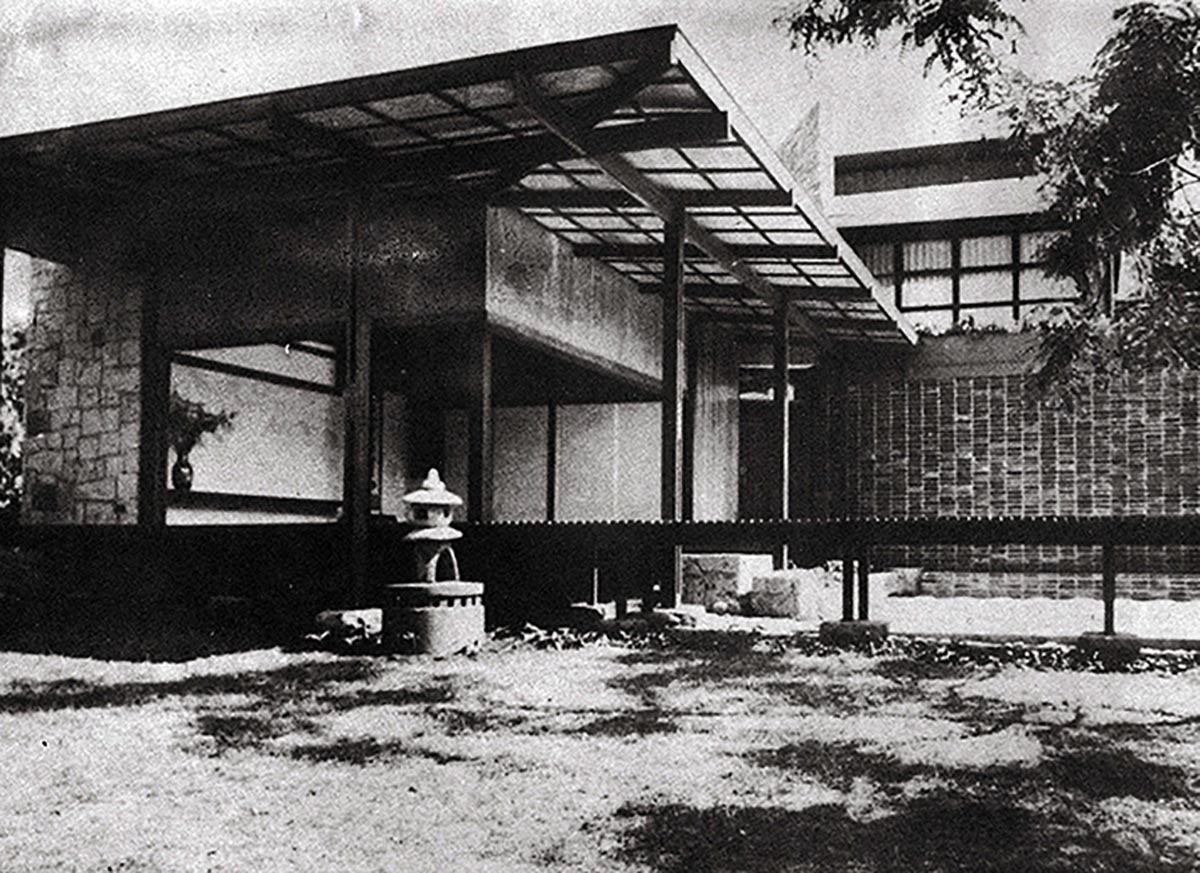

Casas Colgadas (Cuenca), where the Museum of Spanish Abstract Art is located

Casas Colgadas (Cuenca), where the Museum of Spanish Abstract Art is located

1966 Inauguration of the Museum of Spanish Abstract Art in Cuenca, June 30.

Inauguration of the Museum of Spanish Abstract Art in Cuenca, June 30.

From left to right, front row: José María Yturralde, Jordi Teixidor, Salvador Victoria, Eusebio Sempere, Fernando Zóbel and Jaime Burguillos. Back: Gustavo Torner, Lucio Muñoz, López Hernández, Carmen Laffón, Amalia Avia, Juana Mordó, José Guerrero, Nicolás Sahuquillo, Manuel Millares, Gerardo Rueda, Martín Chirino, Alberto Portera and Manuel Rivera.

Photo: Fernando Nuño.

1966A catalogue is published, with an introduction by Fernando Zóbel and black and white photographs by Fernando Nuño of some of the works. On the cover of this, the first catalogue, there is a photograph of the “Hanging Houses” at night. In 1973, Ricard Giralt-Miracle designs a dust cover for the catalogue, showing a photograph of the Blassi brothers, who will work with Zóbel on most of his publishing projects. At the museum, a number of young artists play a part, including Jordi Teixidor and José María Yturralde, also Nicolás Sahuquillo and Ángel Cruz. By this time, the museum has about 100 works, 12 sculptures, about 200 drawings, engravings and posters and several books, illustrated and engraved by Spanish artists. It is not a didactic historical collection, nor is it a comprehensive representation of Spanish abstract artists. 47, firstly, becaus financial efforts have their limitations 48 and secondly, because a private collection is made in accordance with the collector’s taste and involves

“a way of seeing as opposed to chance and whim.”

Zóbel is made Member of the Order of Alfonso X the Wise for the creation of the museum and is also named Member of the Order of Isabel the Catholic.

1967

With his return to color, Zóbel starts to produces series of paintings, and one of the first to appear in this new stage is Diálogos, dialogues with paintings, the conversations he has, pencil, pen or brush in hand, with works by other artists. In the main, these conversations take place during his trips, at museums and exhibitions, and are always recorded in some way in his notebooks. They reflect the world surrounding the painter. The works of other artists become a subject for study, for he never copies but contemplates, analyses, interprets, disarranges and rearranges so as to build in his own way (light, movement, color, gesture, intention). During an interview several years later, he explains the significance of this series within his work:

“I think this series will last all my life, until the day I depart this world. The idea behind Diálogos is to speak of art with art, but with the brushes at the ready. I stand before a picture I like and I prefer to communicate with that work by painting too. It’s a way of seeing and doing painting and will become a constant in my life, because it’s a pleasure and I see no reason to stop practising it… When “I speak” in these dialogues, I concentrate on one facet and the result is not an imitation but a comment. In plagiarism, more often than not, it’s the style that’s imitated and when I establish one of these dialogues, I can’t remember a single instance where the other painter’s style has been the subject of the dialogue.” 49

His interlocutors are many: Braque, Morandi, Rembrandt, Lotto, Poussin, Tintoretto, Adriaen Coorte, Saenredam, John Singer Sargent, Bonnard, Turner, Monet, etc. With each of them, the conversation is different. For instance, with Degas and Manet, the topic of conversation will be color; with Turner and Monet, chromatic values. About Tintoretto, with whom he holds several dialogues, there are countless drawings throughout his notebooks. When writing of the St. George in London’s National Gallery, he says:

“Each goes his own way: he expands and contracts like a boa constrictor’s poison gland. The unquestionable ‘s’ in raspberry pink, a cloak echoing into a cloud. An ‘S’ that is always pulled in opposite directions, along a staircase of horizontal movements. The saint throws himself upon the dragon (later to be stolen by Gustav Doré), which will inevitably send him rolling down to the water, together with his cardboard horse. With his lance, he presses a spring to release that well-fed virgin in a gesture somewhere between dread and that of a chubby angel bearing tidings of glory. The body, for instance, might serve to reinforce the diagonal movement and the obedient tree finishes it off. In all of Tintoretto’s work, there are a couple of superposed pictures; at times, they are even contradictory. Here, the theme is not convincing, the gestures even less. The gesture, however, is. I’m referring to the gesture of the painter. And it’s a strange picture – and part of any. It is no mean task to give life to a series of horizontals. It’s rather like trying to destroy a commonplace. Kandinsky, who sought to convert his collection of commonplaces into language, would have objected to this series of rebel horizontals and illogical colors (the warm ones marking out the distance within the cold ones). A dialogue in three steps crossing the whole picture (three squares), starting with the Christ and finishing with the water vanishing to the left. Contained within an oval frame, but it is precisely inside the frame that action takes place. The viewer does not stand IN FRONT, he goes round and comes in from the back. It’s a bit like a picture turned back to front. As if we’d been allowed in with a special pass provided by someone with connections. The plebs – invisible – remain on the outside, in the area of the classical arch.”50

The opening of the Museo de Arte Abstracto Español draws the international press and, around this time, many articles about the museum are published (Time Magazine, Architectural Forum, Herald Tribune, Studio International, London Telegraph, Gazette des Beaux Arts, etc.). The museum is visited frequently by specialists, curators and artists. Of particular note is the visit of Alfred H. Barr, the first director of New York’s Museum of Modern Art (MoMA). On January 1 1967, Zóbel writes the following about Barr’s visit:

“More visitors: Carlos and Charo Reim, Javier Reim, Teixidor with girlfriend, Yturralde with wife and baby. Around noon, Jean Bratton turned up with Alfred Barr from the Museum of Modern Art and his wife. Quiet, elderly, very charming and intelligent. (…) Barr saw the place slowly, taking notes. At the end, he asked if he had time for a second round. He did, so he started again at the beginning and repeated the whole tour. Lunch at Sempere’s. Barr leaned over and whispered that he and his wife thought it the most beautiful museum they had ever seen. I asked him if he would repeat that. He said yes, and repeated it aloud. The crowd cheered and we made him honorary curator on the spot. More singing, dancing and so on. The Barrs were obviously enthralled. Barr asked me to help review their Spanish collections at the MoMA. I offered to help fill the gaps.”

From this year onwards, Rafael Pérez-Madero will work alongside Fernando Zóbel as secretary, administrator and assistant in all the projects concerning his work and the museum. In addition to working on a publication about his painting, La Serie Blanca, and a short about his work, after his death, he took over management of his work and organized most of the exhibitions, including this one.

Lecture on the two currents of Spanish abstract art, Las dos corrientes del arte abstracto español, at Cuenca’s Casa de Cultura.

1968

Individual exhibition at the Bertha Schaefer Gallery, New York.

At the end of the sixties, Zóbel’s work grows more geometric while, generally speaking, his style becomes colder. In this sense, it reflects the harshness noticeable in nearly all the artistic currents of this decade. In these works, spaces are built by means of lines drawn in pencil, broken lines and impeccable perspectives. Trapeziums, rhombuses and cubes articulate the composition by means of an architectural framework. Series on themes relating to Cuenca start to appear – La fuente, La calle estrecha –, themes alluding to Seville – Conde Ibarra – and themes from classical painting, such as the six dialogues with Pieter Saenredam (1968) and the seven conversations with painter Adriaen Coorte (1968). The essence lies in the practice of developing a theme gradually by means of lots of pictures, drawings, sketches and photographs.

After Zóbel’s exhibition at Seville’s Galería La Pasarela the year before, this city starts to form part of his life. In Seville, he becomes a very close friend of painter Carmen Laffón, with whom and José Soto he shares a studio. Also around this time, he strikes up a friendship with the Bonet Correa family and painters Joaquín Sáenz and Gerardo Delgado.

Munich, Photograph by Cristobal Hara

Munich, Photograph by Cristobal Hara

19681969

First photography exhibition, Cuenca y sus niños at Cuenca’s Casa de Cultura.

A year of intense travelling: New York, Washington and Boston; Teruel and Albarracín; London; Munich and Geneva.

He writes a text about Antonio Lorenzo, titled, Lorenzo. Machines for the imagination, appearing in the catalogue for the exhibition of this artist’s work at the Galería Kreisler

NOTES

31. Father Miguel A. Bernard, a great friend of Zóbel’s from Manila, recalled the matter: “There was an amusing incident when we first got Fernando Zóbel to lecture in the Ateneo Graduate School. The Dean of Graduate Studies asked him to give a quick lecture, followed by a period for questions and discussion. Zóbel’s first question was: ‘How much do you pay?’ This was a disconcerting question coming from Fernando Zóbel. The dean said: ‘Thirty pesos an hour, sixty for the two-hour period.’ Zóbel replied: ‘That is respectable.’ But at the end of each term, he would take this cheque, endorse it, give it back and say: ‘Use this money to buy reproductions of famous paintings. Have them framed and charge the cost of the framing to me.” Miguel A. Bernard, “Fernando Zóbel, an artist and scholar. 1924-1984”, Kinaadman, vol. VII, 1, Manila, 1985, p. 53.

32. In the notebook “F.Z.A. 1958-1959”, p. 51.

33. As the years go by, Zóbel continues to give his support to these artists through gestures like the one he showed when his nephew, Jaime Zóbel de Ayala, was the Philippine ambassador in London: he gave him an important collection of works by Philippine painters, to be put on show at the embassy, thus indirectly disseminating their work abroad. Vid. Armando Manalo, “Fernando Zóbel. A virtuoso of paint”, Pace, Manila, March 24, 1972.

34. In Philippine Studies, Vol. IX, nº 19, Manila, 1961.

35. The Spanish Pavilion, selected by Luis González Robles, included works by painters such as Vicente Vela, Rafael Canogar, Juan Genovés, Hernández Mompó, Guinovart and Zóbel, amongst others.

36. This exhibition showed landscapes belonging to the Song Dynasty (tenth to thirteenth centuries), paintings by erudite members of the Qing Dynasty (1644-1911) and works by painters Fan Guang (eleventh century) and Xu Daoning, from the Northern Song Dynasty.

37. Fernando Zóbel, Chicago, March 1 1962.

38. Vid. Rafael Pérez-Madero. Zóbel. Obra gráfica completa. Cuenca, 1999, p. 13.

39. Antonio Lorenzo and José J. Bakedano: Catálogo exposición Antonio Lorenzo. Obra gráfica (1959-1992), Museo de Bellas Artes de Bilbao, Bilbao, 1992.

40. Fernando Zóbel, November 29 1962.

41. ““I collect my Prado copier’s card (nº. 342). The main thing is that it entitles me to a chair. I’d almost finished the pictures that happened to have a chair opposite. Drawing the pictures is a way of seeing them. It cleanses the eyes and leaves the most unexpected things in the subconscious.”

Fernando Zóbel, Madrid, August 21 1962.

42. Fernando Zóbel, Madrid, October 29 1964.

43. Madrid, 1963. 96 pages, 27 plates in black and white, edition of 999 numbered copies. The text has been translated into English and French. All the copies are stamped onto handmade linen paper of the varieties Ingres and Castell, produced by Guarro, Barcelona.

44. “Chillida, who came to Cuenca with his wife, invited by Saura, was also younger than I thought. (…) Direct, friendly, obviously intelligent and very well-informed. (…) Chillida loves Greece. He spoke on and on. He feels their art (he kept using the adjective, noble; a good indication of the sort of thing he is after himself) is a direct consequence of the quality of light (if the light has the quality, why has the art it produces dried up for two thousand years?). He enthused over the museum.I asked him to do one of his wooden things for the first landing.”

Fernando Zóbel, Cuenca, May 1964.

45. Chillida could not answer him during their first encounter because, initially, this piece had been allocated to the Houston Fine Arts Museum, which finally bought the first and last of the Abesti Gogora series, both of which were executed in granite.

46. “Rueda”, The Chronicle Magazine, Vol. XIX, nº 8, Manila, February 22 1964.

47. In 1966, painters represented at the museum include, amongst others, Antonio Saura and the other members of the El Paso Group, Cuixart, Tàpies, Tharrats, Millares, Chillida, José Guerrero, Lucio Muñoz, Antonio Lorenzo, Gerardo Rueda, Gustavo Torner, Sempere, Néstor Basterrechea, José María Labra and Zóbel.

48. Although Zóbel’s financial resources were solid, the effort deployed during this period was considerable. To cope with the great expense involved in opening the museum (frames, lighting, books for the library, furniture and fittings, personnel, maintenance and so on), Zóbel sold his magnificent collection of stamps. Furthermore, we know that, during this period, he gave away several houses, paid the hospital bills of two sick friends (Agustín Albalat and Antonio Magaz Sangro) for many years; any artist in trouble who came to him for help would always find him willing; he saved a Valencian review from closure; in 1964, he donated a collection of drawings by Spanish abstract artists to the Fogg Art Museum at Harvard University, and so on and so forth.

49. In the interview, “Preguntas a… Fernando Zóbel”, conducted by Carlos García Osuna. El Imparcial, Madrid, 24 de febrero de 1978.

50. In the notebook Fernando Zóbel de Ayala. Drawings (1963-1964), pp. 51 y 53.

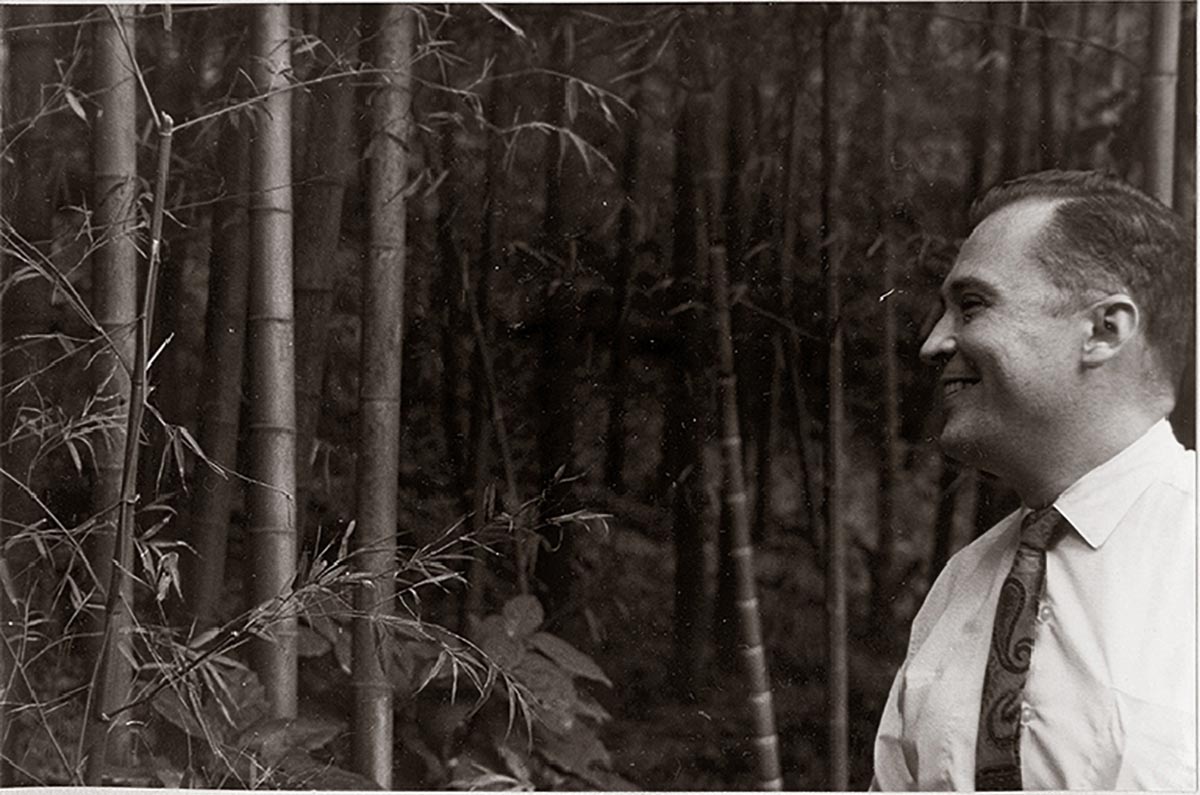

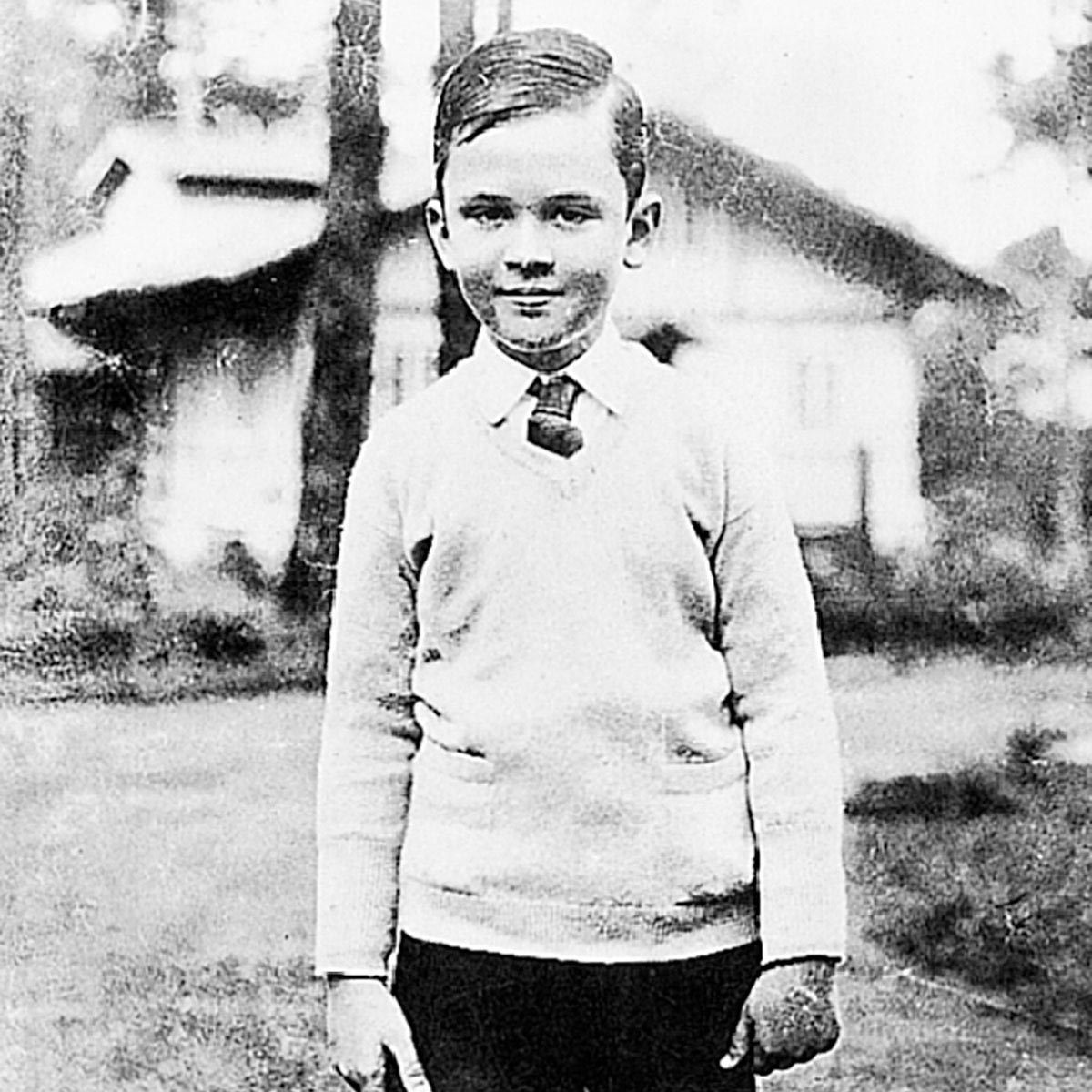

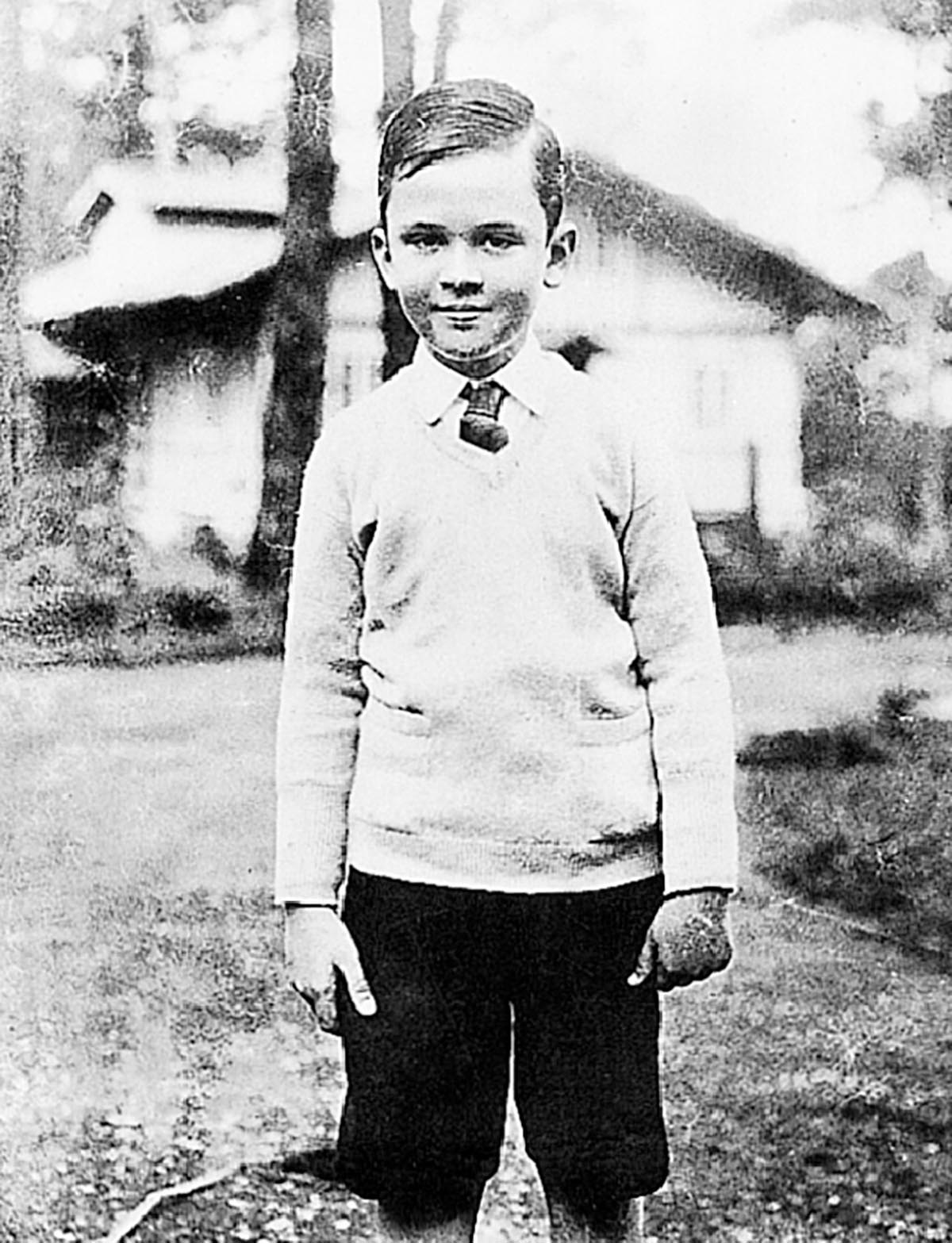

Fernando Zóbel in Baguio, Philippines.

Fernando Zóbel in Baguio, Philippines. Fernando Zóbel in Baguio, Philippines.

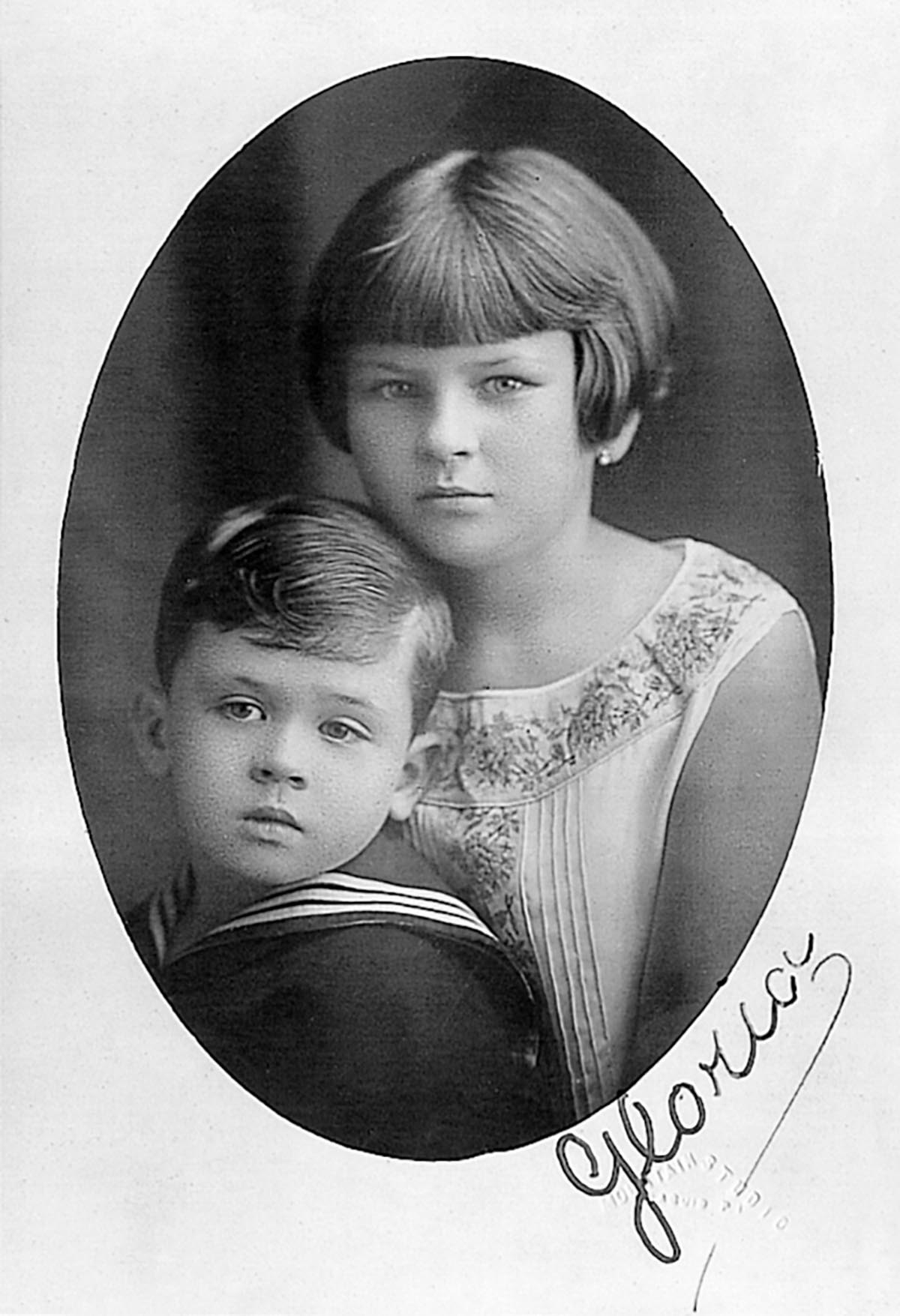

Fernando Zóbel in Baguio, Philippines.  Fernando Zóbel and his sister Gloria, Manila

Fernando Zóbel and his sister Gloria, Manila

Fernando Zóbel with his family at their home in Manila in the late 1930s (from left to right, and from bottom to top). Seated on the floor, front row: Enrique Zóbel, María Victoria Zóbel and Fernando Zóbel. Seated in armchairs, second row: Angelita Olgado, wife of Jacobo Zóbel; Doña Fermina Montojo de Zóbel, mother of Fernando Zóbel and wife of Enrique Zóbel de Ayala; Consuelo Zóbel, wife of General James D. Alger; Gloria Zóbel, wife of Ricardo Padilla y Satrústegui; Don Enrique Zóbel de Ayala, father of Fernando Zóbel; Joseph R. McMicking and his wife Mercedes Zóbel. Standing, third row: Matilde Zóbel, wife of Colonel Luis Albarracín; Jacobo Zóbel, and Alfonso Zóbel with his wife Carmen Pfitz.

Fernando Zóbel with his family at their home in Manila in the late 1930s (from left to right, and from bottom to top). Seated on the floor, front row: Enrique Zóbel, María Victoria Zóbel and Fernando Zóbel. Seated in armchairs, second row: Angelita Olgado, wife of Jacobo Zóbel; Doña Fermina Montojo de Zóbel, mother of Fernando Zóbel and wife of Enrique Zóbel de Ayala; Consuelo Zóbel, wife of General James D. Alger; Gloria Zóbel, wife of Ricardo Padilla y Satrústegui; Don Enrique Zóbel de Ayala, father of Fernando Zóbel; Joseph R. McMicking and his wife Mercedes Zóbel. Standing, third row: Matilde Zóbel, wife of Colonel Luis Albarracín; Jacobo Zóbel, and Alfonso Zóbel with his wife Carmen Pfitz.