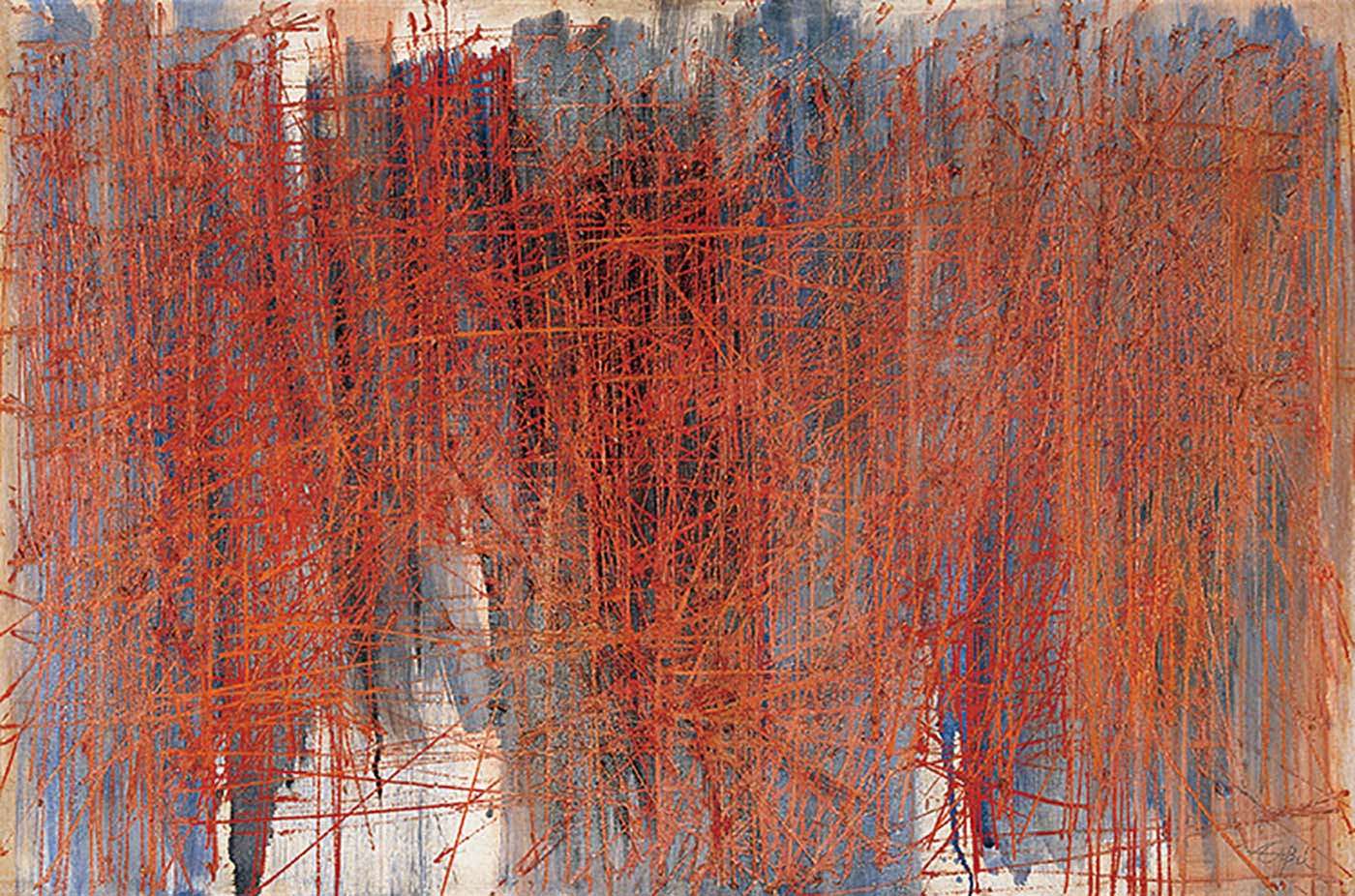

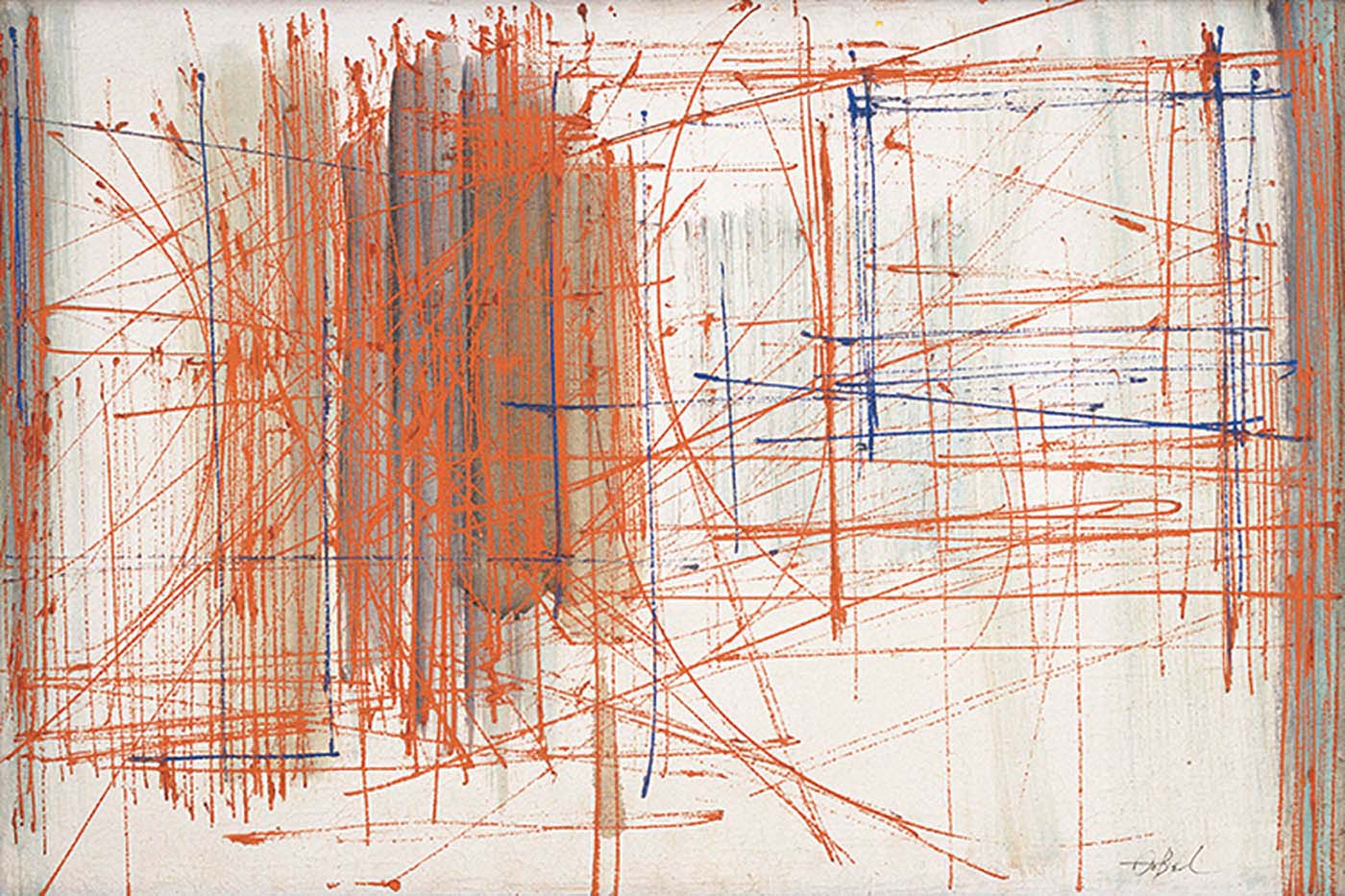

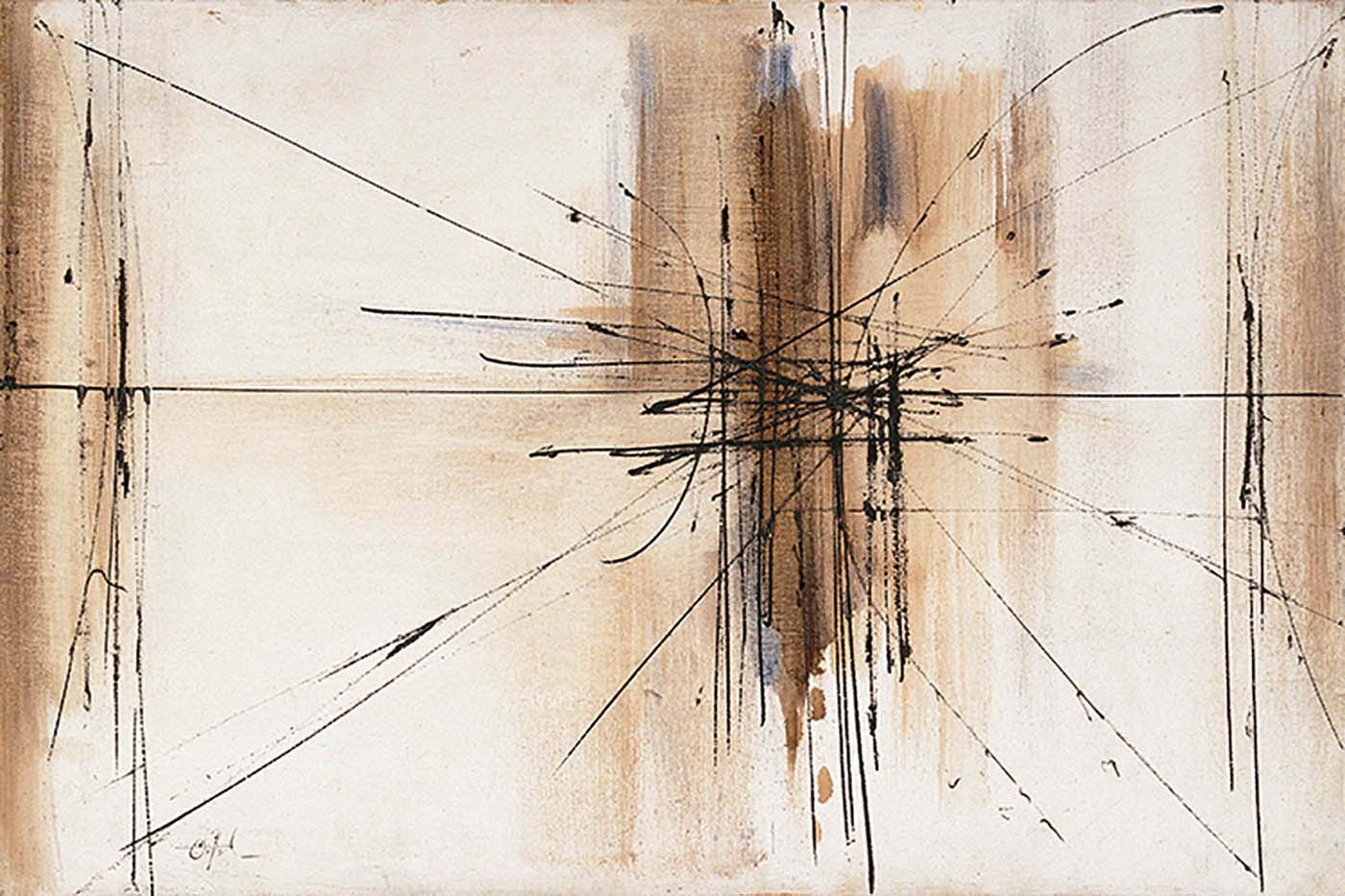

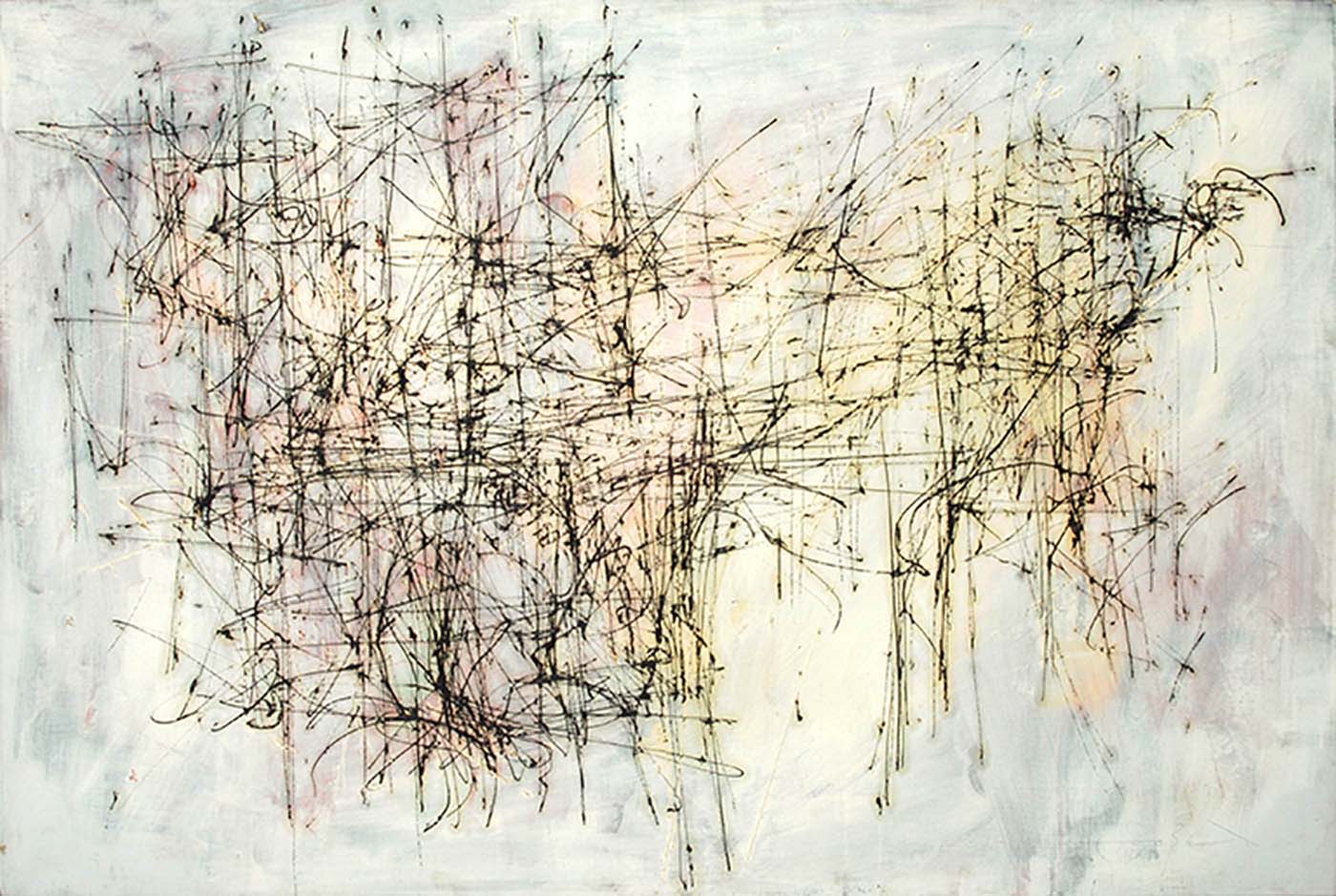

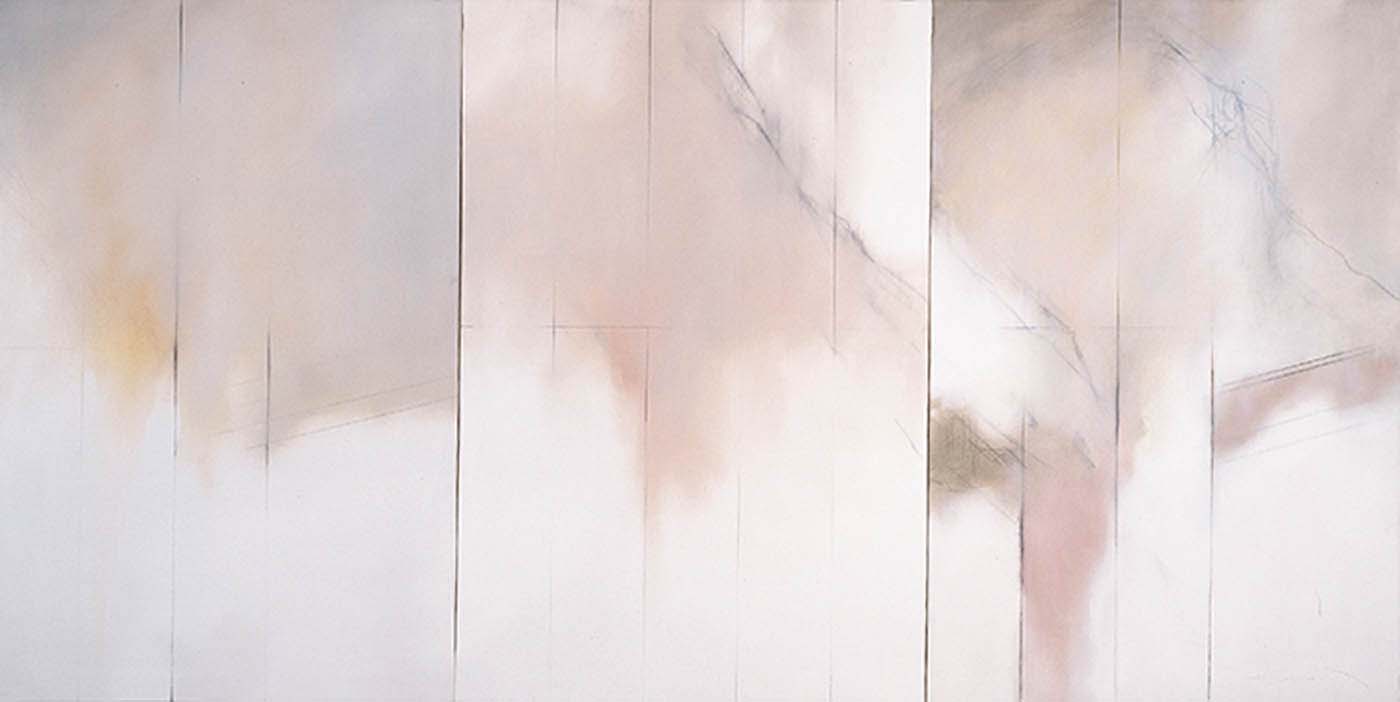

PAINTINGS

Rafael Pérez-Madero

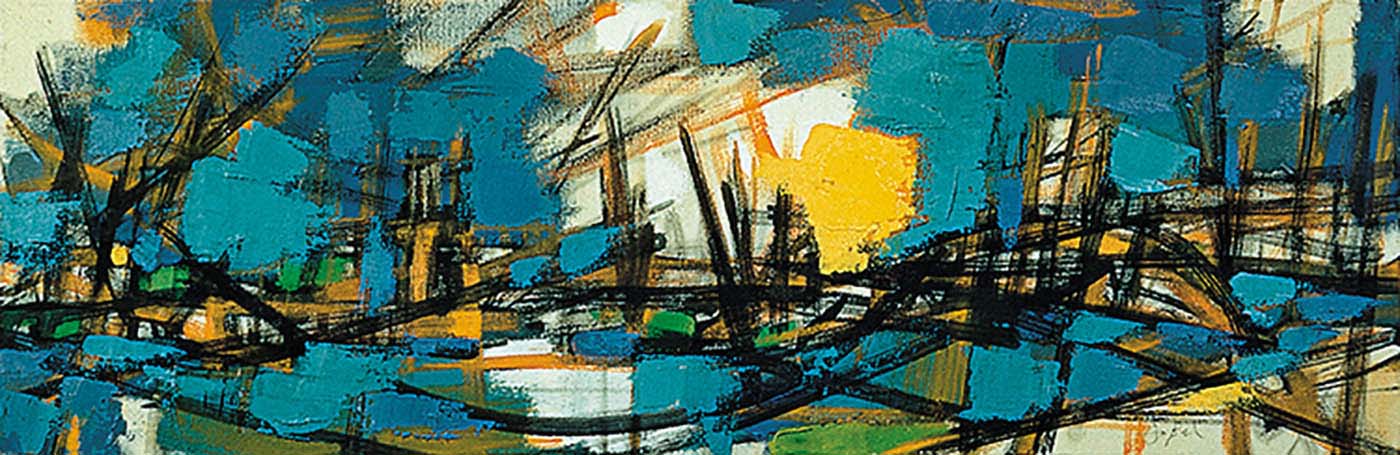

It is difficult to talk about the work of Fernando Zóbel without mentioning the many activities he carried out throughout his life, as well as the many circumstances that coincided in his person. A Spanish painter born in the Philippines, who studied high school in Spain, Switzerland and the Philippines, and received a degree and doctorate in Philosophy and Literature at Harvard University with the qualification of magna cum laude. An impenitent traveler between Europe, America and the East, Zóbel had a clear vocation to create currents and unite cultures, in addition to the multiple facets that converged in his personality and were developed by him throughout his life: historian, patron, university professor, bibliophile, collector, creator and founder of the Museum of Spanish Abstract Art in Cuenca. All these activities were endowed with a great intellectual charge which shaped his extraordinary personality, and never meant a dispersion of the character, as could have happened, but all of them were united under the common denominator of his great vocation: painting.

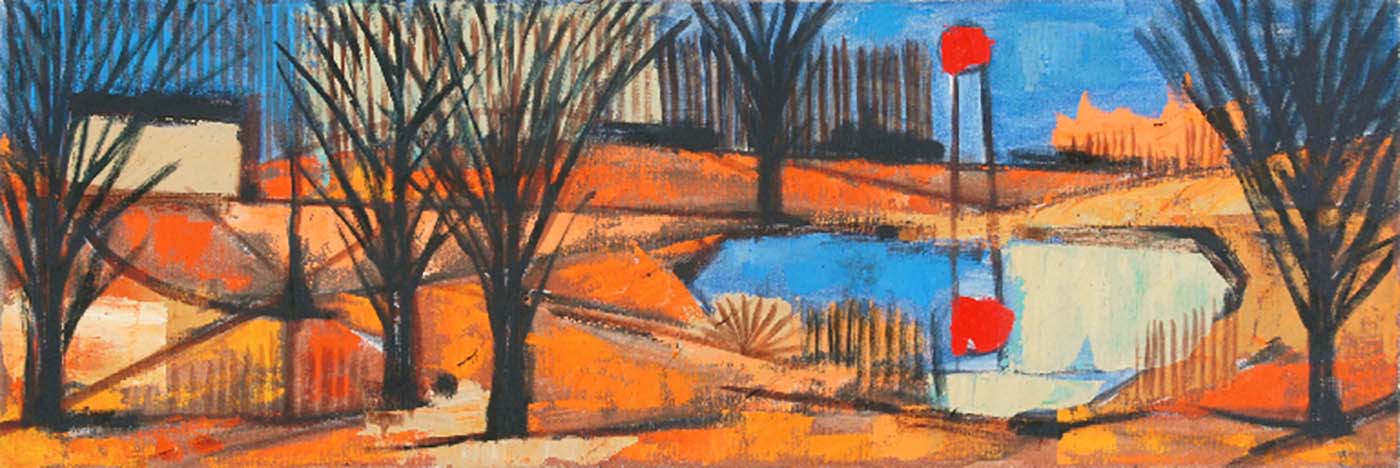

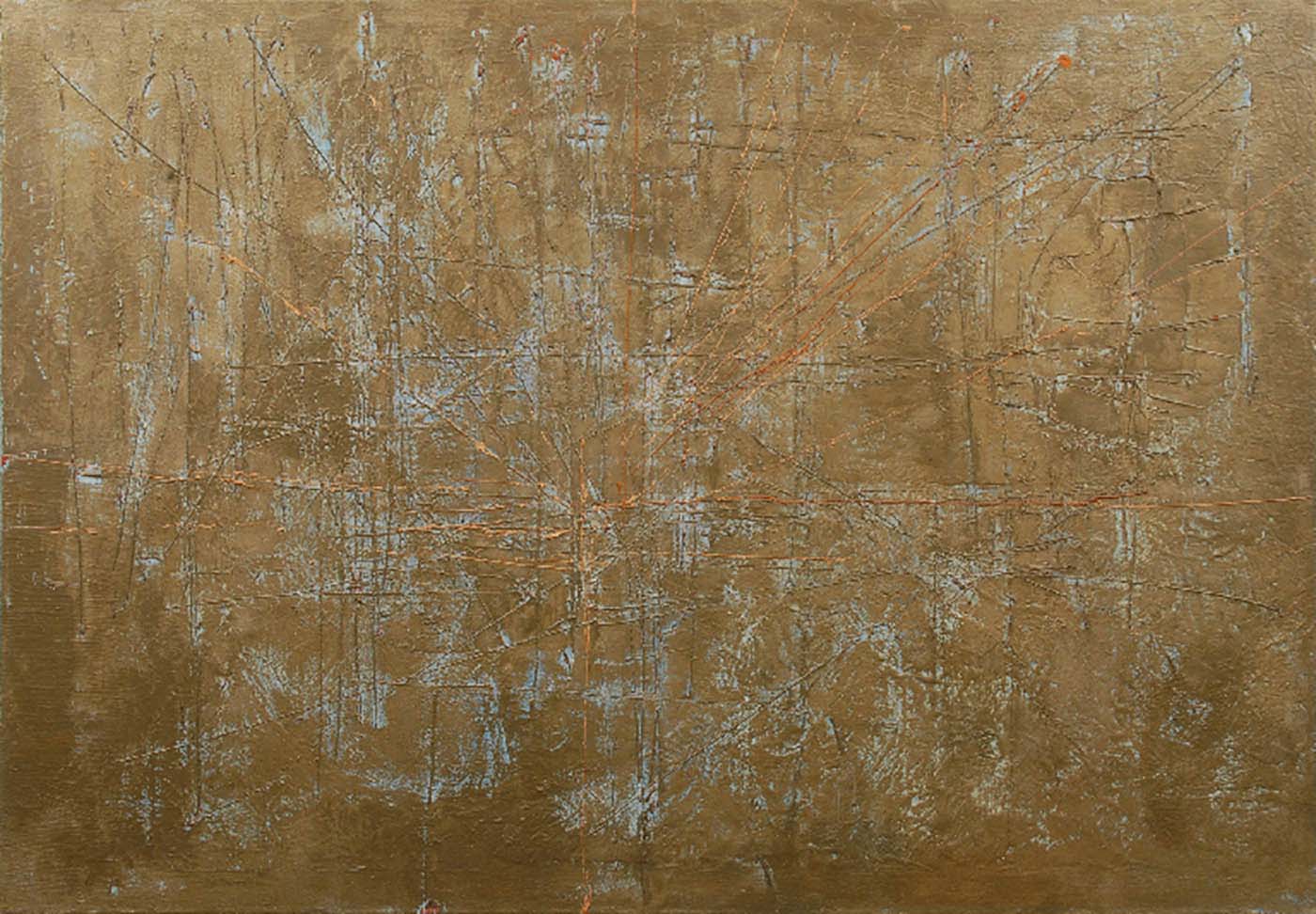

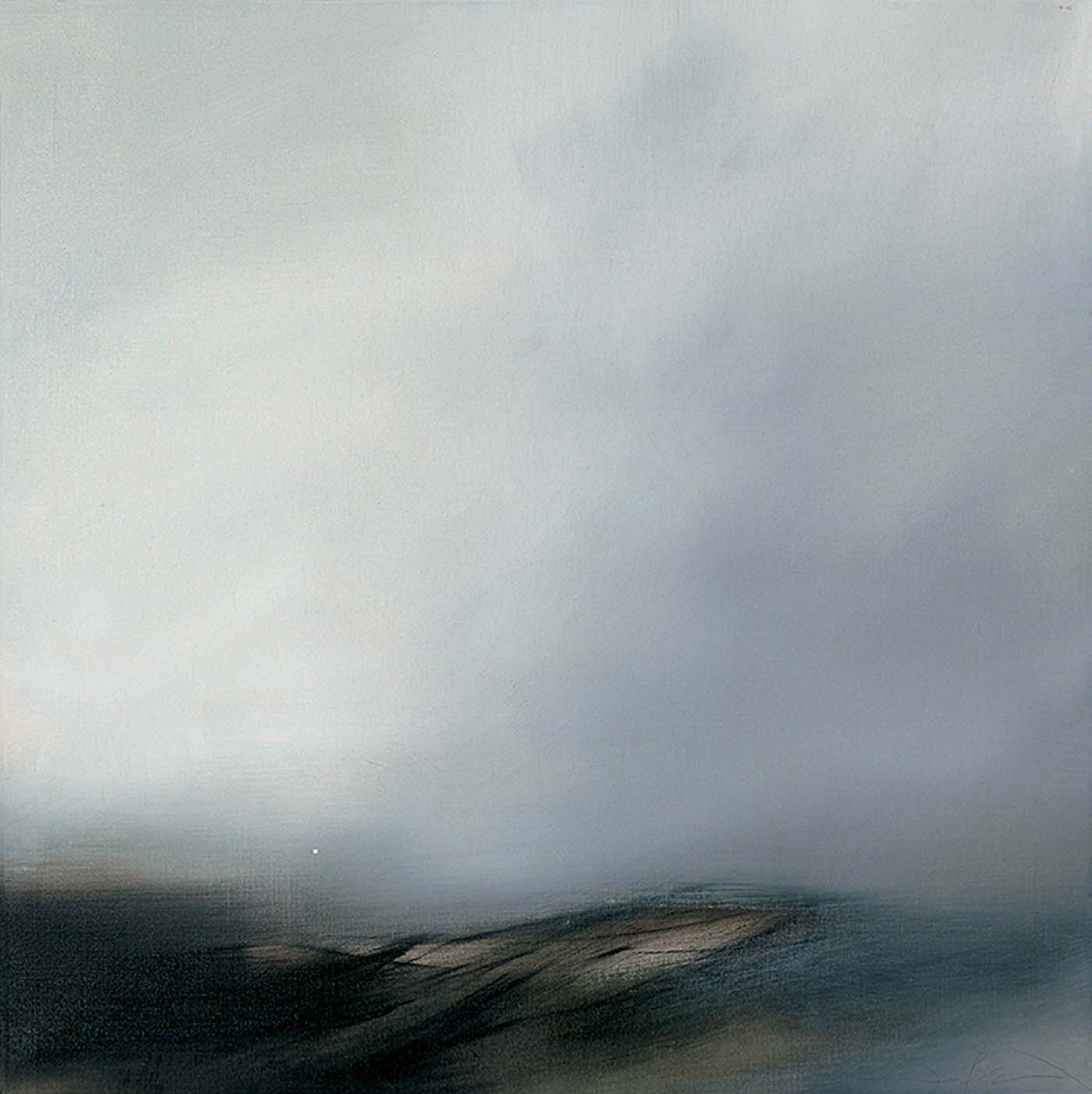

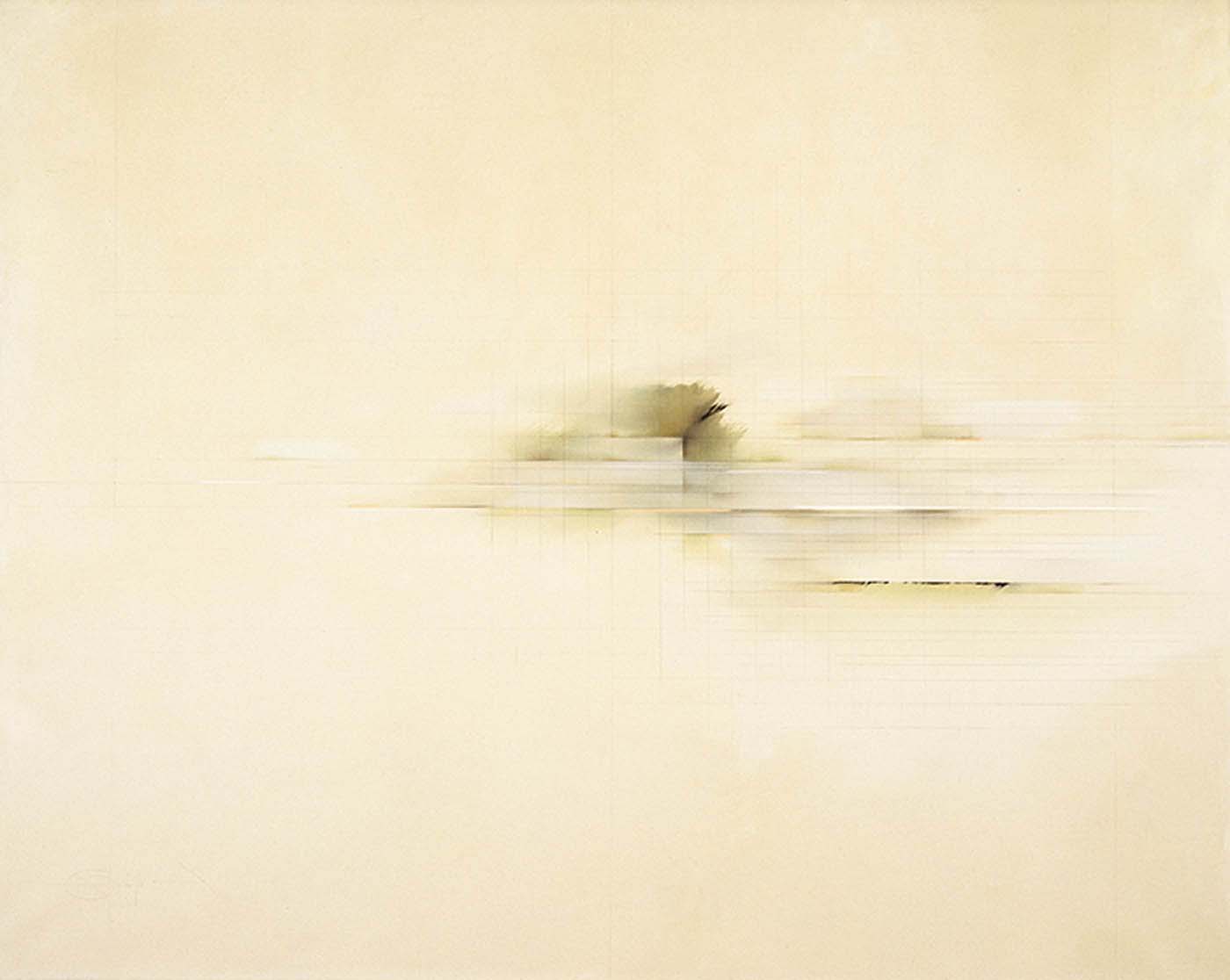

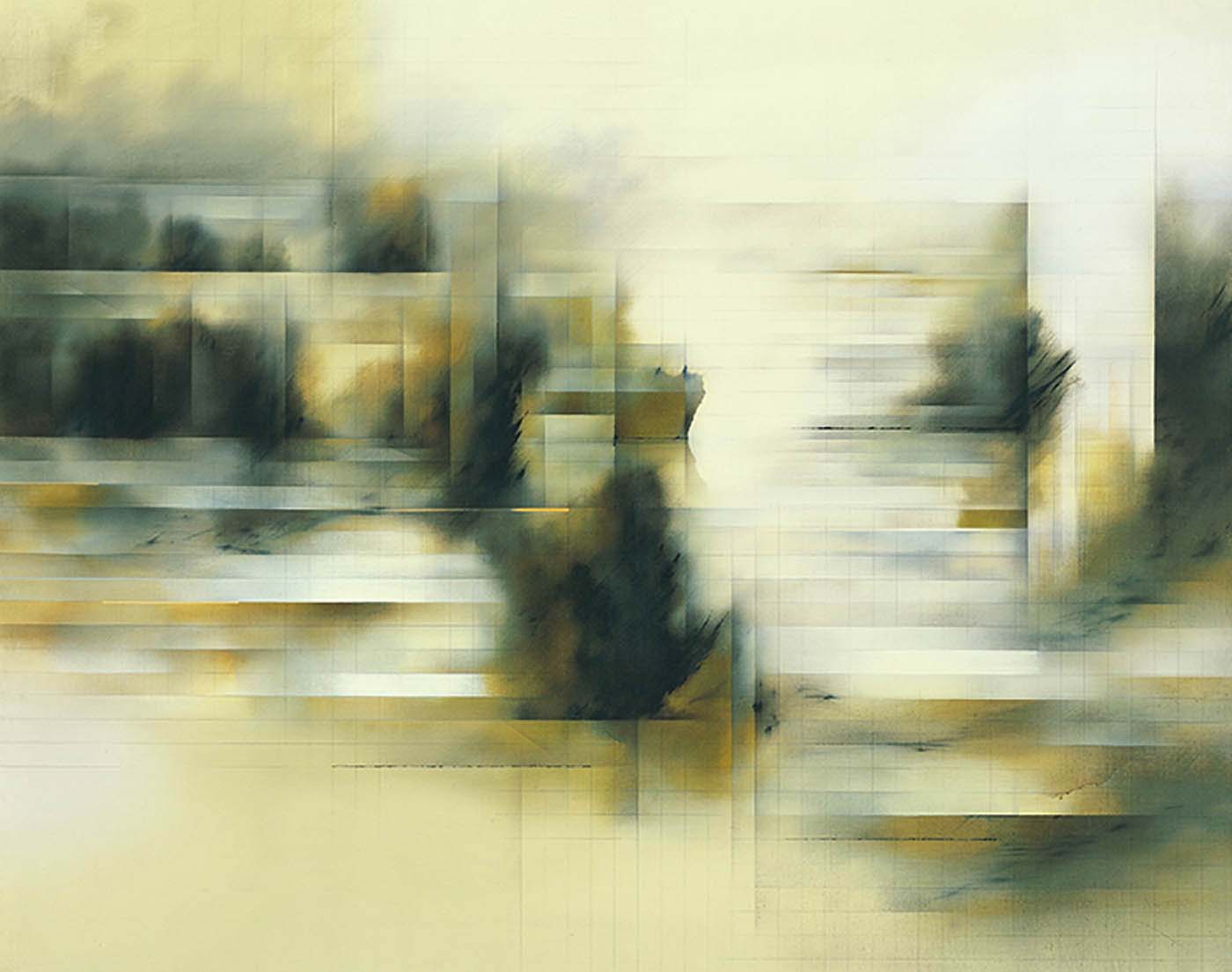

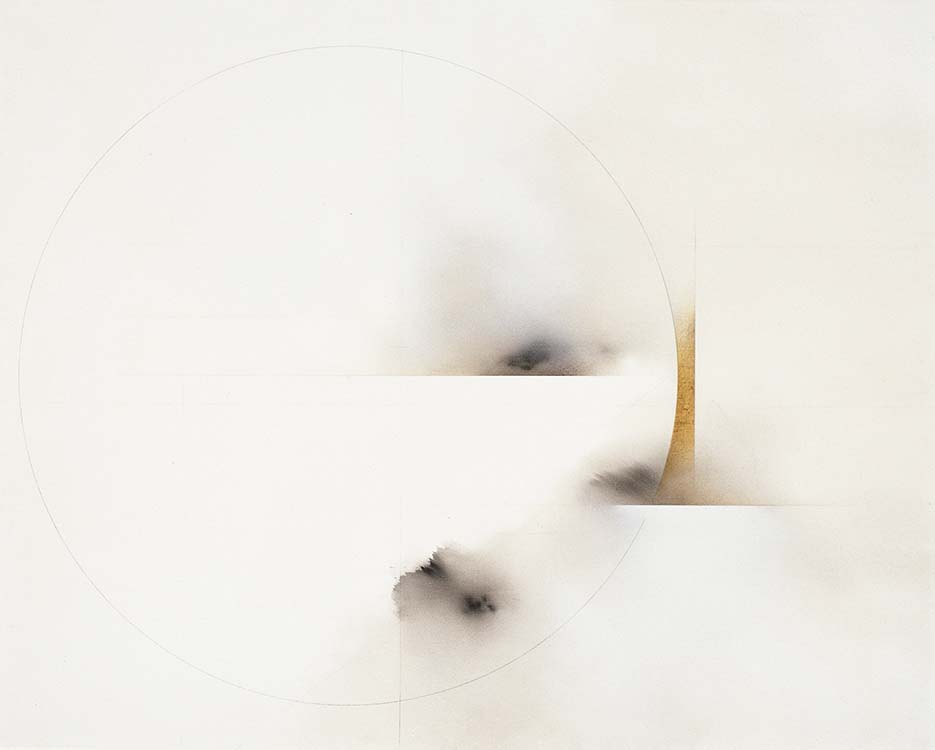

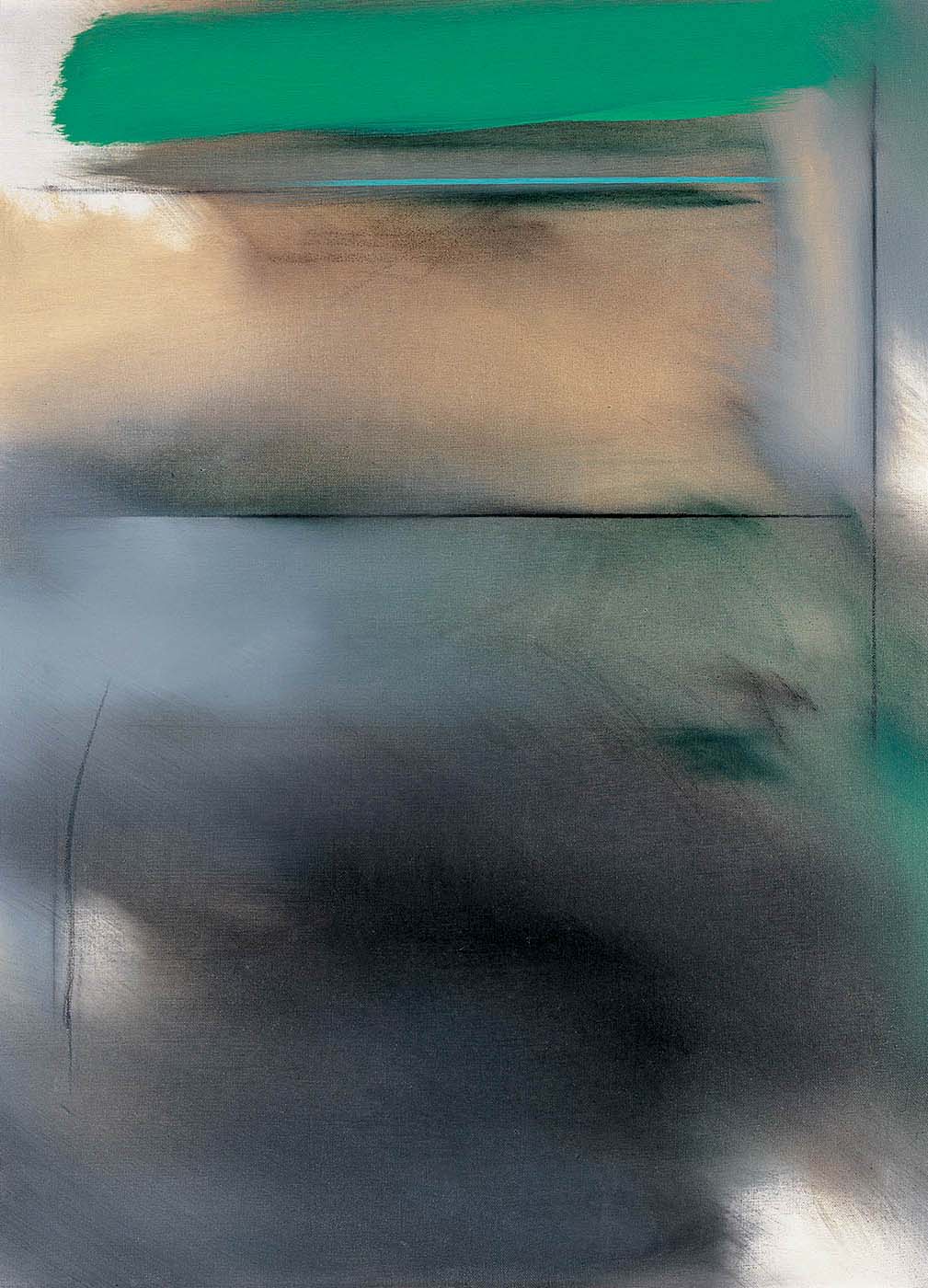

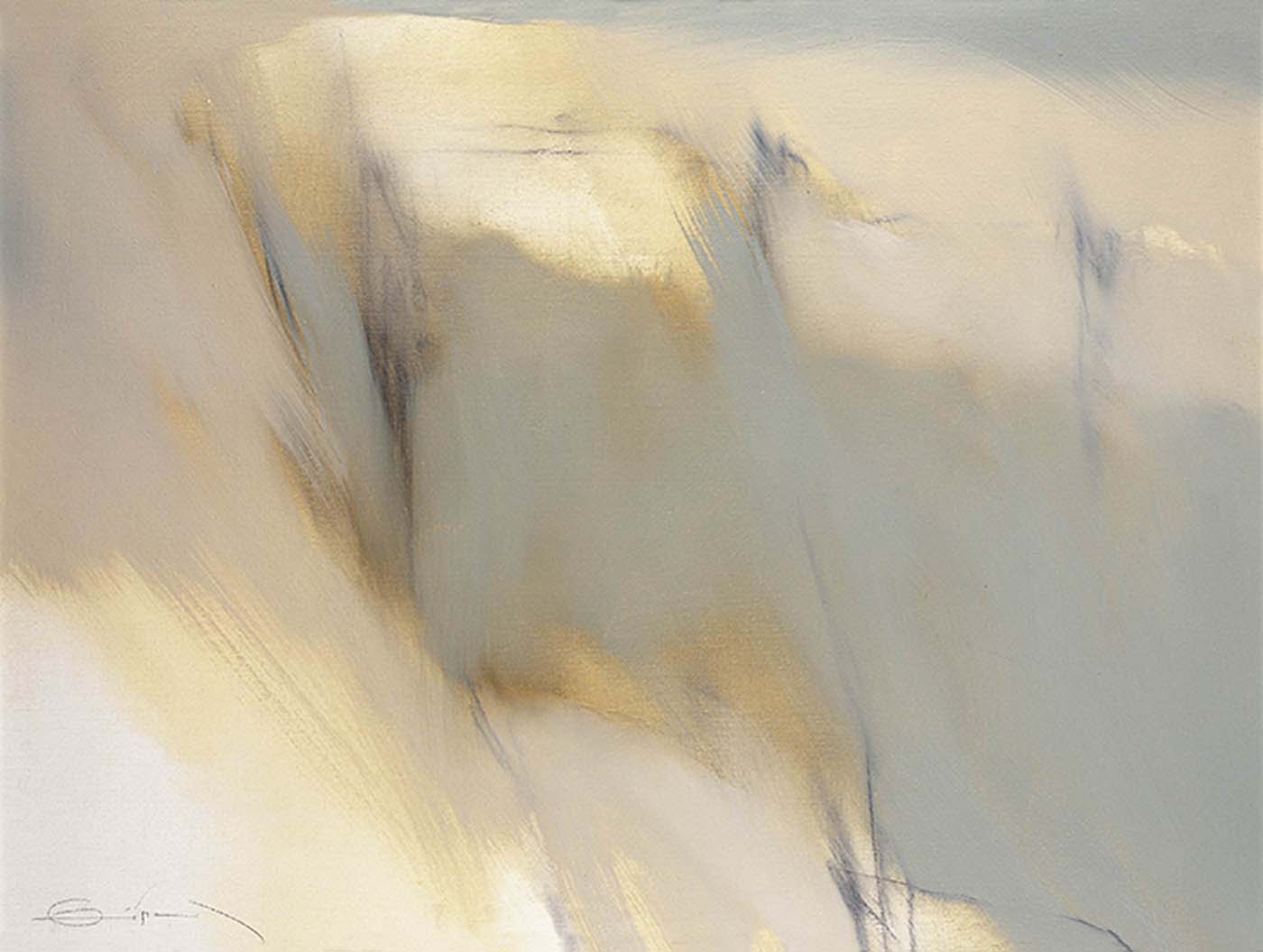

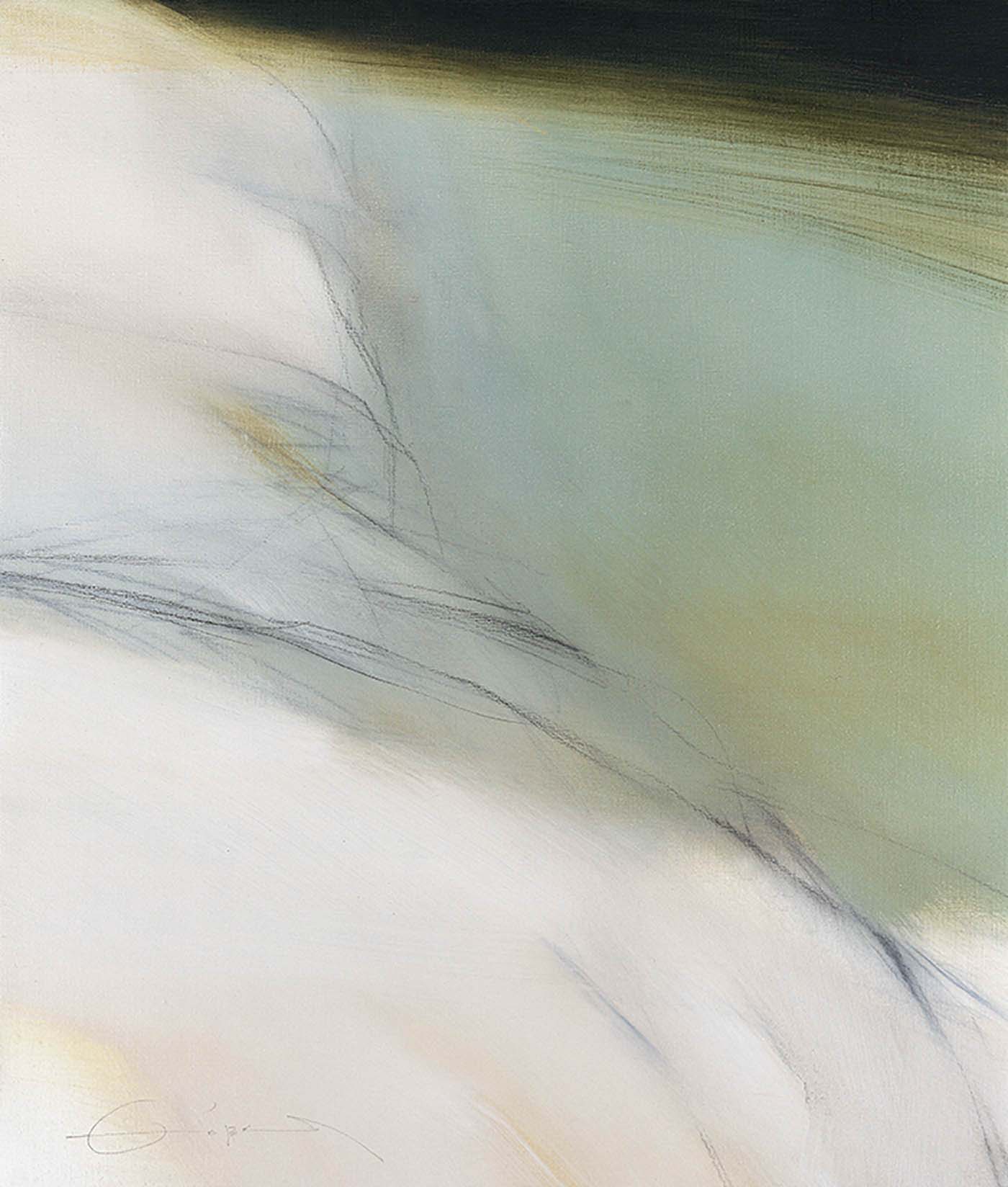

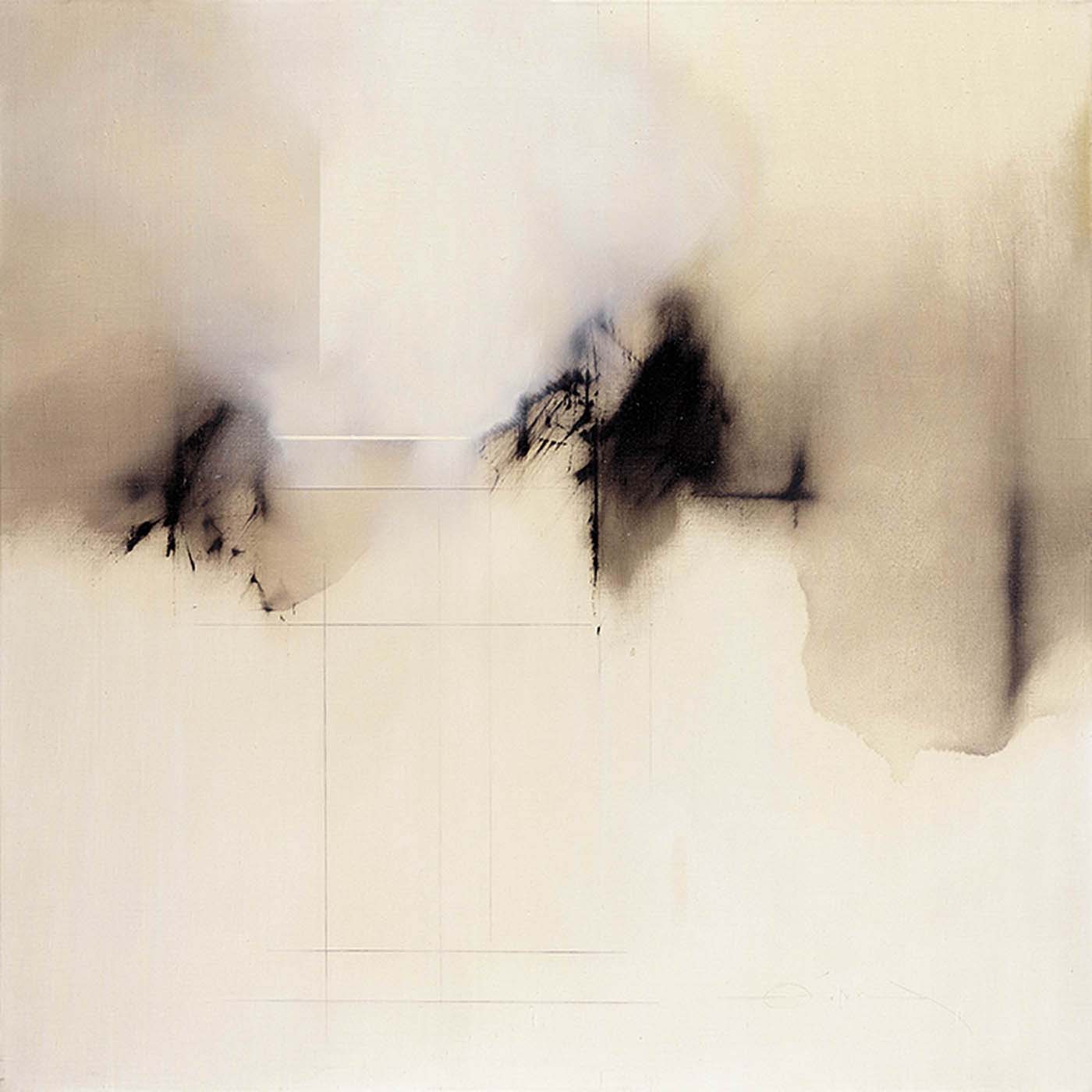

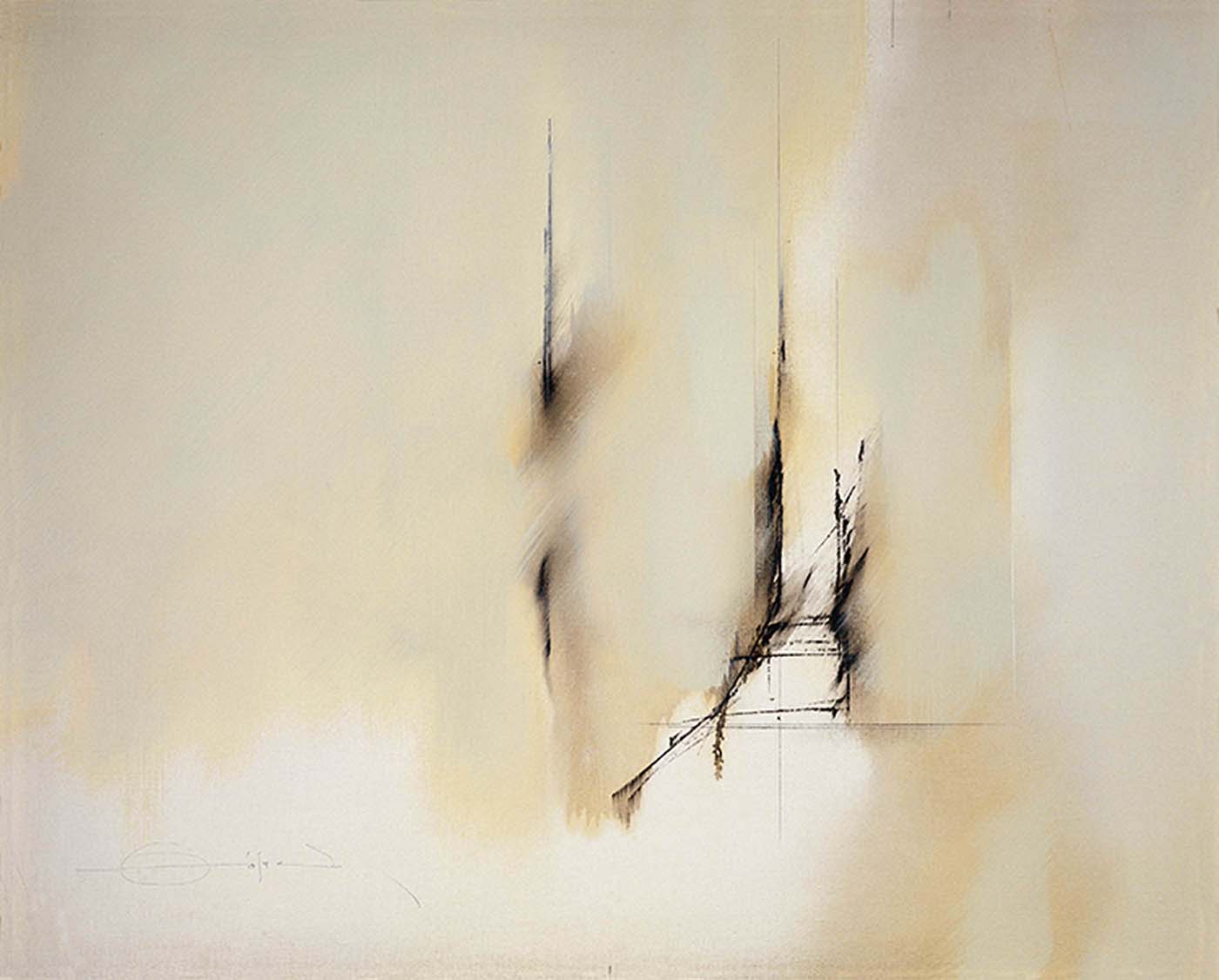

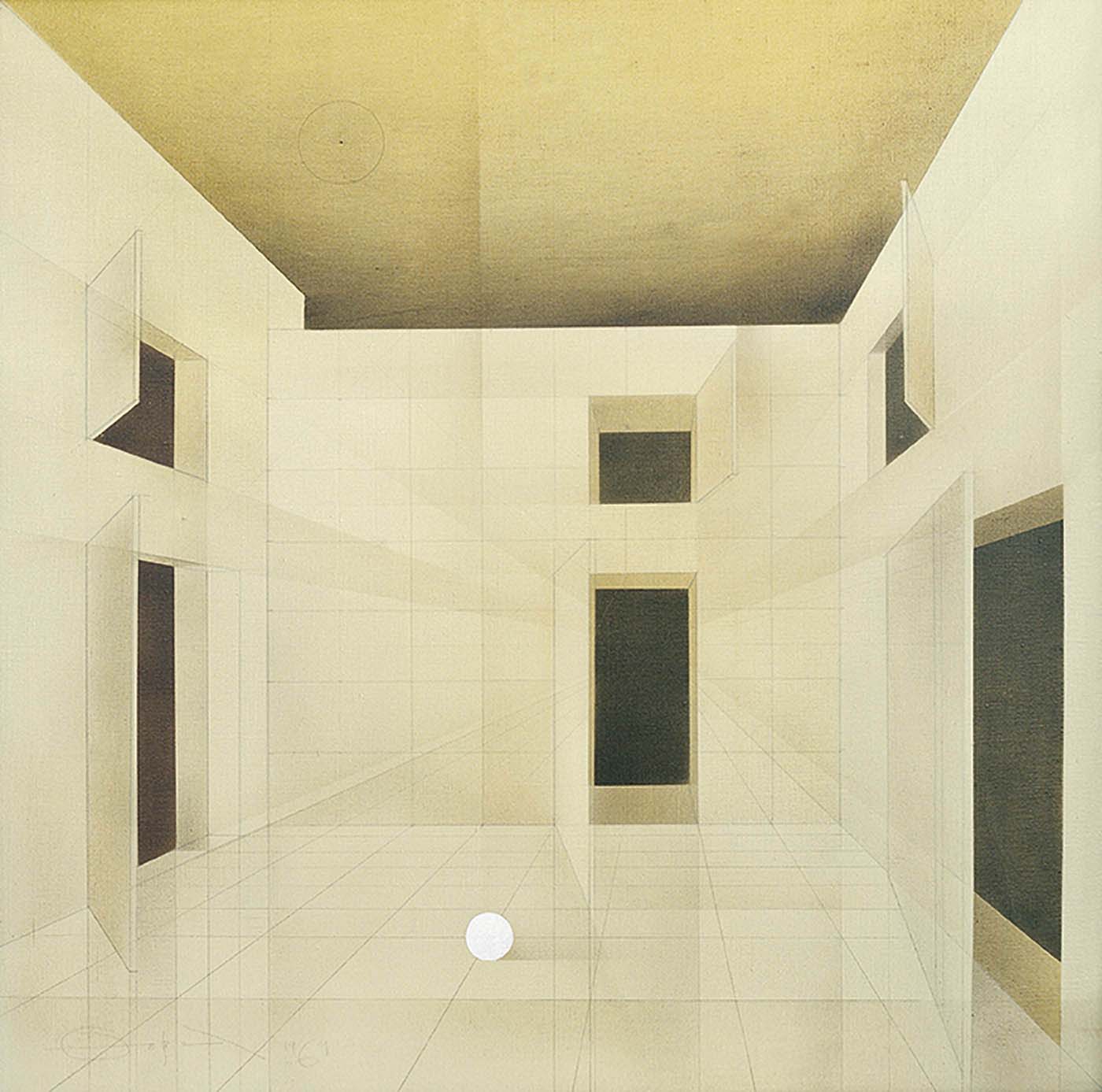

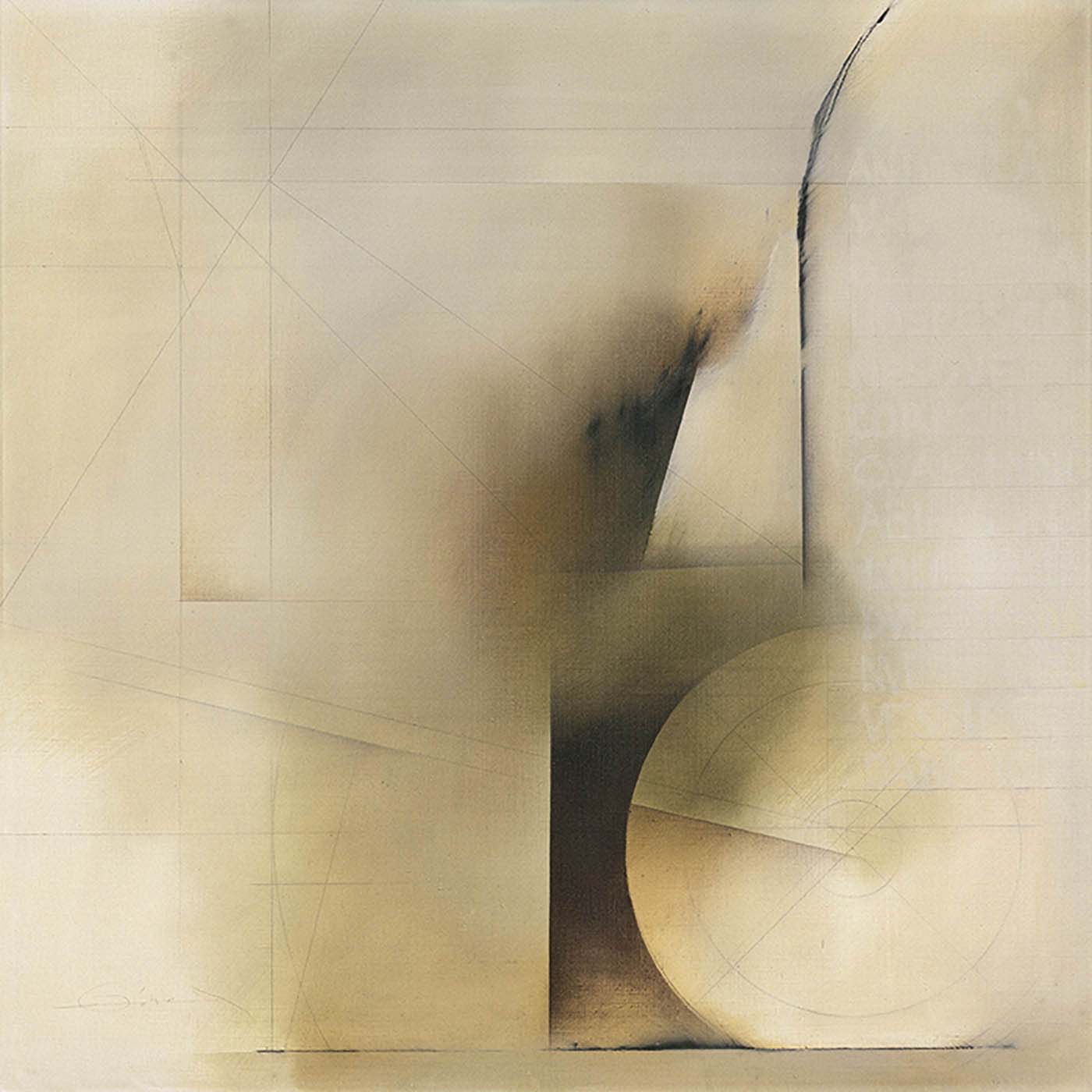

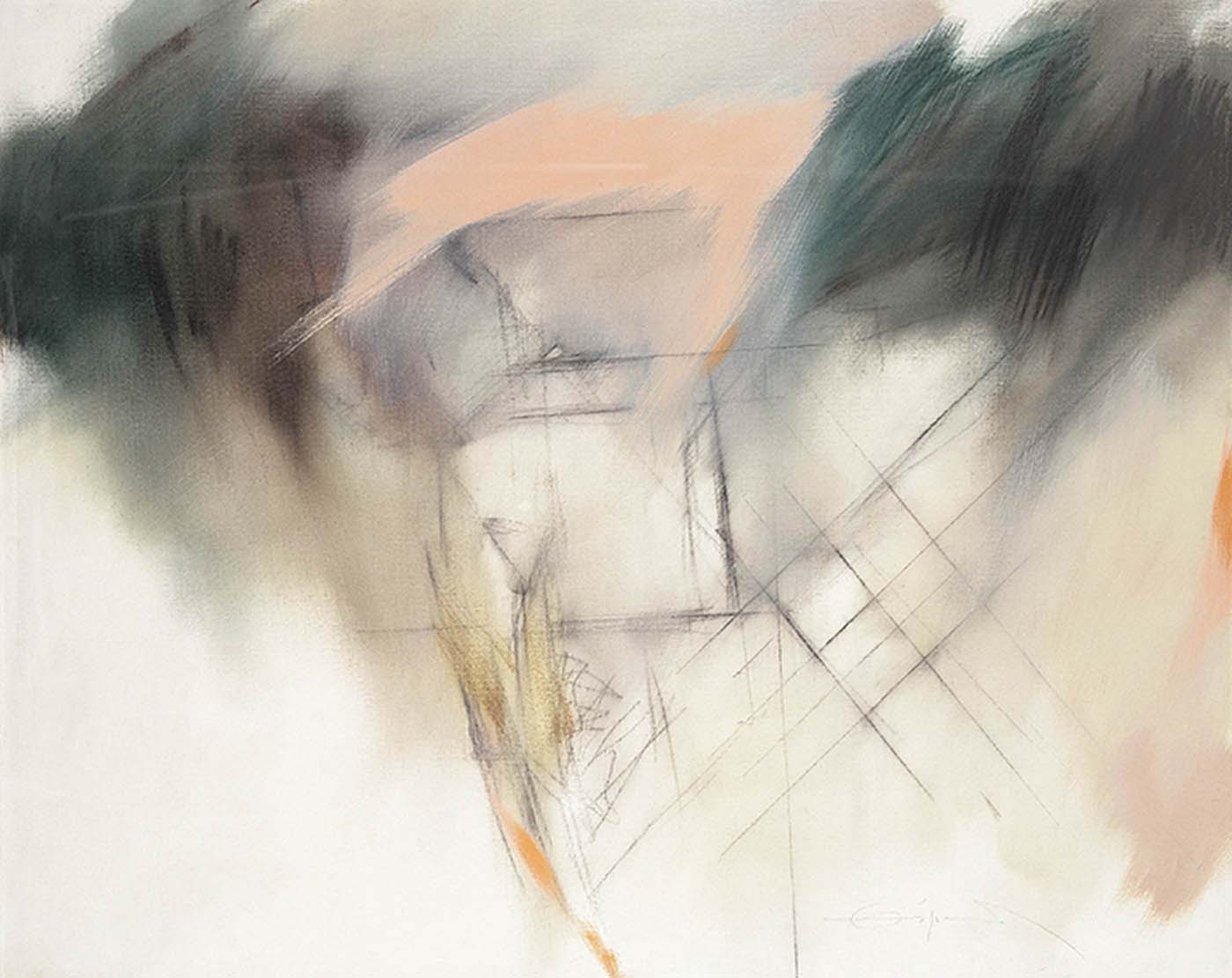

All his impulses as a painter coexisted, in a perfect balance, with that intellectual education and those activities that marked his personality and, above all, his style, his own way of doing things; a harmony between the idea, the realization and the results that sealed all his projects. His continuous search for order and balance was directly projected in his paintings.

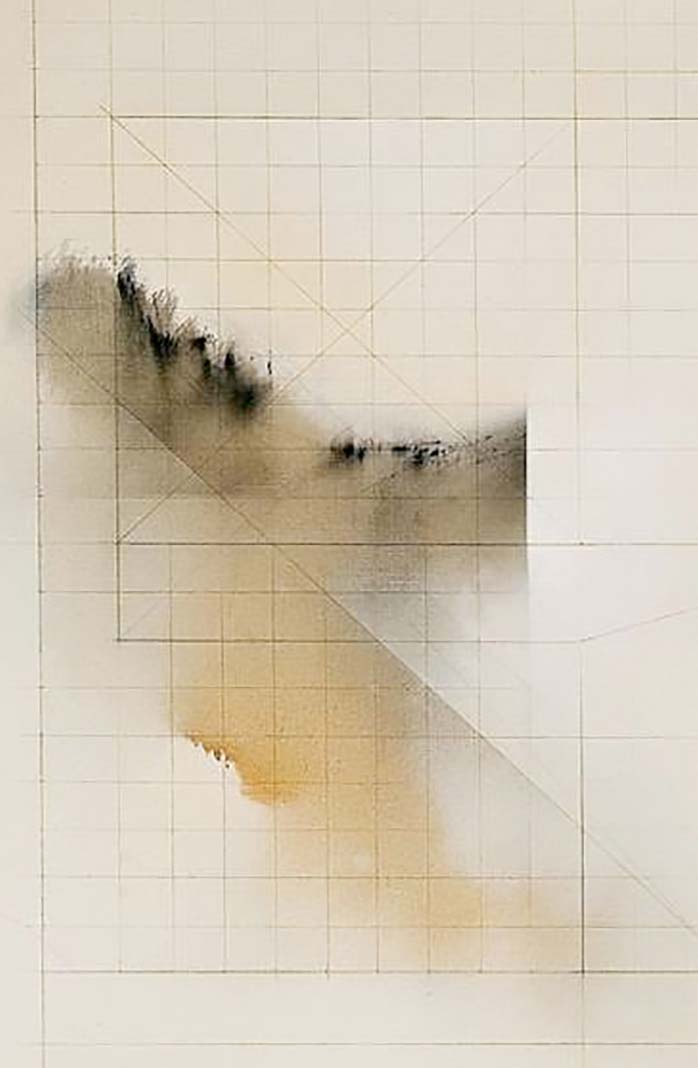

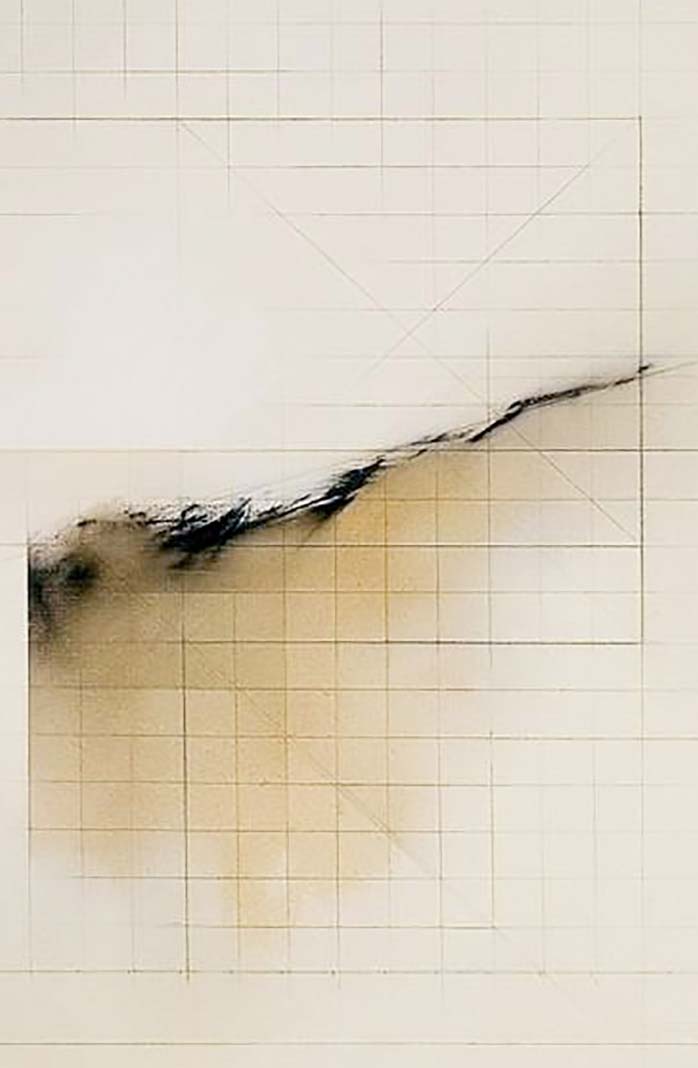

With all these antecedents, we find ourselves before an abstract painter, but with formal studies, a technique, procedures, and materials that make him conceive the work in a classical way:

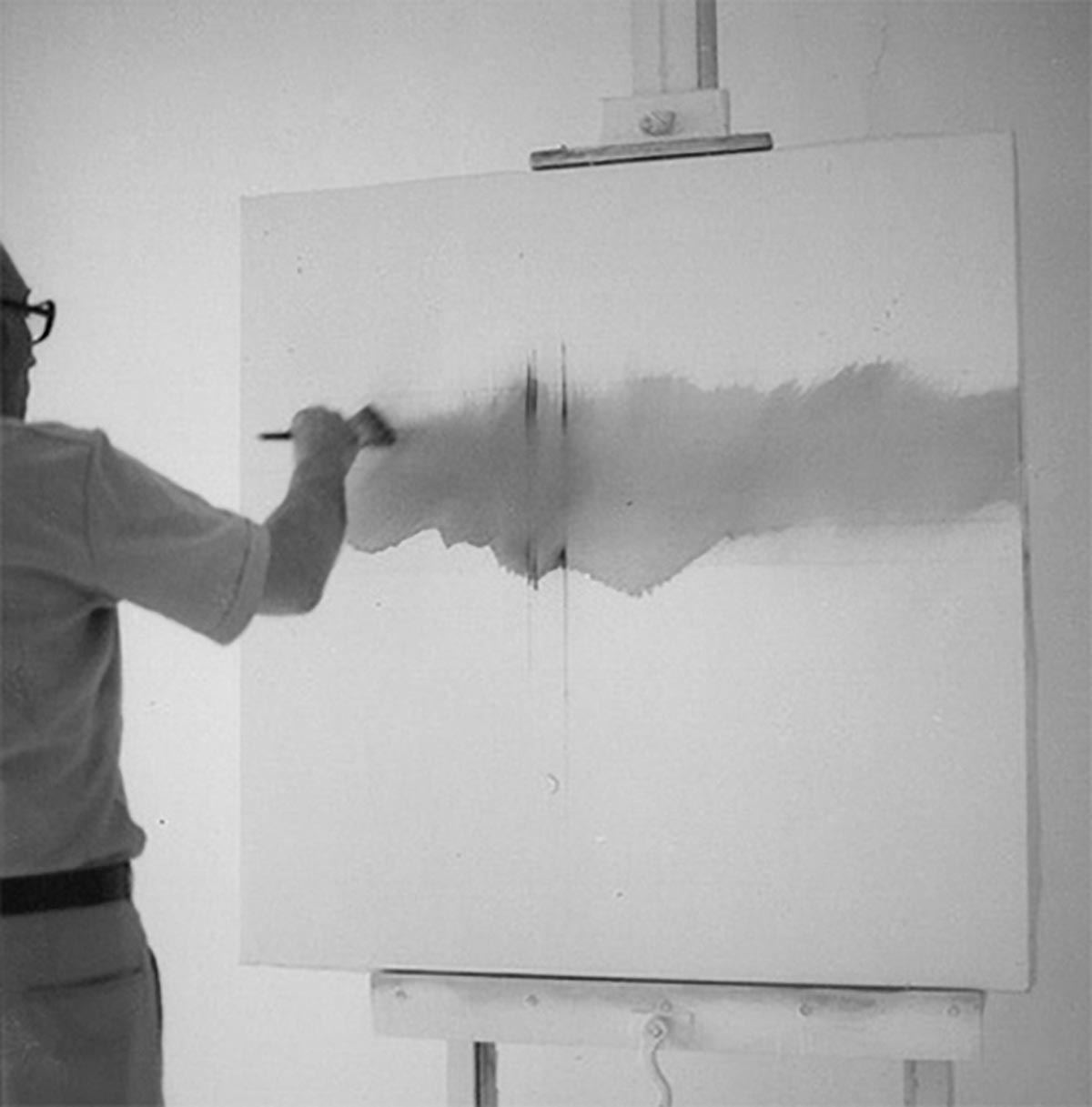

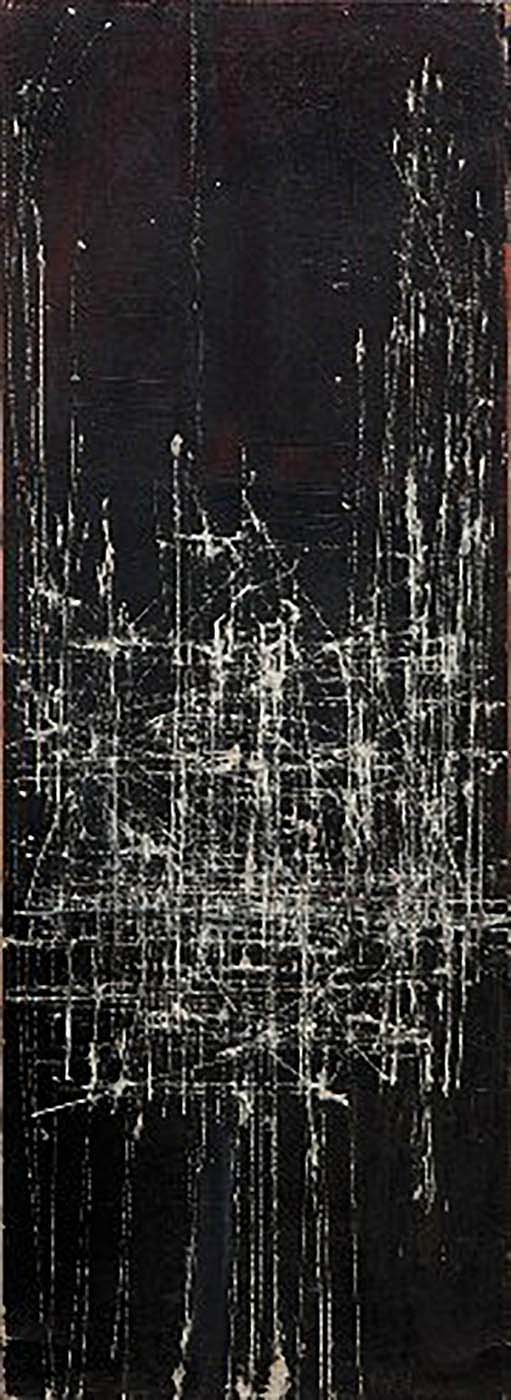

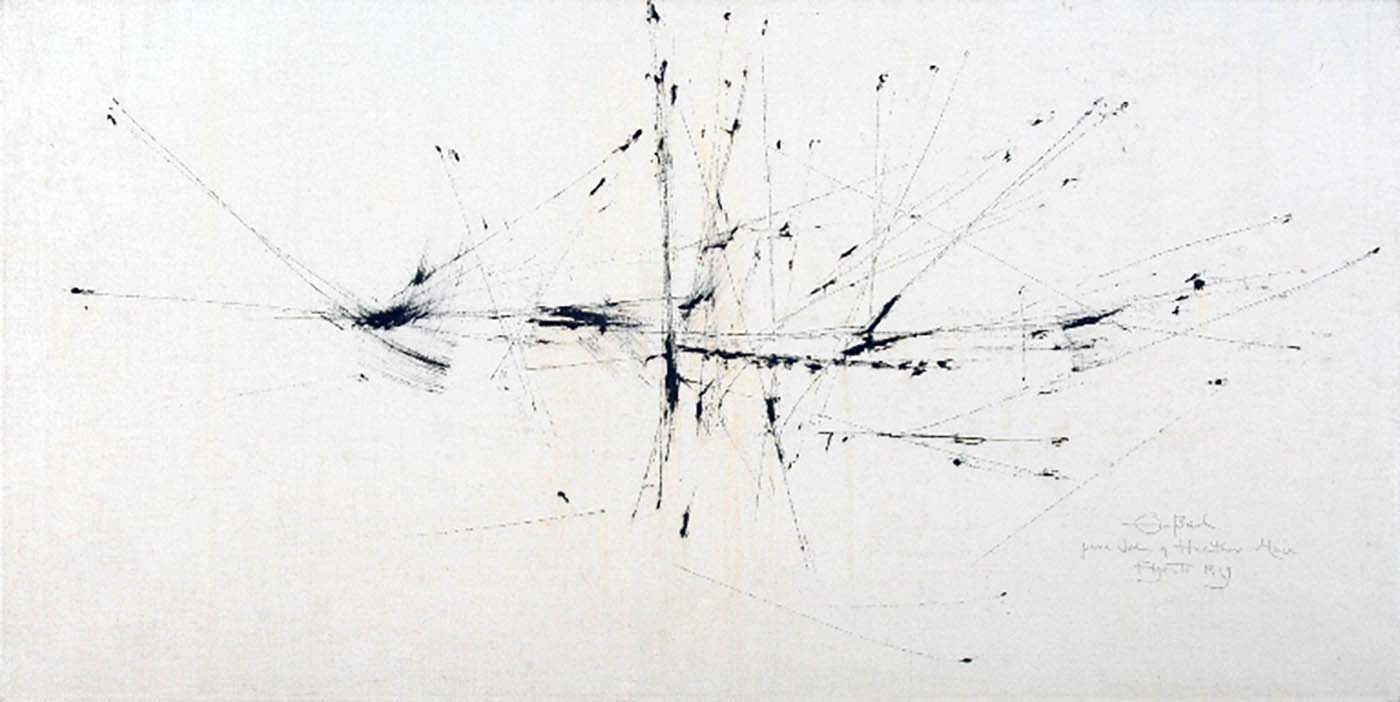

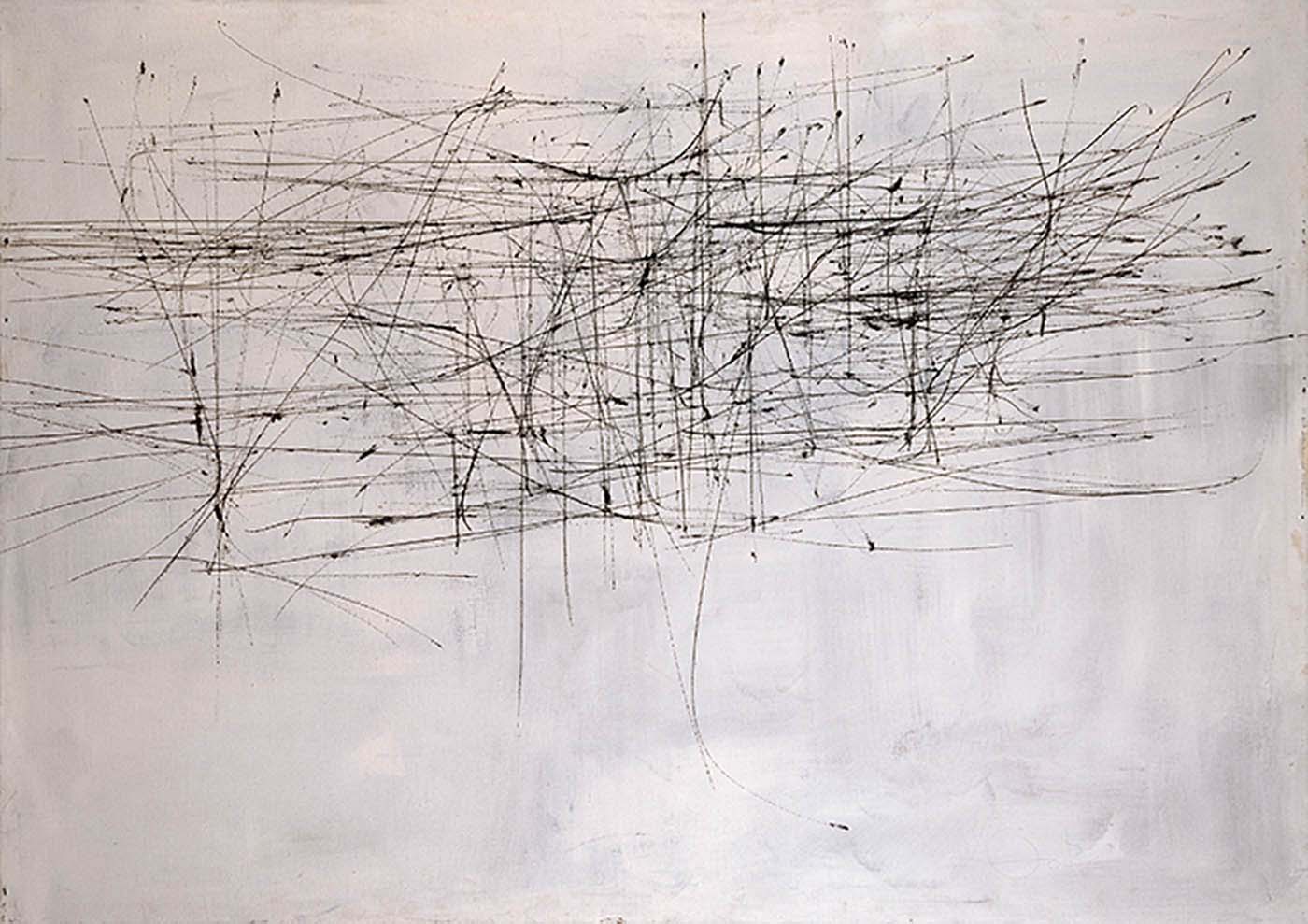

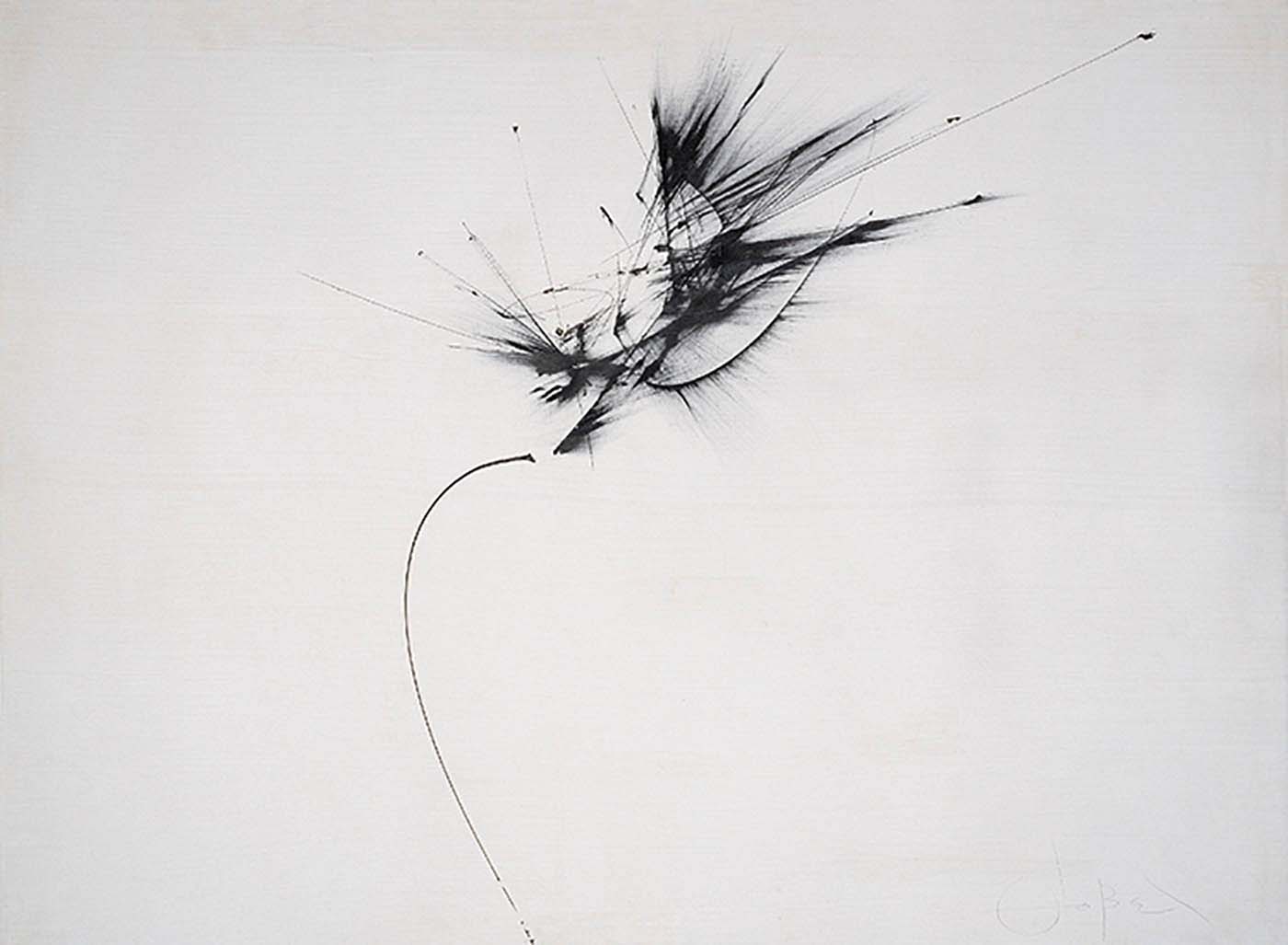

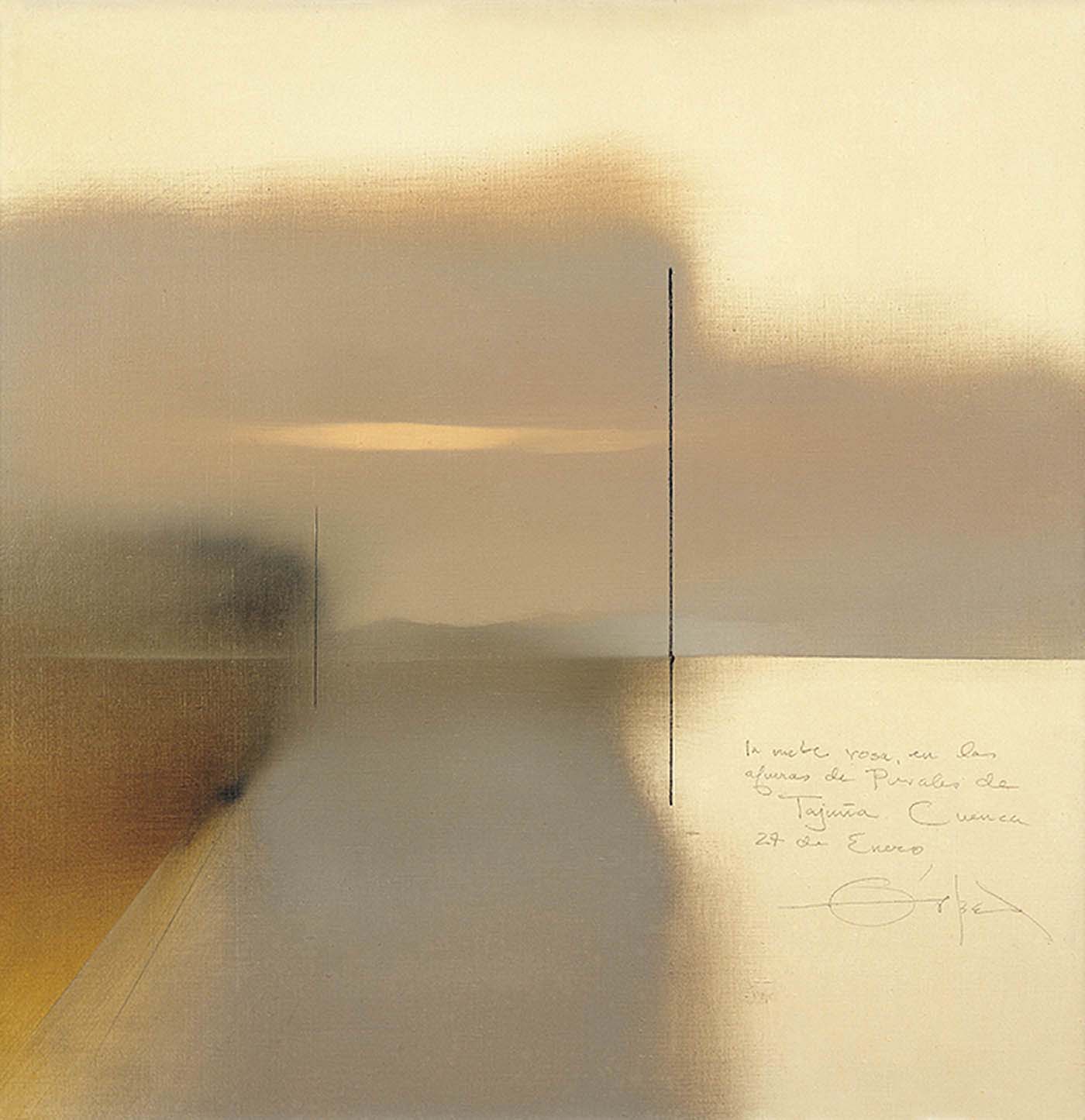

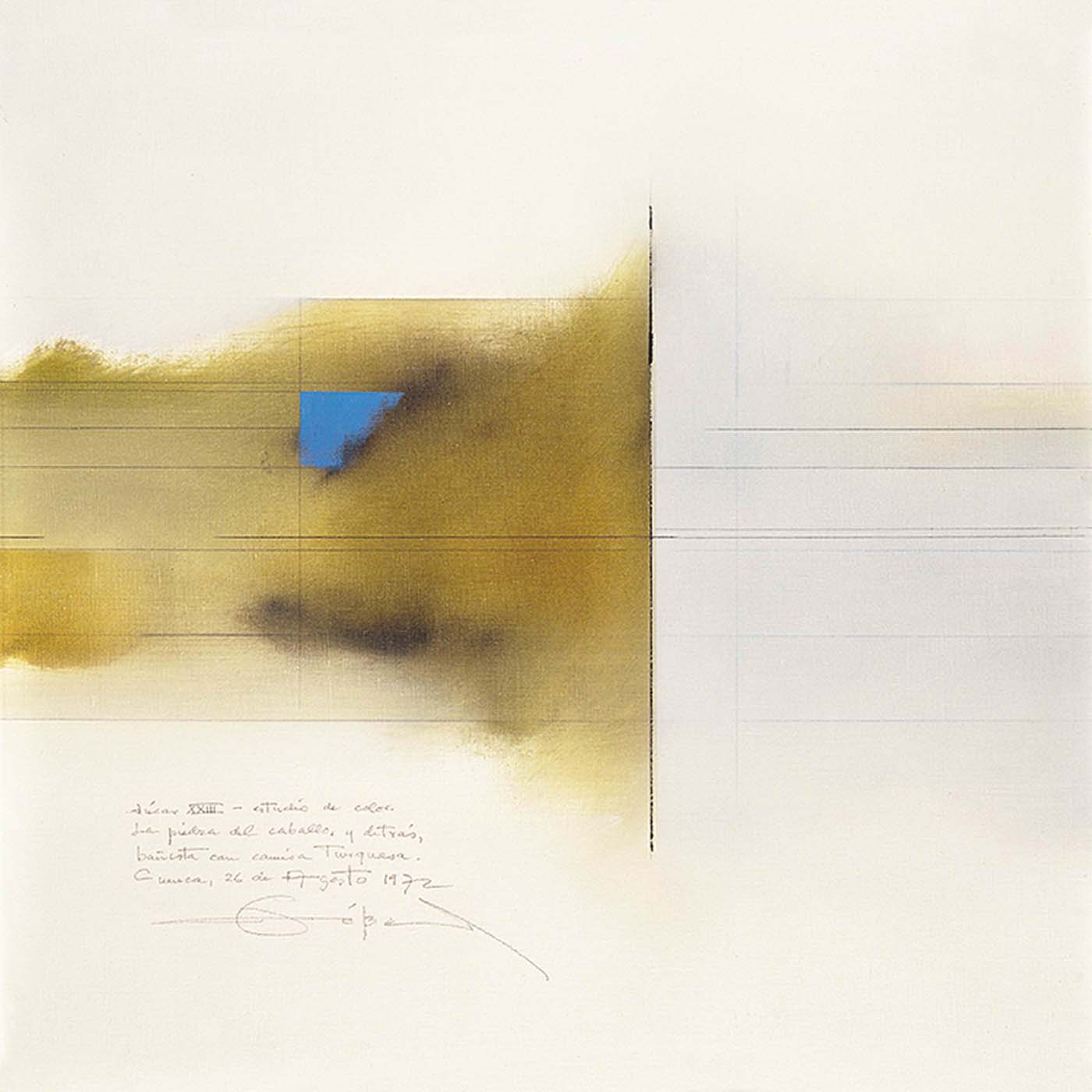

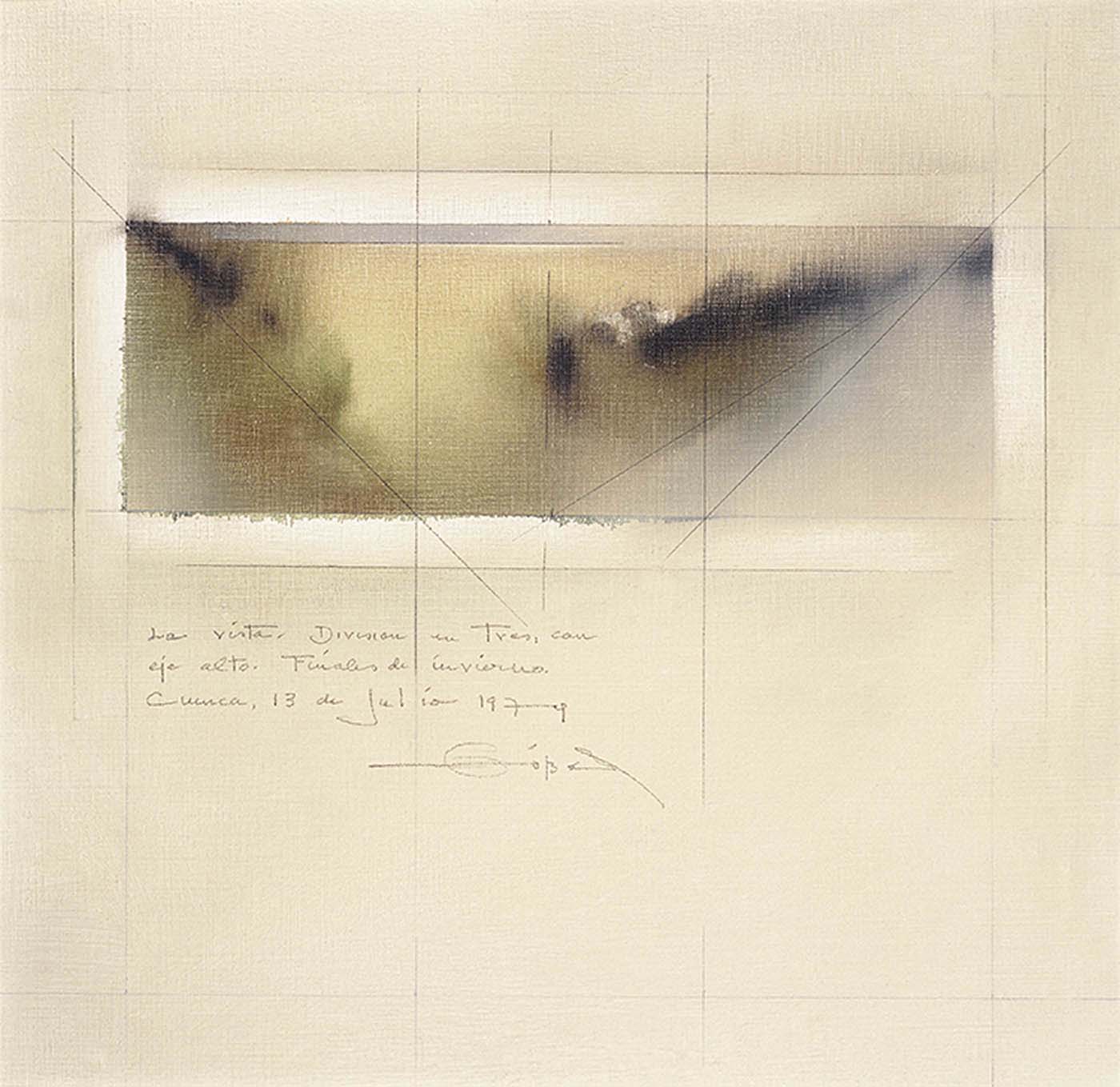

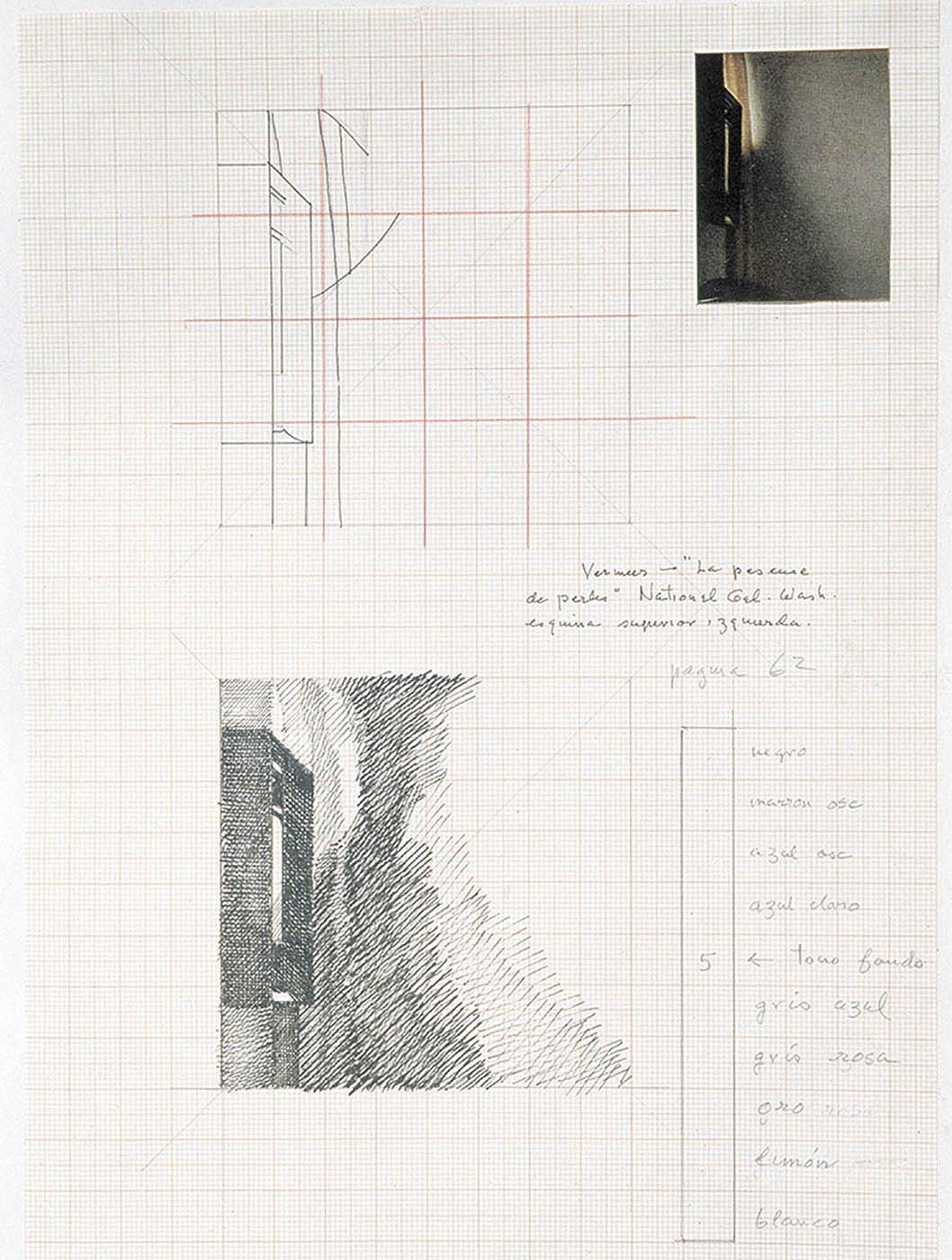

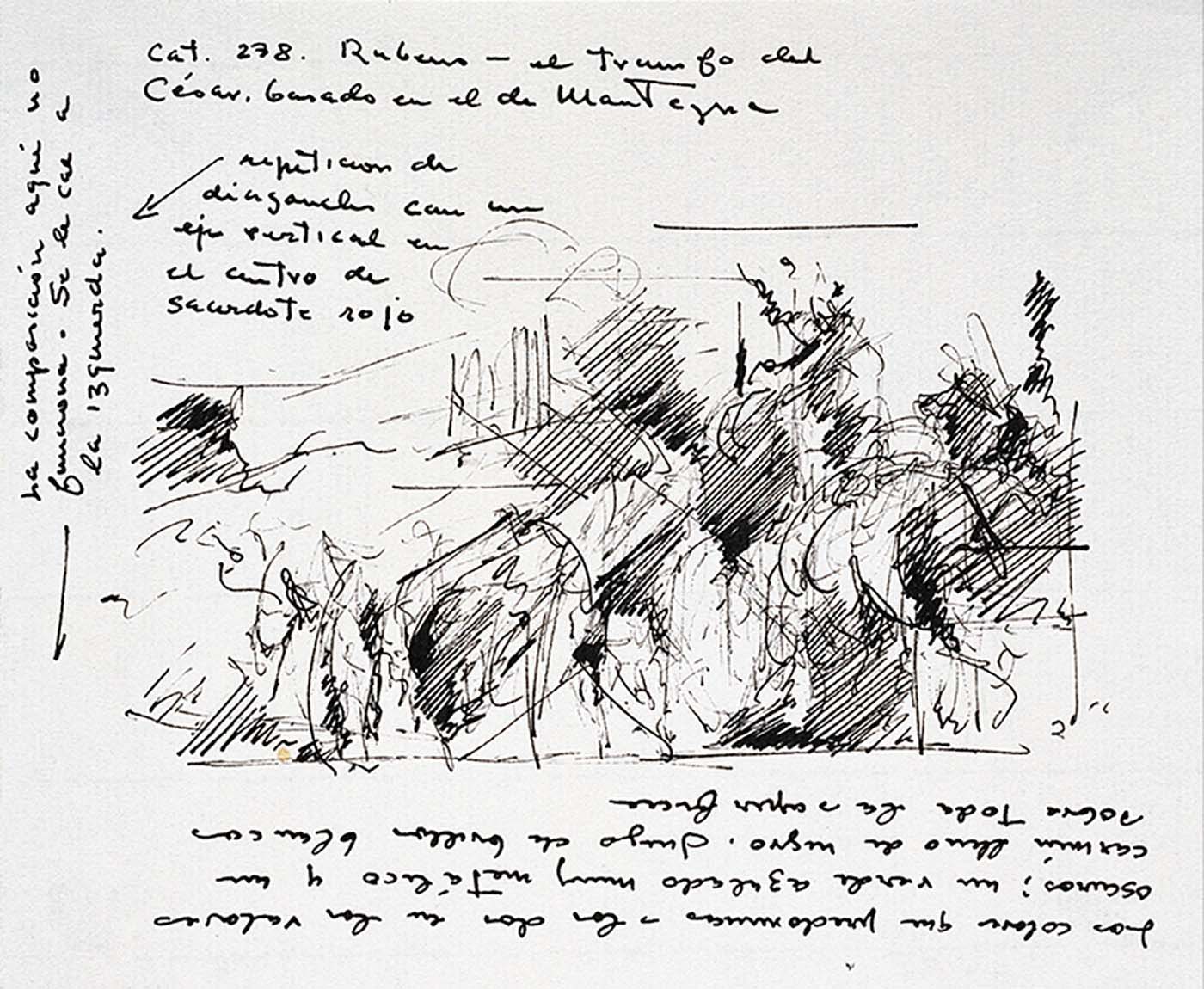

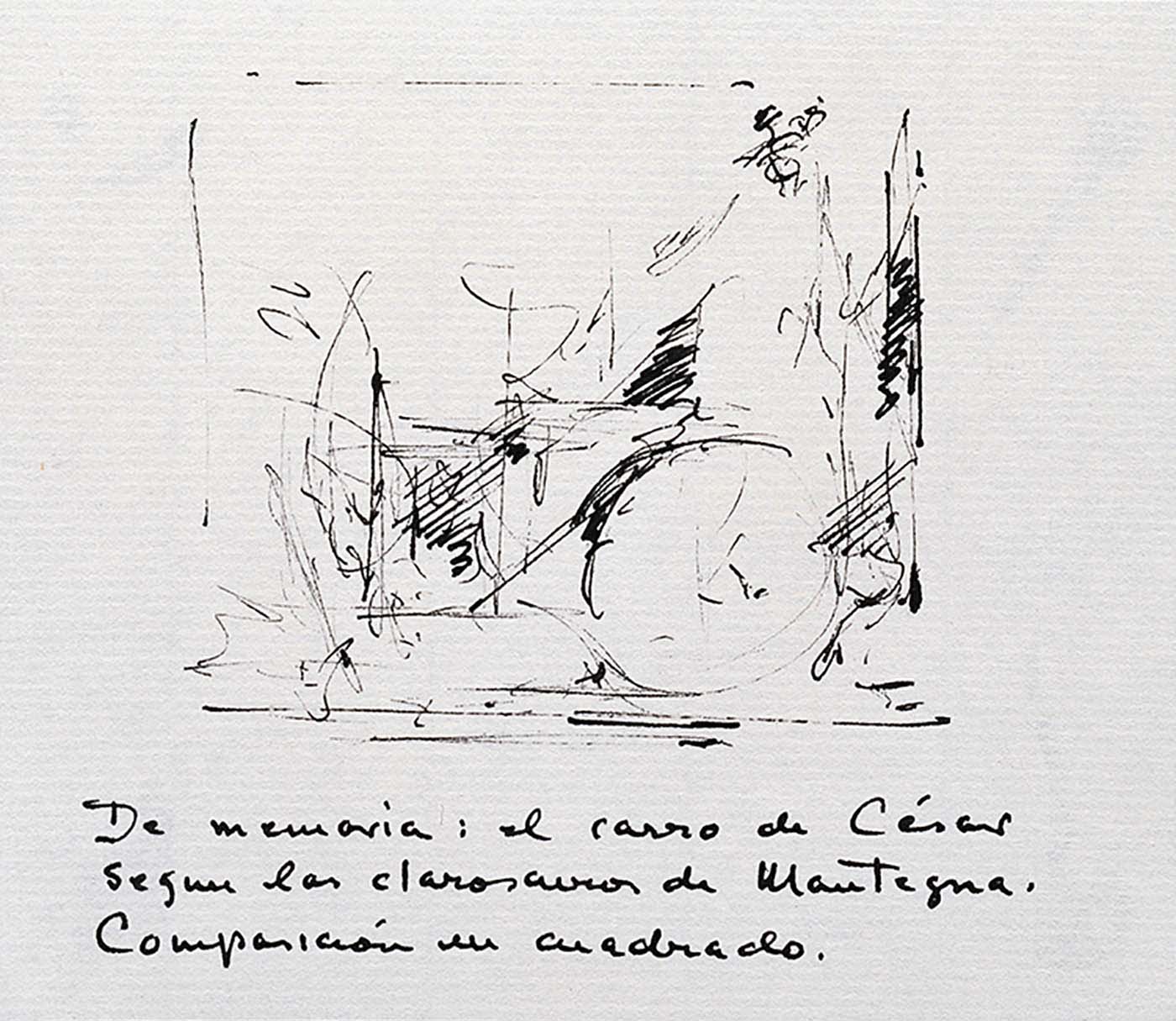

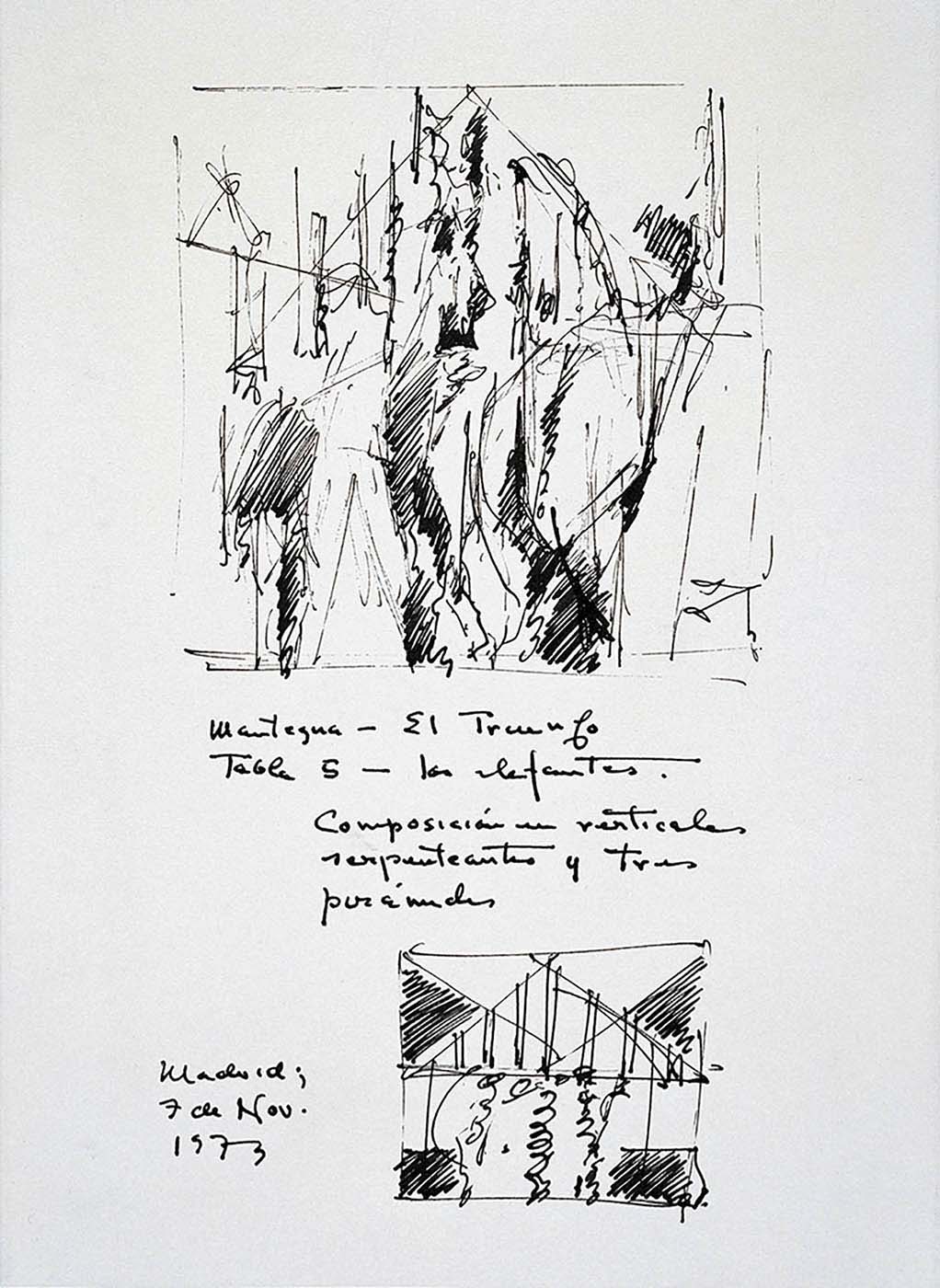

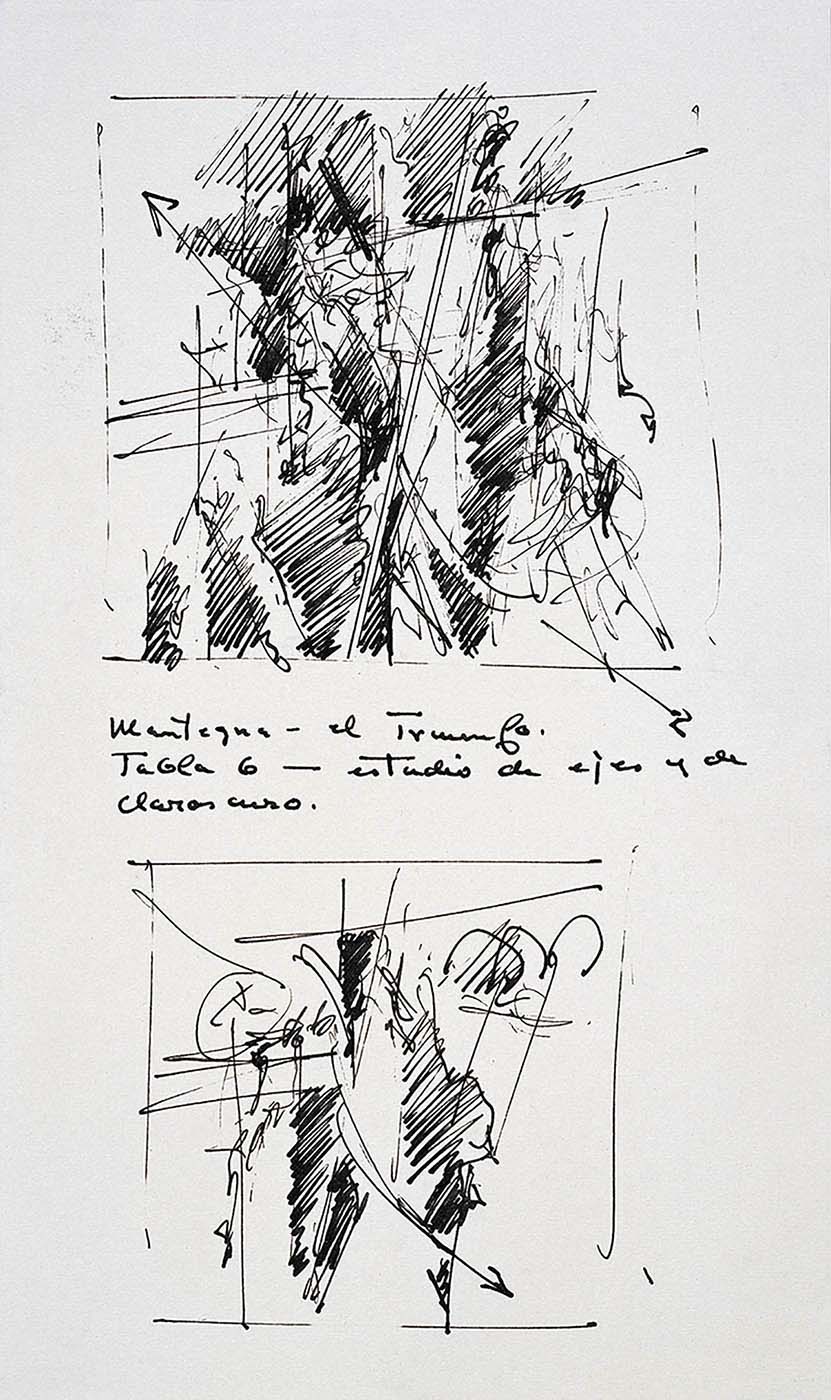

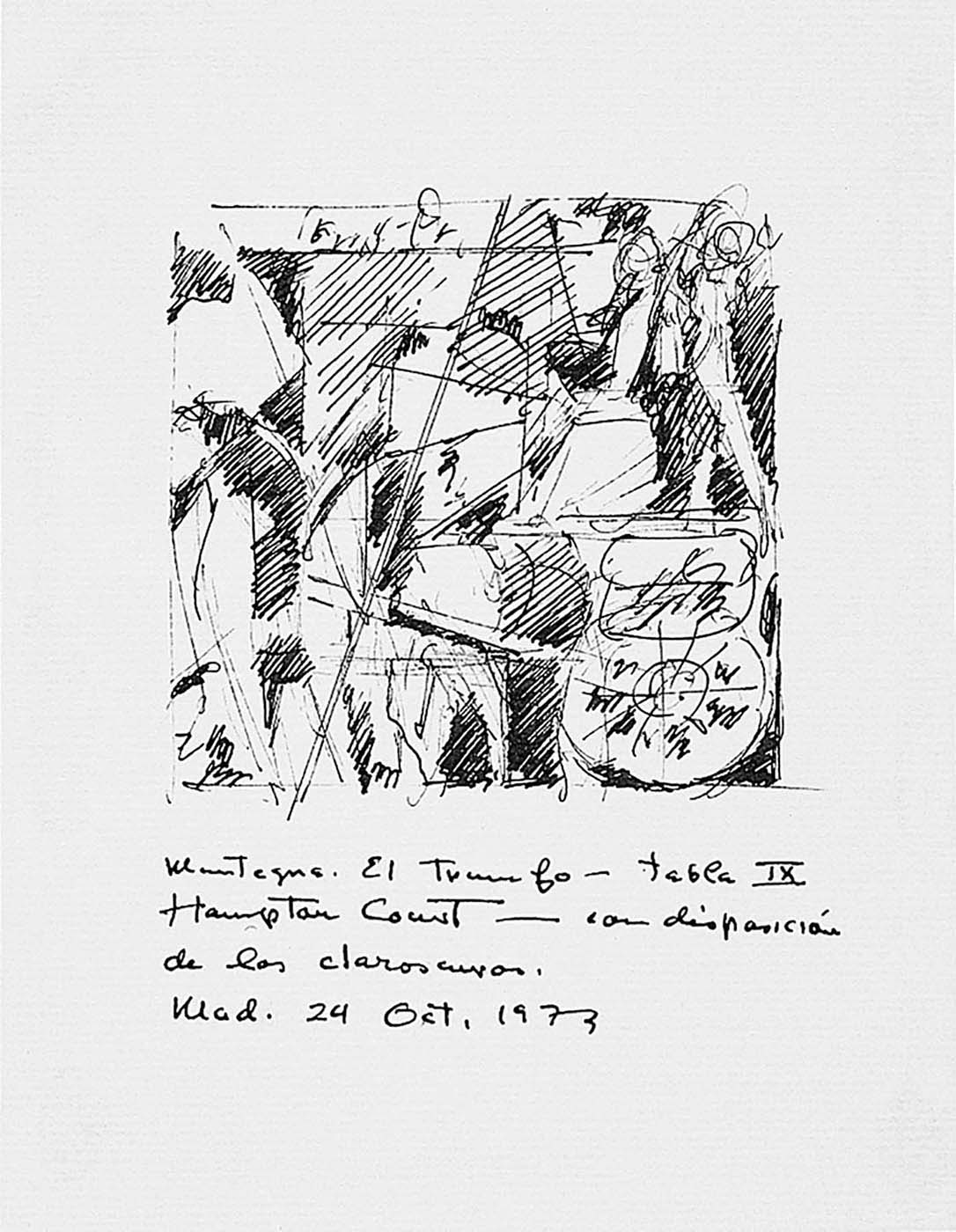

“My process is classic; it is the process of sketch-drawing-sketch-sketch-painting. The sketch tries to remember an idea. The drawing tries to fix it. The sketch is a rehearsal of realization. It is a process of elimination, of eliminating distractions. The painting aims to be the clearest possible realization of the initial idea” (1).

Francisco Calvo Serraller, in his text for the catalog of the exhibition "Zóbel", organized by the March Foundation, immediately after the painter's death, summarized it very clearly:

“This simple scheme of pictorial composition, which apparently only reflects the mechanical application of an academic workshop method, encloses, however, all the complex wisdom that transformed the plastic arts into a humanistic discipline”.

There is evidently a work of reflection, research and method.

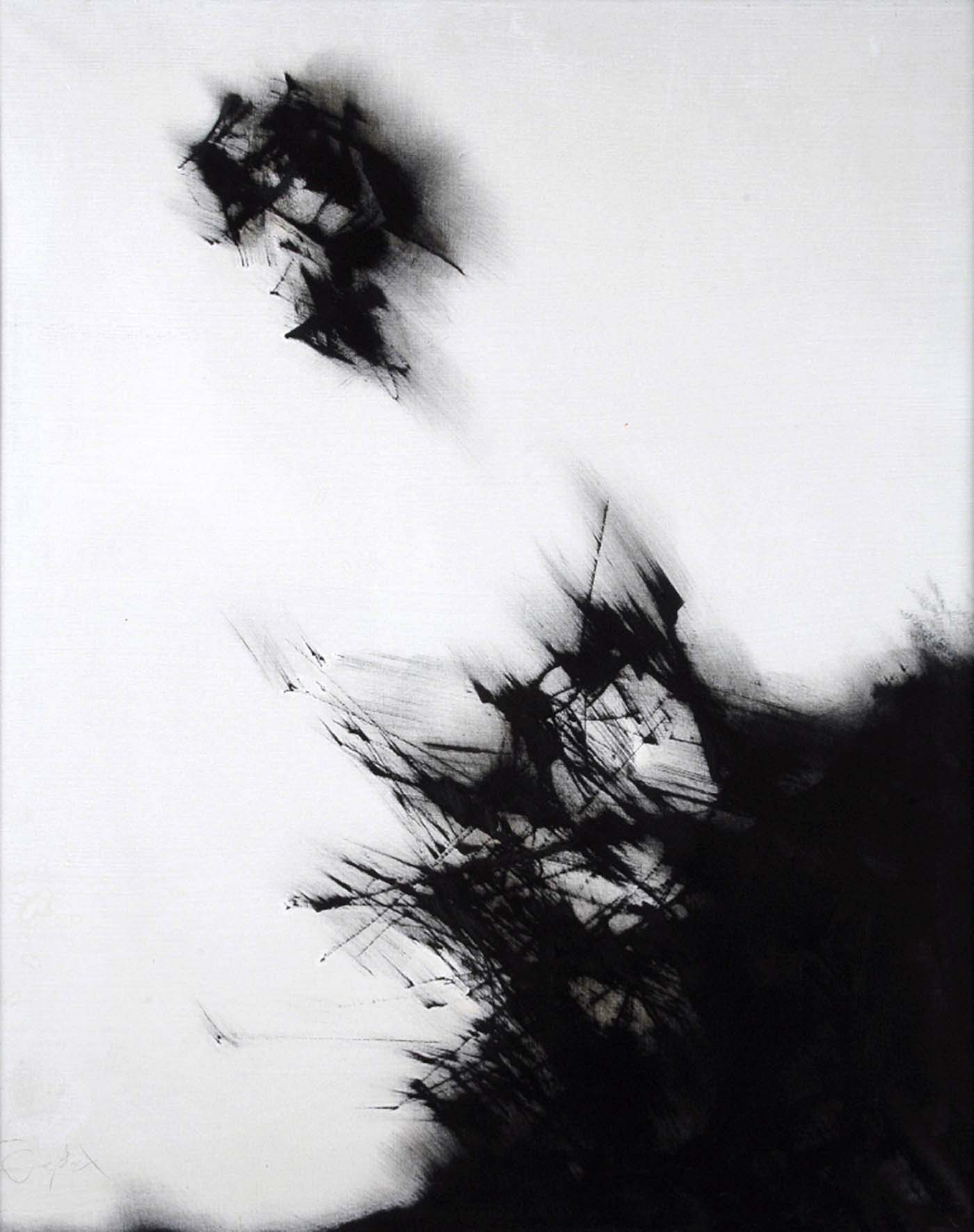

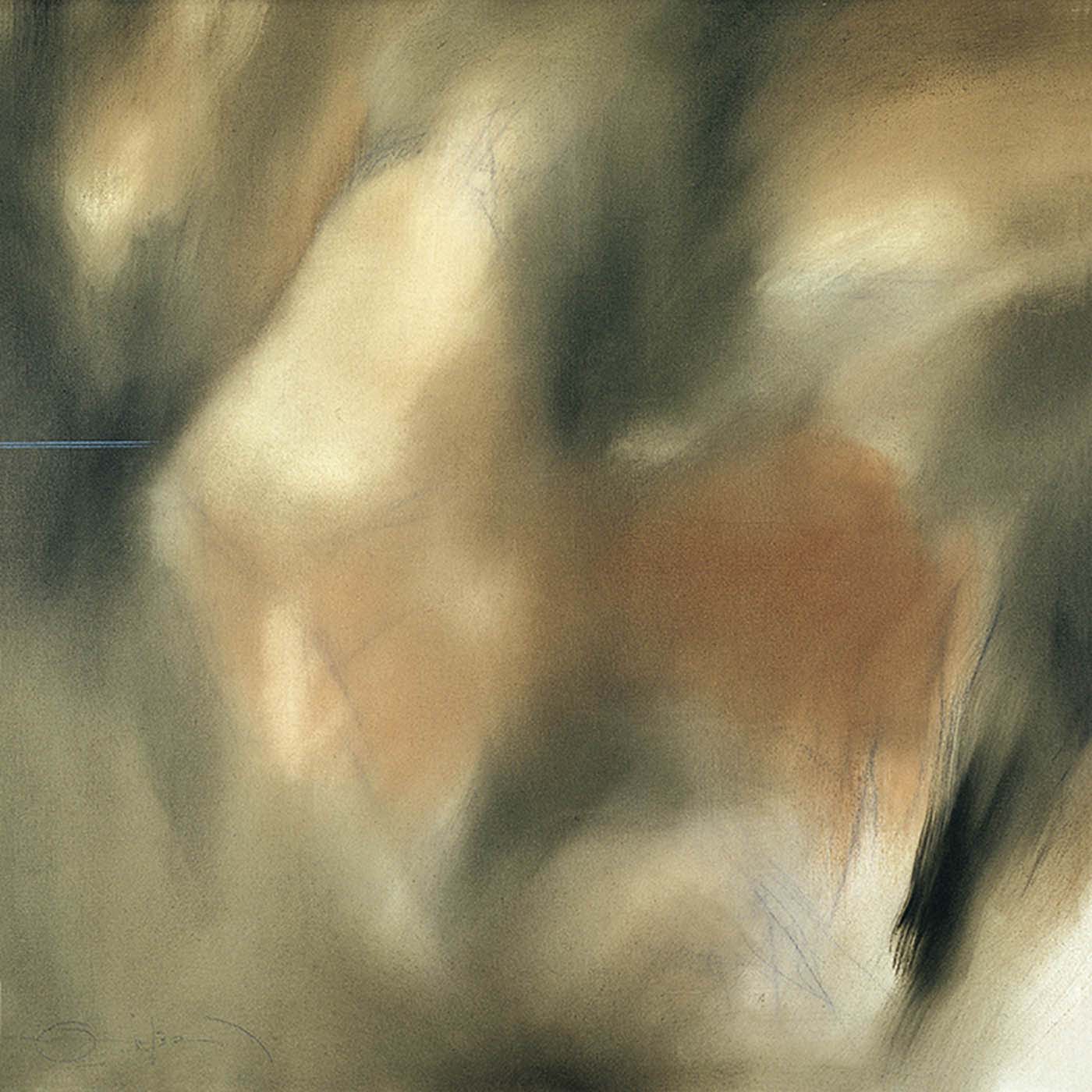

Naturally, and because of all this, it is also clear that Fernando Zóbel was a great draftsman, with a loose, fast stroke and an uncommon capacity for synthesis. His head was an authentic mental laboratory when it came to transforming the reality seen into that other reality of living and meaningful drawing.

The evocative and direct style of his painting does not let us see, sometimes, the intellectual elaboration work behind his work, but if we observe his drawings, we can see that there is nothing of improvisation or chance in his work. Everything is rehearsed, one and a thousand times, before reaching the canvas.